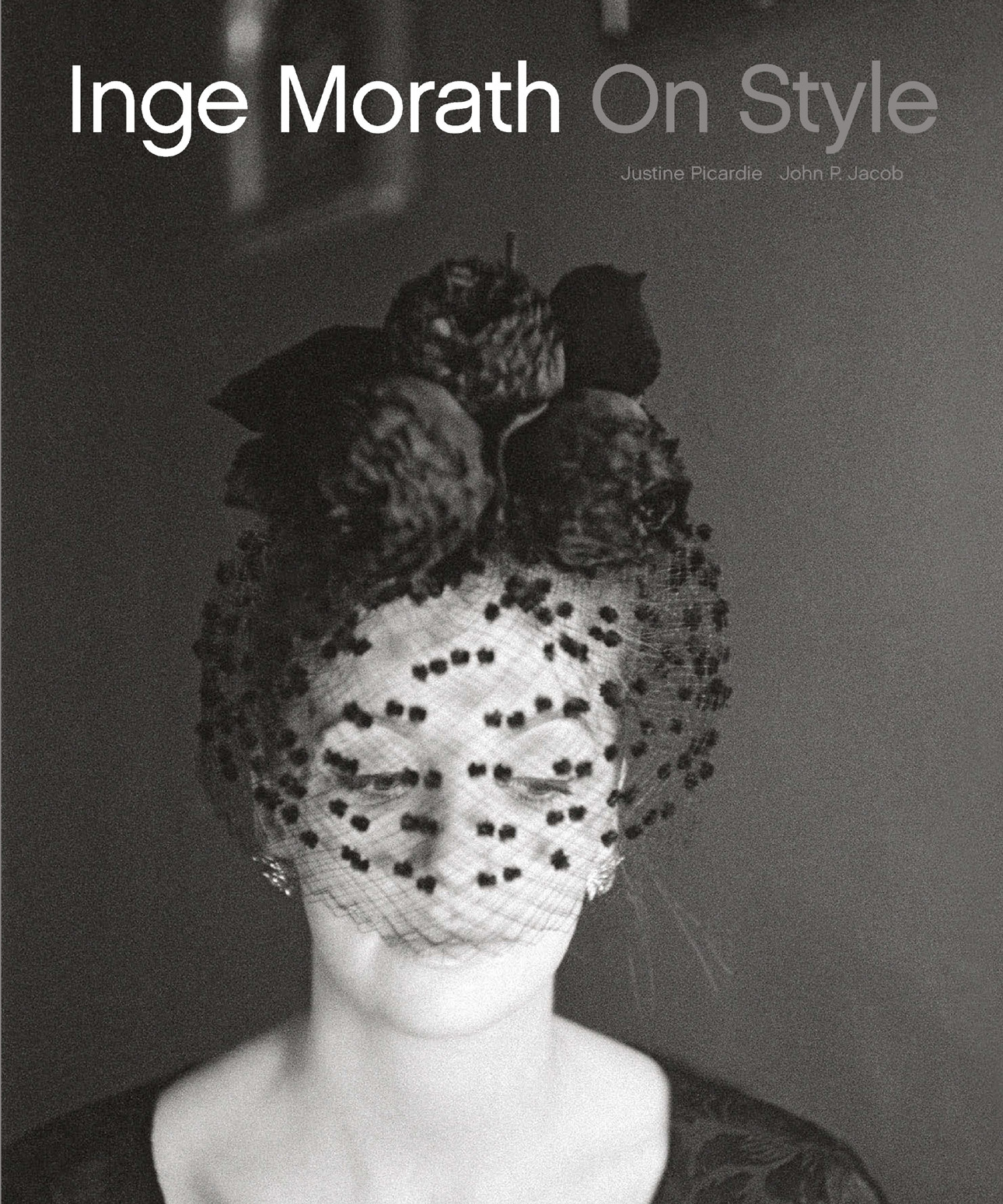

Introduction

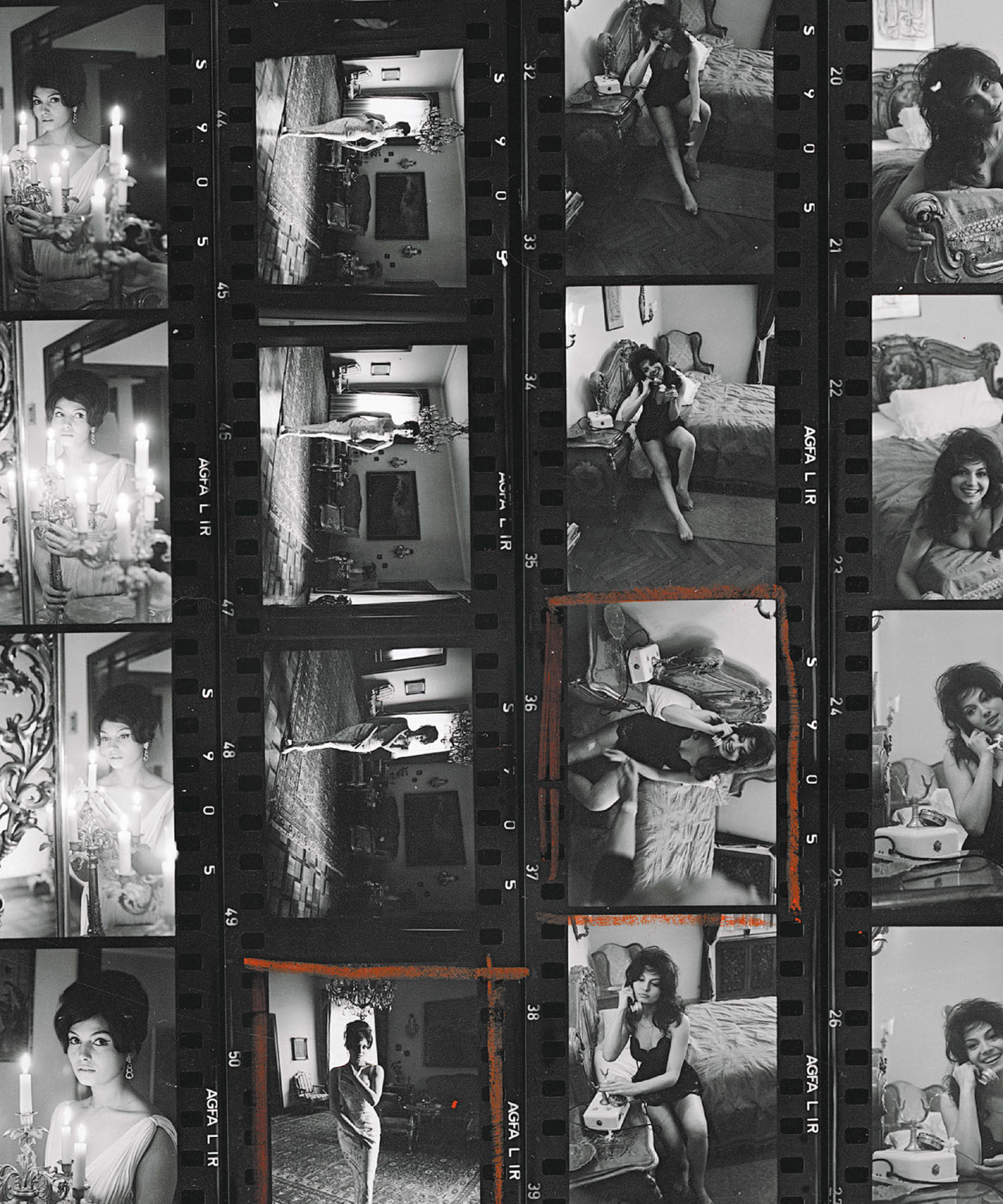

Justine Picardie

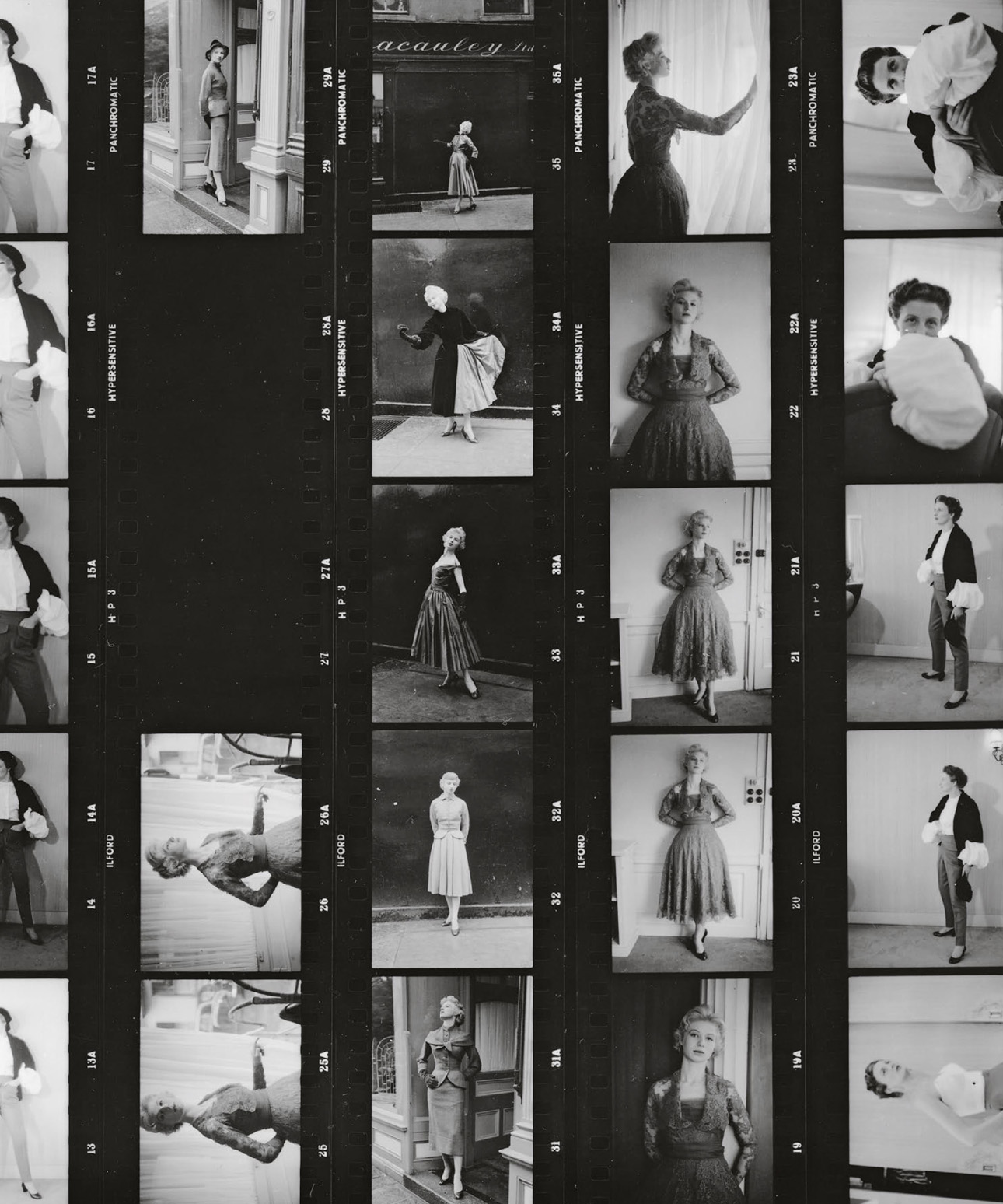

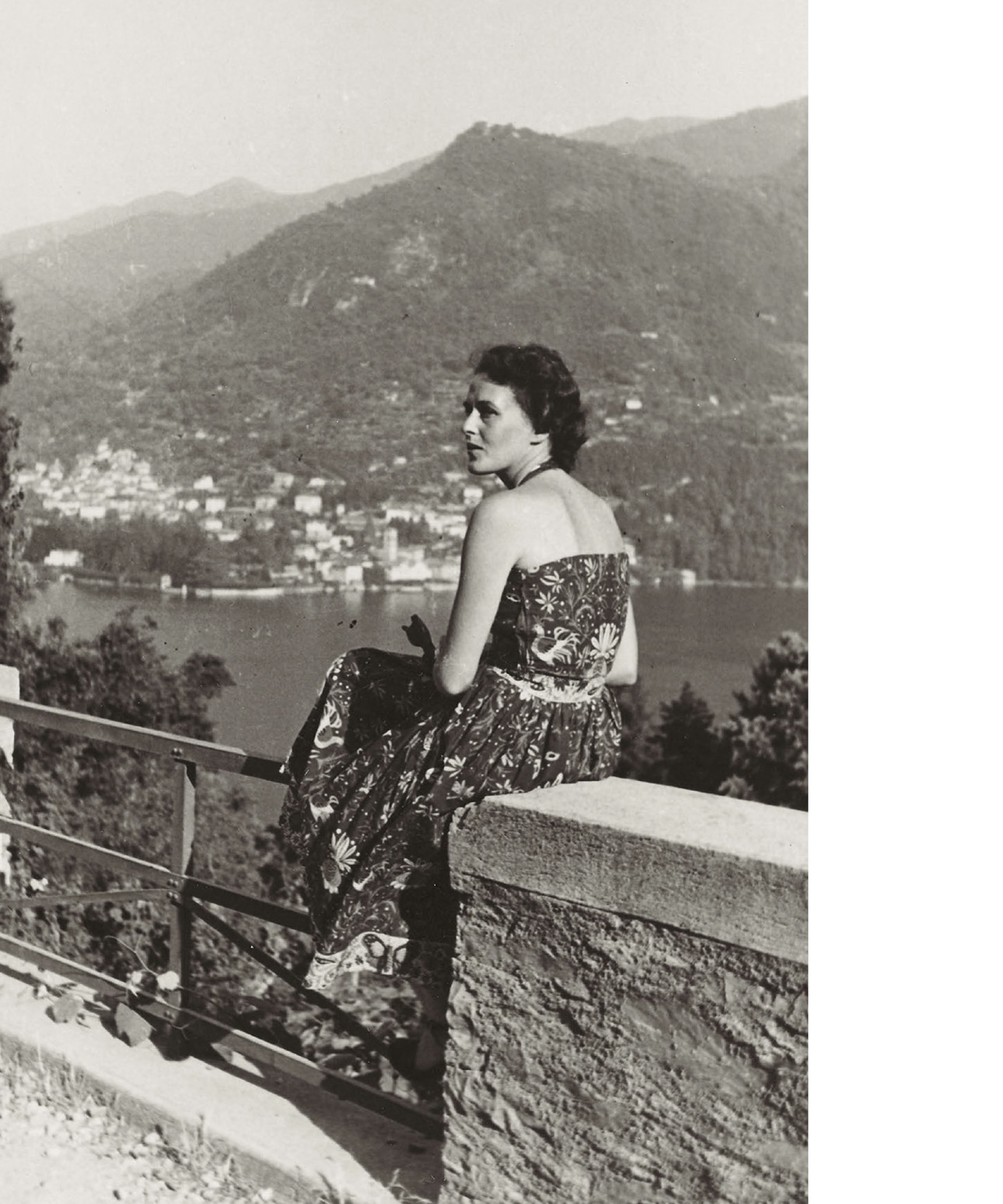

Inge Morath photographed during her first reportage trip with Magnum

Photos, Capri, 1949, photographer unknown

In 1998, Inge Morath was interviewed by the New

York Times on the occasion of a retrospective com-

memorating her seventy-fifth birthday. During the

interview Morath told a story about her life in Berlin

during the Second World War, when, having refused

to join the Hitler Youth, she was drafted to work in an

airplane factory alongside Ukrainian prisoners of war.

The forced labor brought her into constant danger,

as the factory was a frequent target for Allied attacks.

Between the bombings, said Morath, someone once

gave me a bouquet of lilacs and I held them up over my

head and ran through the bombed-out city.

Though this memorable image was created in words

rather than pictures, it might also be a clue to under-

standing the profound depth and subtlety of Moraths

photographs, even when she appears to be exploring

the beautiful surfaces of style. For all her wit and light-

ness of touch, there is often a sense of darkness beyond

the edge of the frame. How could it be otherwise, given

what she witnessed during the war?

Born in Austria in 1923, Ingeborg Morath was the

child of liberal Protestants, both research scientists. The

family was living in Germany at the outbreak of war,

and the horror and suffering that Morath witnessed

thereafter was to have a profound and enduring effect.

In the same interview with the New York Times (con-

ducted less than four years before her death), Morath

offered another telling image of her wartime experi-

ence: Everyone was dead or half dead. I walked by

dead horses, by women with dead babies in their arms.

I can't photograph war for this reason.

After the war, Morath's linguistic expertise led to

jobs as a translator and journalist in Munich and Vien-

na (she studied languages at university, and became

fluent in French, English, and Romanian as well as her

native German; to these, she later added Italian, Span-

ish, Russian, and Mandarin). By 1949, she was working

with the young Austrian photojournalist Ernst Haas,

and their talents were such that they attracted the

attention of Robert Capa, the legendary war photog-

rapher and co-founder of the Magnum agency (estab-

lished in 1947), who invited them to join him in Paris.

Interviewed by Alex Kershaw for his biography of Capa,

Morath recalled that she arrived in Paris on Bastille

Day 1949, and went straight to the Magnum office

on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honor. That night, Capa

took Morath out to dinner, and suggested that she

should acquire some stylish clothes; this she man-

aged soon afterwards, when she met the Spanish

couturier Cristbal Balenciaga at a party. I think he

liked me because I was doing this dicey stuff, and he

gave me a couple of suits, with pockets everywhere

for cameras and film. They were so elegantI still

have one! Anywayafter that, Balenciaga made all

my clothes for a long time.

There are several different ways that one might

interpret this story. It could be cited as evidence of

sexism (a macho war photographer telling a brave

young woman to dress in a more ladylike manner)

or of practical necessity (a smart suit would allow

Morath to make her way in the world). More likely

is that Capaborn Endre Friedmann in Budapest in

1913was possessed of an innate understanding of

style, since his parents had been successful dress-

makers. But what is also striking is the degree to

which Morath must have charmed the famously shy

Balenciaga, for he not only dressed her but subse-

quently allowed her to photograph him at home in

1959, at his country home, La Reinerie, near Paris.

By this point, a decade after her arrival in Paris,

she was a distinguished photographer in her own

right, and had been recognized as such by Mag-

num. (Having first joined the agency as a writer and

researcher, assisting its co-founder Henri Cartier-

Bresson, she became a full member in 1955).

Unlike her mentor Capawho died in 1954 after

stepping on a land mine while on assignment in

VietnamMorath continued to eschew war pho-

tography. But her courage and adventurous spirit

was never in doubt; her many foreign assignments

included a trip to Iran in the mid-fifties, where she

travelled alone for most of the time, dressed in a

traditional chador.

Morath was equally adept at discovering new

stories in more familiar places. In 1951, she moved

to London, where she started working for

Picture

Post and was briefly married to one of its journal-

ists, and subsequent editor, Lionel Birch. (She was

his sixth wife, and though the marriage lasted only

briefly, Birch, undaunted, went on to marry for a

seventh time.) Her atmospheric photographs of

London in the early fifties are a glimpse into a lost

world that was still clinging to the vestiges of tradi-

tion, such as the debutantes presentation at Court

and the customary rituals of the social season. Thus

one of Moraths most famous portraits, that of the