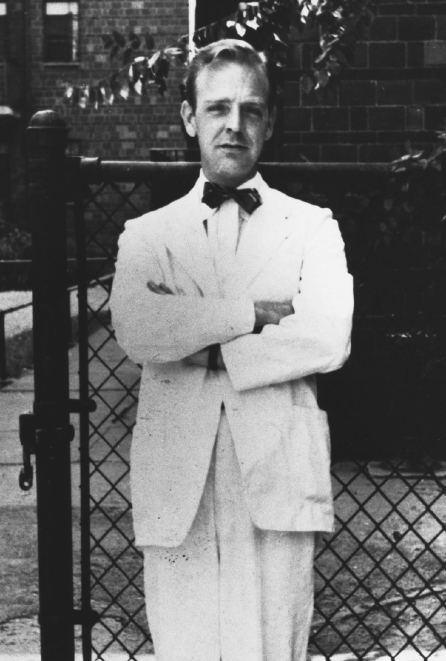

William Inge at George Peabody College in Nashville, 1935 (Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives).

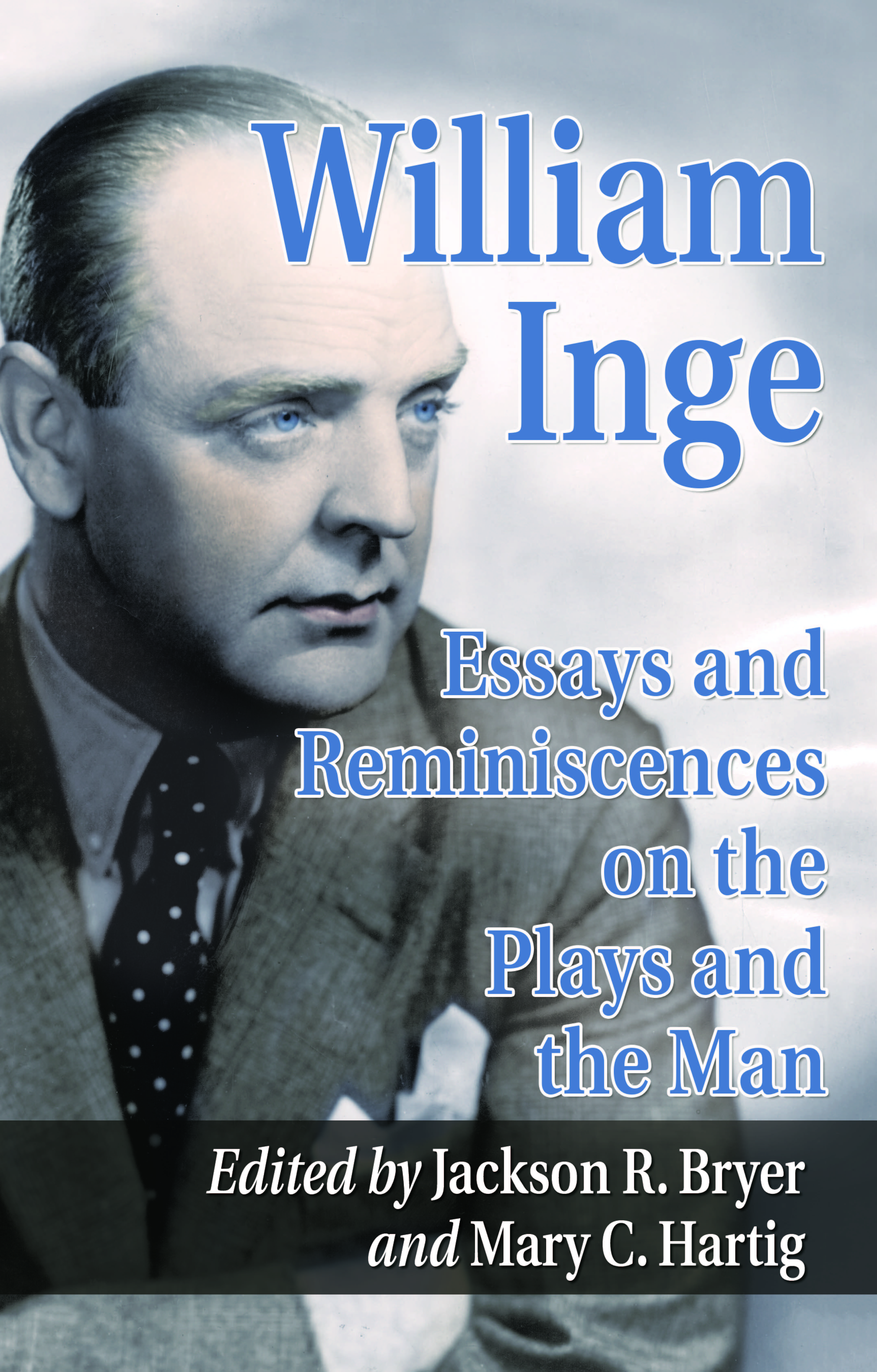

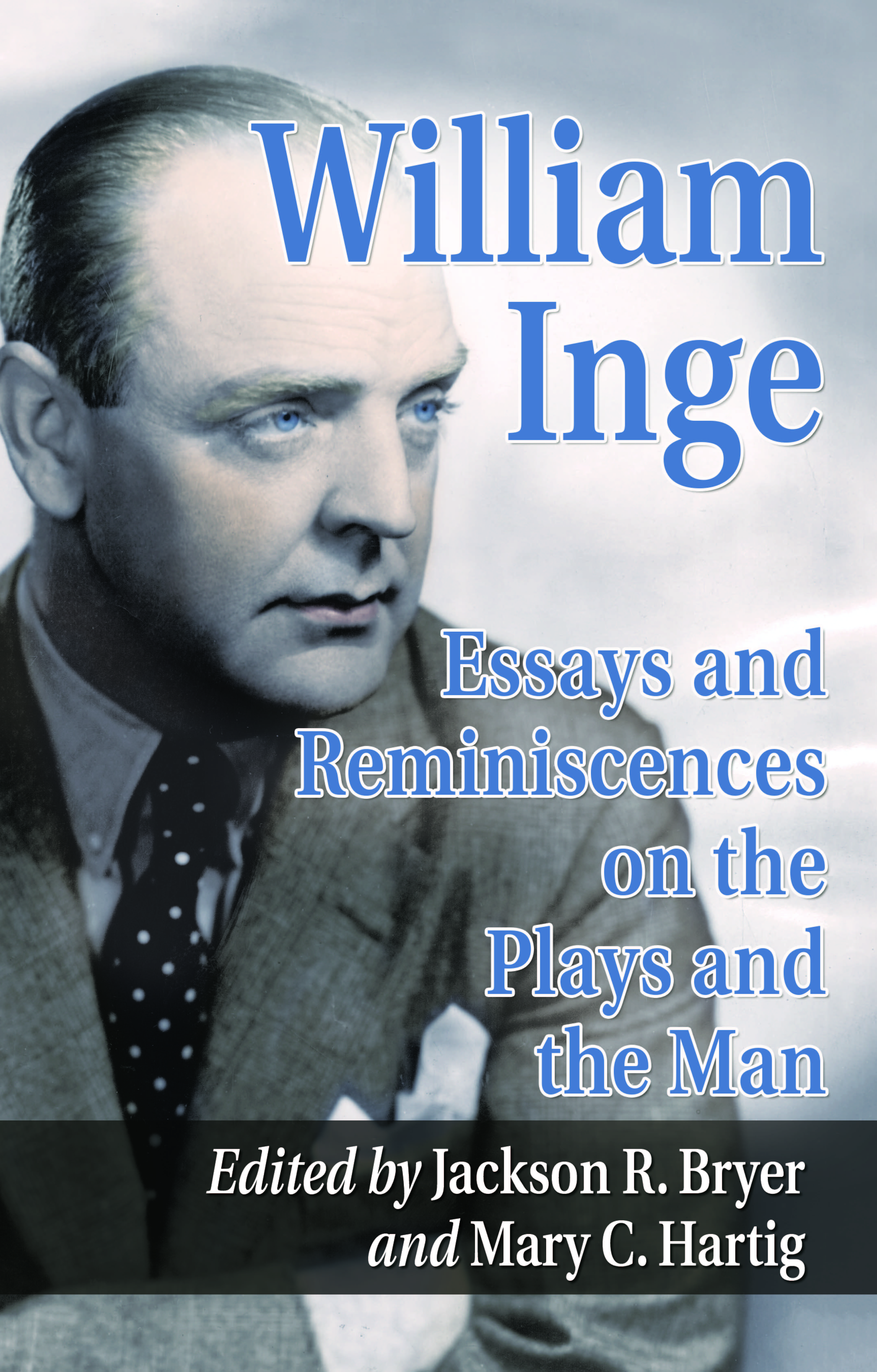

William Inge

Essays and Reminiscences on the Plays and the Man

Edited by JACKSON R. BRYER

and MARY C. HARTIG

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1632-2

2014 Jackson R. Bryer and Mary C. Hartig. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Playwright William Inge, circa early 1950s (Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Introduction

It is often forgotten, some sixty years later, that during the 1950s William Inge was not only the most commercially successful American playwright of the decade but also one of the most highly esteemed among critics. Between February 15, 1950, when Inge made his Broadway debut with Come Back, Little Sheba, and January 17, 1959, when his fourth successive hit play, The Dark at the Top of the Stairs, closed, no other dramatist matched his success. While Come Back, Little Sheba had a highly respectable but relatively modest run of 191 performances, Picnic, Bus Stop, and Dark at the Top of the Stairs each ran for more than 450 performances. When one adds to these statistics the fact that, in each case, a successful film version of the play, often with such major movie stars of the day as Burt Lancaster, Marilyn Monroe, and William Holden, appeared within a year or two following its stage debut, one can begin to understand Inges prominence. Typical of the high regard in which he was held by critics are Walter Kerrs remark, in his review of Dark at the Top of the Stairs, that Inge is one of the three or four ablest dramatists now working in the American theater (1) and Gilbert Millsteins observation in a 1958 Esquire article that [t]here is little question that Inge is today one of Americas three leading writers for the stage, his compeers being Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams (60).

Inges success can be attributed to a number of factors. The seemingly simple humanity of his characters and the honesty and empathy with which he depicted them in easily identifiable, mostly domestic, situations certainly struck a responsive chord with a 1950s postWorld War II audience that was living through the Eisenhower years and emerging chastened from the horrors and traumas of the 1930s and 1940s. On one level, Inges plays seemed to be just the sort of homespun, easily understood depictions of American life that appealed to a generation weary of political conflict and social upheaval. Sophisticated and urban New York audiences also undoubtedly found something vaguely exotic and refreshing in the small-town Midwest settings and predicaments depicted in Inges plays. Whatever the reasons, the plays were extremely popular on stage and on screen during the decade of the 1950s; that the mood of the time had something to do with Inges success is testified to further by the fact that, as the 1950s ended and the 1960s, a very different decade, began, Inges fortunes declined precipitously. His last play of the 1950s, A Loss of Roses, which opened on November 28, 1959 (a mere ten months after Dark at the Top of the Stairs ended its highly successful run), lasted less than a month (for many years thereafter, Inge referred to it as his favorite among his plays).

As the 1960s began, Inge felt the changes that were occurring and believed that he had to adjust to them. As he explained to Digby Diehl in 1967, I think any creative person who is going to survive more than a decade or so has to find himself anew periodically because he has to change with the times. I know that the kind of play that was being done in the fifties has no audience now. And I know that I dont have the same kind of approach to writing as I did in the fifties. I seem to be dealing with more metaphysical material (Inge, William Inge 51). Whatever his motives, Inges attempts to change with the times and deal with more metaphysical material failed. Although his screenplay for Splendor in the Grass (1961), which won him an Academy Award, was set in the rural Midwestern milieu that had brought him so much recognition, his two Broadway plays of the 1960s, Natural Affection (1963) and Wheres Daddy? (1966), each abandoned that setting in favor of urban locations, Chicago and New York, respectively; the former attempted to be relevant by emphasizing the violence of the day and the latter did the same by including a black couple and an openly gay character. Both closed shortly after they opened; and the one-act plays he wrote during this period, many of whichpresumably in a similar effort to reflect the less repressive atmosphere of the timedealt directly with such subjects as homosexuality and depression, topics central personally to Inge that he had not felt able to confront in the 1950s, were not produced. While these later plays are arguably simply not as good as his four hitsprobably because Inge veered away from the settings, characters, and situations about which he felt most deeply in favor of what he thought the times demandedit is also true that the audiences of the 1960s wanted a theater very different from what Inge offered, no matter the shift in his subject matter. Where realism was the stock in trade in the 1950s, the 1960s saw the rise of the Theater of the Absurd and of a far more experimental theater than that presented in any Inge play.

Although he had suffered for many years from depression, alcoholism, and the anguish of being a deeply closeted homosexual, these difficulties intensified in the 1960s and early 1970s, culminating on June 10, 1973, when he committed suicide. At the time of his death, while his four successful plays were being done quite frequently by amateur groups, the professional theater had pretty much forgotten about him. In 1982, Margaret Goheen, a speech and theater teacher at the community college in Inges hometown of Independence, Kansashe had attended the college briefly in 193132 during a depression-enforced return homewanting to publicize the colleges acquisition of Inges papers (some left in his will and others donated by his sister Helene), organized a one-day Inge Festival on May 3rd in celebration of the playwrights 69th birthday. In 1983, the Festival was expanded to three days and featured the selection of Inges close friend, fellow playwright Jerome Lawrence, as the recipient of the first William Inge Award for Lifetime Achievement. Three decades later, the annual William Inge Festival, now a four-day event, is thriving; and the recipients of the Inge Award have included virtually every major American playwright of the past six decades, all of whom were present to receive the honor. The Festival has attracted increased media attention in recent years; and there is little doubt that it contributed to a gradual resurgence of interest in Inge and his plays. There have been major New York revivals of

Next page