First Mariner Books edition 2019

Copyright 2018 by Ben Fritz

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Title: The big picture : the fight for the future of movies / Ben Fritz.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018. | An Eamon Dolan Book. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046230 (print) | LCCN 2018010456 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544789777 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544789760 (hardcover) |ISBN 9781328592743 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picture industryCaliforniaLosAngelesHistory21st century. | Motion picturesUnitedStatesHistory21st century. | Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc.

Classification: LCC PN 1993.5. U 65 (ebook) | LCC PN 1993.5. U 65 F 75 2018 (print) | DDC 384/.80973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046230

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

Cover photograph Danita Delimont / Getty Images

Author photograph Charlie Chu

v2.0119

In memory of Riley

A Note on Sources

THIS BOOK IS BASED , in part, on stolen material. I wont make any bones about it.

The cyber-breach of Sony Pictures Entertainment in November 2014 resulted in the release of tens of thousands of private e-mails and documents, which became available to the public, whether downloaded from a peer-to-peer network or perused on WikiLeaks.

Sony has called the hack a malicious criminal act, and thats correct. Executives at the studio have questioned my ethics (and that of many other journalists) in reporting on the contents of the stolen e-mails and documents, and I can hardly blame them. If e-mails revealing the innermost details of my reporting at the Wall Street Journal were released to the world, I would be horrified. And if bloggers burrowed through personal e-mails involving my family, my finances, and my online shopping history, I would undoubtedly be embarrassed.

Nevertheless, its an undeniable fact that much great journalism has used stolen material as its source. While the scale of the theft here was perhaps unprecedented and the import of the material doesnt exactly compare to the Pentagon Papers, the principle remains the same: interesting information worthy of public scrutiny is fair game for journalists.

Now that anyone with an Internet connection can read these e-mails and documents, the question is simply what to do with them. Already, reporters have pored over many, looking for eyebrow-raising scoops, including new details about movies Sony was planning to make and racially offensive jokes about President Obama made by a movie mogul and a power producer.

Of course, I could have just left the hacked materials alone and moved on. Thats possibly what some Sony Pictures employees, for whom the hack was a painful incident theyd like to just leave in the past, would prefer I do. But as a longtime reporter on the business of Hollywood, I believed the stolen e-mails and internal documents from Sony Pictures could be the core of a much bigger storyone about the changes in Hollywood and why we get the movies we do. I believed I could put these materials to a productive and enlightening purpose. This book is the result.

Whatever your views, I hope youll agree that what youre about to read is not exploitative. In researching this book I read or skimmed nearly every e-mail and document released in the hack. I frequently felt uncomfortable, as I think any compassionate human being would, and at times I felt unethical. That happened when I came upon e-mails of a clearly personal nature, particularly when it involved Sony employees families and doubly so their children. I made it a policy to stop reading e-mails once I realized they were personal. You wont find anything salacious or shocking about anyones private life in here.

There are, however, extensive details, financial and otherwise, about Sony Pictures, its films, and its senior executives. Much of it comes from e-mails and documents stolen in the hack. Some comes from interviews with more than fifty current and former Sony employees and people who have worked closely with the company. I also utilized internal documents not released in the hack that sources provided to me.

Wherever possible, I have cited the specific e-mails or people I interviewed from which I gleaned quotes or information used in this book. Unless otherwise noted, I have preserved the original spelling and wording of e-mails I quote, including typos.

Some financial data came from internal documents that have no titles, so I cant individually cite them. In addition, I granted anonymity to some people I interviewed because they feared that being named would damage their careers in Hollywood.

Introduction

Groundhog DayHow Franchises Killed Originality in Hollywood

Its easy to become cynical about Hollywood once youve spent much time inside it. No business is as sexy and highly scrutinized from the outside, while managing to feel so small and self-important once youre inside it, as motion pictures.

When everyone around you is constantly assessing the current heat of stars, moguls, and filmmakers and judging movies by their most recent box-office grosses, its easy to forget that the products created here are profoundly meaningful to millions of people, whether as timeless art or fun pop-culture ephemera.

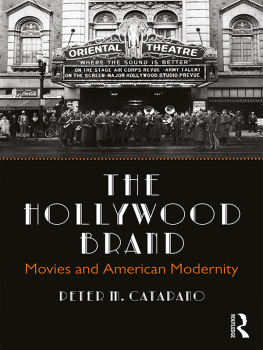

Theres an antidote, however. To remember the grandeur, the tradition, and the cultural significance of an industry that has had a greater impact on imaginations than any in American history, one need only walk onto one of the six studio lots that still take up hundreds of acres in Los Angeles and its suburbs.

None is more inspiring than the forty-four-acre, 102-year-old lot in Culver City, California, that was long home to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and is now occupied by Sony Pictures.

The entrance features a giant rainbow that arches ninety-four feet in the air and evokes memories of The Wizard of Oz, which was shot here in the late 1930s. Walking down Main Street, into the heart of the lot, you stroll through a faux downtown lined with buildings named after Cary Grant, Frank Capra, Rita Hayworth, and David Lean, the stars and filmmakers who built the legacy of Columbia Pictures, which Sony acquired in 1989.

Walking farther, past posters for unforgettable Columbia movies like Lawrence of Arabia and Spider-Man, you come upon the studio store, with T-shirts, mugs, and DVDs of Sonys biggest hits from recent years, including 21 Jump Street, Breaking Bad, and the James Bond blockbuster Skyfall. Visit on the right day and you might see Will Smith drive by on a golf cart or Seth Rogen chowing down in the Harry Cohn commissary building, named after the larger-than-life mogul who cofounded Columbia with his brother and their friend in 1918.

All around you, meanwhile, are nearly thirty soundstages where everything from Gone with the Wind to Rocky to Wheel of Fortune has been shot.

Despite appearances, however, studio lots like Sonys are not what they used to be. Movies are rarely made on soundstages here, as production has fled to places like Georgia and London, in search of big government subsidies. The names of retired actors and directors may appear on the buildings, but the new generation of talent is far less powerful than the world-famous characters they bring to life, like Iron Man and Katniss Everdeen. The moguls who run the studios, meanwhile, have been brought dramatically down to earth and are increasingly indistinguishable from the MBAs who run retail chains and investment banks.