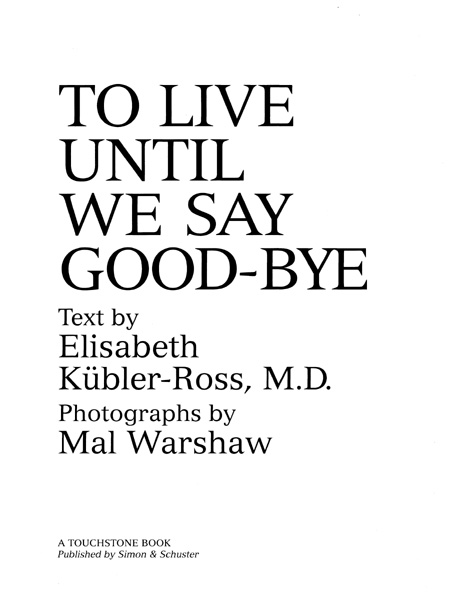

ELISABETH KBLER-ROSS IS THE AUTHOR OF

On Death and Dying

Questions and Answers on Death and Dying

Death: The Final Stage of Growth

To Live Until We Say Good-Bye

Living with Death and Dying

Working It Through

On Children and Death

AIDS: The Ultimate Challenge

The Wheel of Life

TOUCHSTONE

Simon & Schuster

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1978 by Ross Medical Associates, S.C., and Mal Warshaw

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

First Touchstone Edition 1997

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

eISBN: 978-1-4516-6447-8

The Library of Congress has cataloged a previous edition as follows:

Kbler-Ross, Elisabeth.

To live until we say good-bye.

1. DeathPsychological aspects. 2. Terminal care.

3. Terminal care facilities. 4. Future life.

I. Warshaw, Mal. II. Title.

BF789.D4K83 155.937 78-10301

ISBN 0-684-83948-2

CONTENTS

In addition to the patients in the bookwe thank:

Rev. Michael Stolpman, Hospice at Rogers Memorial Hospital, Milwaukee;

Sister Cecilia and Sister Mary David of St. Roses Home, New York;

Dennis Rezendes and John Abbott, Hospice, New Haven;

Lucy Kroll; The Staff of Shanti Nilaya; Robert Sussman Stewart,

Special Projects Editor, Prentice-Hall

PREFACEby Mal Warshaw

In a recent six-month period I lost four of the people closest to memy parents, a cousin and a best friendand almost lost my wifes mother who hovered between life and death for many months. These events, coming as they did within such an incredibly short period, profoundly affected me and intensified the experience of encountering the end of life.

When Richard Bove, a colleague at Pratt Institute, where I was teaching, suggested during that period that death should be the subject of a photographic book, I was immediately drawn to the idea. My wife, Betty, caught the excitement and saw the value of trying to capture visually the various aspects of the process of dying. It was her encouragement, her intellect, and most important, her generosity in allowing me to share with her her own terror, fears, and fantasies about dying that opened up in me my own deeply buried feelings and started a process of investigation in order to seek answers to our common anxieties about death.

My friend and agent, Lucy Kroll, introduced me to Beth, a vital woman just 42 years old, who was dying of cancer and was willing to share that experience and permit me to photograph the terminal phase of her life.

After I was well into working with Beth and had taken hundreds of photographs of her, a friend suggested that I show them to his friend Elisabeth Kbler-Ross. Dr. Kbler-Ross and I met and talked, and out of that encounter grew an agreement to work together, as well as a friendship, mutual admiration, and respect. Knowing Dr. Kbler-Ross with her special insights and qualities has been one of the most important gifts this collaboration has brought me.

Working with Beth and having recently observed my friends and family in a similar situation, I noted that the faces of people who have a terminal disease, and who have come to terms with their own impending death, have a look that is a marvelous combination of tranquility and incredible power and insight. What I hoped to do was to capture the essence of that look in a photograph, so that those feelings could be broadly shared. And it was evident at the outset that a series of photographs would be necessary to show something of the process and to provide a frame of reference for each individual history.

Usually a photographer enjoys a unique, meaningful relationship with his subject, whether the subject is human, a scene in nature, or an inanimate object. He is an observer, detached from the scene, objectivewith a visceral sense of the aesthetics in any given situation. He develops what social workers call a therapeutic stance which allows his artistry, professionalism, and expertise to function at maximum levels. Under most circumstances this works.

Any distancing from the subjects in this work, however, was unthinkable. Happily for me (and I hope my work) my subjects became my friends. There is no way to remain the slightest bit aloof from a dying friend if you want to keep the channels of communication open and share the experience.

A major challenge in making the photographs for this book was dealing with the unknown. There is no way to predict the exact second when something dramatic or something filled with intense meaning is going to happen. I wanted to be there, standing in the right place, with the right lens, to capture what Robert Frank called the humanity of the moment. To prearrange this was obviously impossible. A large part of the technique I developed was to invest the time, to be available, to know, to understand, and to be a part of what was happening, to be guided by my instincts, and to let my sense of human connection serve as a focal point.

The luxury of working this way was made possible by the present state of the art of photography. I worked with existing light, used no special lights or popping flashes, so that the camera would intrude as little as possible. All the photographs were taken with 35mm single-reflex cameras. The availability of fast film plus a variety of fast lenses greatly increased my ability to adapt to a great variety of ever changing environments.

There are no posed pictures in this book. I asked my friends to permit me to be present (in the background with my camera) as an observer of the small, incidental events of daily life, as well as, of course, of the special times.

My subjects became very important in my life. They were my teachers. They were making me examine myself in ways I had previously avoided. It was painful, yet strangely reassuring. I found that as I permitted myself to confront the fact of dying, I was more fully embracing life. I felt lighter and more at ease with myself.

I shall always be grateful to our friends for welcoming us into their lives: to Beth, to Louise, to Linda and Jamie, to Jack, and to all the terminal patients for sharing their most precious possessionthe short time they had left.

I have tried to record in photographs the various developments in the process of dying, the visual images of the inner struggle to accept the inevitability of death.

I hope that as you read and look at what follows, you too will become more comfortable with the idea of dying and be able to live, as I now do, more freely.

INTRODUCTION

by Elisabeth Kbler-Ross

I first met Mal Warshaw through a mutual friend who was familiar with my work with terminally ill patients and with Mals search to understand better the mystery of death. After an initial conversation with Mal, during which he shared his interests with me, I invited him to come to my house, where I had an opportunity not only to meet Mal the photographer, but Mal the person, who, like so many other people, cared enough to become involved in a field that too many people try to avoid.

It was clear that Mal, like so many others in our society, was not at peace with the issue of death. But he had one great advantage, and that was the willingness to look at his own fear, guilt, and unfinished business, and try to find answers to the many questions he had, not only about the issue of death and dying, but about life and living itself and the care we give to those who have to face their own finiteness.

Next page