To the memory of

M Y F ATHER

and of

S EPPLI B UCHER

Acknowledgments

There are too many people who have directly or indirectly contributed to this work to express my appreciation to them individually. Dr. Sydney Margolin deserves the credit for having stimulated the idea of interviewing terminally ill patients in the presence of students as a meaningful learning-teaching model.

The Department of Psychiatry at the University of Chicago Billings Hospital has supplied the environment and facilities to make such a seminar technically possible.

Chaplains Herman Cook and Carl Nighswonger have been helpful and stimulating co-interviewers, who also have assisted in the search for patients at a time when that was immensely difficult. Wayne Rydberg and the original four students by their interest and curiosity have enabled me to overcome the initial difficulties. I was also assisted by the support of the Chicago Theological Seminary staff. Reverend Renford Gaines and his wife Harriet have spent countless hours reviewing the manuscript and have maintained my faith in the worth of this kind of undertaking. Dr. C. Knight Aldrich has supported this work over the past three years.

Dr. Edgar Draper and Jane Kennedy reviewed part of the manuscript. Bonita McDaniel, Janet Reshkin, and Joyce Carlson deserve thanks for the typing of the chapters.

My thanks to the many patients and their families is perhaps best expressed by the publication of their communications.

There are many authors who have inspired this work, and thanks should be given finally to all those who have given thought and attention to the terminally ill.

Thanks is given to Mr. Peter Nevraumont for suggesting the writing of this book as well as to Mr. Clement Alexandre, of the Macmillan Company, for his patience and understanding while the book was in preparation.

Last but not least I wish to thank my husband and my children for their patience and continued support which enables me to carry on a full-time job in addition to being a wife and mother.

Contents

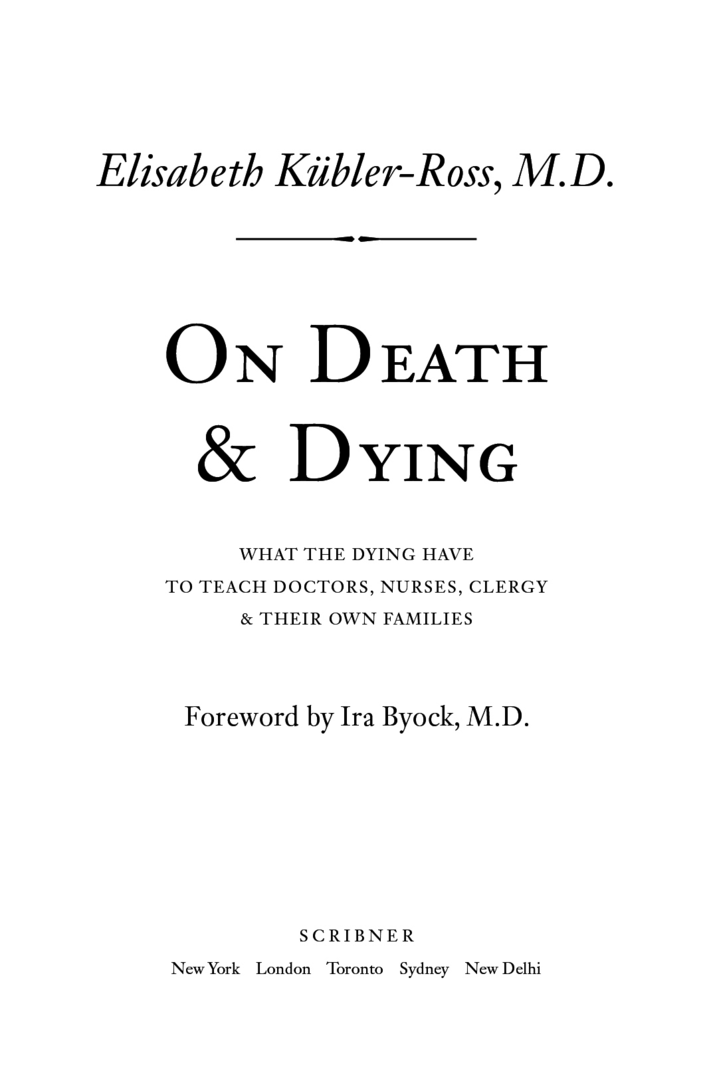

Foreword to the Anniversary Edition

In the postWorld War II era, as with every other aspect of social life, optimism and defiance pervaded Americas orientation to illness. Having endured the Great Depression, two world wars, and the Korean War, invincibility and perseverance were parts of the can-do American persona. A hopeful attitude in the face of adversity seemed intrinsically virtuous, part of the American way.

And there were good reasons to be optimistic. Startling breakthroughs in physics, chemistry, engineering, andto most people most importantmedicine were occurring almost daily. Cures for hitherto lethal conditions such as pneumonia, sepsis, kidney failure, and severe trauma had become commonplace. Disease was increasingly seen as a problem to be solved. The sense was that medical science might soon be able to arrest aging and (subconsciously at least) possibly conquer death itself.

In this culture, the best doctors were the ones who could always find another treatment to forestall death. In the 1950s and 1960s doctors rarely admitted when treatments werent working and commonly failed to tell patients when further treatments would do more harm than good. Physician culture epitomized the never-say-die stance, but doctors were not the only ones to maintain this pretense: sick people and their families all too readily colluded to avoid talking about dying.

It was common at the time for doctors to woefully undertreat seriously ill patients pain to the (often needlessly) bitter end. This was only partly due to the fact that doctors were poorly trained in the management of pain and other symptoms. It was also due to the conspiratorial, sunny pretense that doctors, patients, and their families maintained. Admitting that a persons pain was getting worse might mean admitting that his or her disease was getting worse.

The medical culture of the era was highly authoritarian. A patients values, preferences, and priorities carried little weight. Doctors informed patients of the decisions they had made and patients accepted those decisions. In addition to the death-defying prowess and prestige that distinguished the most successful doctors, peer pressure contributed to widespread neglect of peoples pain. While during the last hours of life most doctors would give enough morphine to keep patients from dying in agony, fears of raising eyebrows among colleagues kept many from giving their dying patients enough medication to be as comfortable as possible for the months they had left to live.

Elisabeth Kbler-Rosss On Death and Dying challenged the authoritarian decorum and puritanism of the day. In a period in which medical professionals spoke of advanced illness only in euphemisms or oblique whispered comments, here was a doctor who actually talked with people about their illness and, more radically still, carefully listened to what they had to say.

Kbler-Ross and this book captured the nations attention and reverberated through the medical and general cultures. The very act of listening delivered illness and dying from the realm of disease and the restricted province of doctors to the realm of lived experience and the personal domain of individuals. When I first read On Death and Dying as a college student aiming toward a career in medicine, I was struck by the interview transcripts that revealed the respect that was evident in Kbler-Rosss listening and her unpretentious friendliness toward patients.

On Death and Dying sparked changes to prevailing assumptions and expectations that transformed clinical practice within very few years. In reasserting peoples personal sovereignty over illness and dying, Kbler-Rosss book brought about a radical restructuring of patients relationships with their doctors and other clinicians. Suddenly, how people died mattered. No longer were dying patients relegated to hospital rooms at the far end of the hall. On Death and Dying is rightly credited with giving rise to the hospice movementand, by extension, the new specialty of hospice and palliative medicinebut the changes it set in place have pervaded nearly every specialty of medicine and nursing practice. For instance, by the late 1990s pain would become a fifth vital sign to be assessed in hospitals every time a patients temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respirations were measured.

On Death and Dying also had profound impact on human research. No longer could experiences of the dying be objectified, nor could the study of dying be relegated to component histological, biochemical, physiological, or psychological pathologies. Instead, Elisabeth Kbler-Rosss groundbreaking work opened up entirely new fields of inquiry into the care and subjective experiences of seriously ill people. The resulting interest in and validity of both quantitative and qualitative research on dying and end-of-life care accelerated advances within psychology and psychiatry, geriatrics, palliative medicine, clinical ethics, and anthropology.

Although she was steeped in the psychiatric theory of her day and proud of it, Elisabeth Kbler-Ross was not bound by Freudian or Jungian formulations to her patients experiences. Instead she let the voices and perspectives of the people she interviewed predominate. Her interviews allowed people to explain in their own words how they struggled to live with and make sense of an incurable condition. The psychodynamics that most interested Kbler-Ross were those between the person who was now incurably ill and the person who until now had been well.