Table of Contents

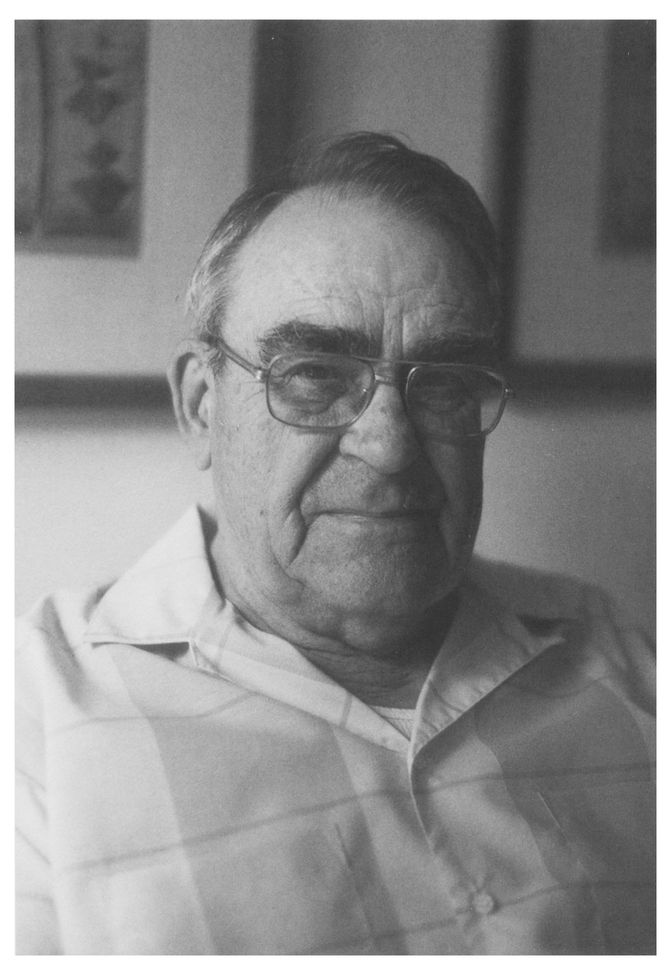

Arnold Williams (1907-1992)

In Memory of Arnold Williams

Abbreviations

| BL | British Library |

| ChR | Chaucer Review |

| CUL | Cambridge University Library |

| e.s. | extra series |

| EEDS | Early English Drama Society |

| EETS | Early English Text Society |

| EHR | English Historical Review |

| ELH | English Literary History |

| ELR | English Literary Renaissance |

| fol(s). | folio (s) |

| MED | Middle English Dictionary |

| MS(S) | manuscript(s) |

| MSR | Malone Society Reprint |

| N&Q | Notes and Queries |

| n.s. | new series |

| OED | Oxford English Dictionary |

| PL | J.-P. Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Latina. 221 vols. |

| PMLA | Publications of the Modern Language Association of America |

| REED | Records of Early English Drama (Toronto) |

| RES | Review of English Studies |

| S.D. | stage direction |

| s.s. | supplementary series |

| sc. | scene |

| ShQ | Shakespeare Quarterly |

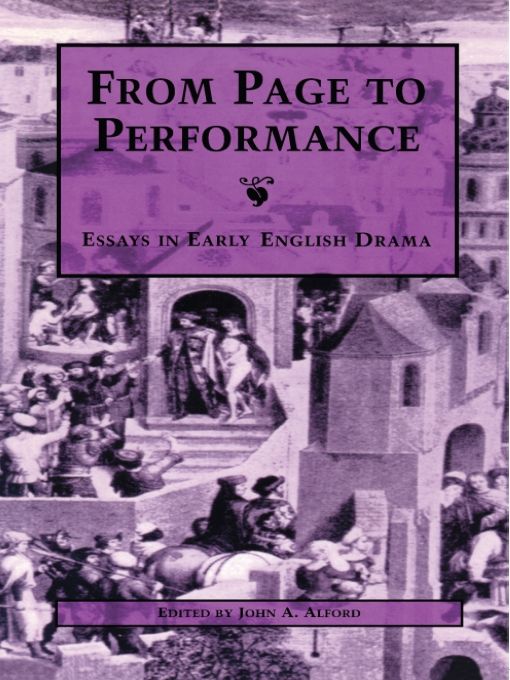

Introduction

It is a truism that reading a dramatic script is like reading a musical score. Whatever impression may be conveyed by the printed page, the only measure of worth that matters ultimately is performance.

The point hardly needs stating in the case of modern drama. The Importance of Being Ernest or A Streetcar Named Desire are stock repertory because of their proven appeal as theater, and more people are likely to have seen these plays than to have read them. The reverse is true of our knowledge of earlier drama. Generally speaking, our only experience of a liturgical play like the Beauvais Daniel, or a Tudor morality like Fulgens and Lucrece, or even some of Shakespeares plays, has come through books.

The letteraturizzazione of early dramato borrow George Kennedys term for the process undergone by another oral art, rhetoric, as it moved from the forum to the schoolroom Critics nowadays are less likely to speak in such terms. The fact that our knowledge of these older plays still comes primarily from reading continues to affect our critical judgments, of course, but the subtler challenges are now in the area of critical interpretation. The improper application of literary methods to dramatic works has resulted in interpretations that would be difficult or impossible to sustain in any actual performance.

The late Arnold Williams was especially sensitive to the confusion of literary and dramatic methodologies. One instance that came under his scrutiny was typological criticism. Williams readily conceded that the cycle playwrights choices of particular biblical stories might have been determined by typologya standard tool of medieval biblical exegetes, who assumed, for example, that Abrahams sacrifice of Isaac was intended to be a type or prefiguration of the sacrifice of Christbut he questioned how far this interpretative method could be pushed within individual plays.

[M]edieval drama ... was produced in conditions almost strictly analogous to those governing a modern film or television program. There was no way by which anyone could experience the Second Shepherds Play except by witnessing it.... The kind of typology such an audience could effectively absorb had to be simplified, common, obvious. It will not do to cite Irenaeus, Tertullian, Augustine, Aquinas. These are as remote to the medieval audience as are Robert Graves or Maud Bodkin to the television viewer of today, and remoter than Marx or Freud.... I am persuaded that most typologists forget this. They are suggesting meanings appropriate for literary texts but inappropriate for the stage.

Williams was not opposed to typological interpretation as such. If any suggested typology is capable of representation on the stage, and if it enhances and deepens the meaning of the piece, let us accept it (1968, 681). From his own experience, however, he was convinced that more often than not the use of typology produces bad theater (683). In drama the ultimate test of meaning, as of artistic value, is performance.

For Williams, therefore, the modern production of medieval drama was, among other things, a research tool, a form of inquiry no less important than the study of its cultural context and history; and much of his career was given to promoting the performance of these old plays. His classes in medieval drama at Michigan State University, where he taught from 1939 until 1974, often involved the blocking and acting out of scenes, and sometimes culminated in full-scale productions open to the public. A few of these (Mankind and the Wakefield Second Shepherds Play), directed by his student William Marx, were presented before even wider audiences at annual meetings of the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo). It was also Williamss thoughts on the value of performance, delivered at a meeting of the Modern Language Association in 1965, that inspired John Leyerle to organize his first graduate seminar at the University of Toronto around the production of a medieval playthe beginning, as it turned out, of the Poculi Ludique Societas, for many years the most active medieval and Renaissance play group in North America. When the British Broadcasting Corporation decided to make its performances of The First Stage (English Drama from its Beginnings to the 1580s) available on phonograph record, it was to Williams that the publisher turned for the program notes. In short, it can be said that Williams, as much as anyone else in modern times, helped to bring early English drama back to life.

The subject of this book, written expressly to recognize Arnold Williamss contribution to our understanding of early English drama, is, most appropriately, dramatic performance. All twelve essays-whether focused mainly on dramatic texts or on actual productions, both early and modernare bound by a keen awareness of the difference between the two, of the pitfalls that lie in the way (as Williams so often reminded us) from page to performance.

In the first essay T. P. Dolan argues for a correlation between lay literacy and clerical approaches to the Mass as a performance text. As congregations were gradually shut out from an understanding of the Liturgy by their ignorance of Latin, many priests compensated by trying to make the Mass more dramatic. In this they were guided primarily by the typological interpretation of Amalarius of Metz (d. 850), who connected each stage of the Mass with an event from the last days of Christ. Like Williams, Dolan is concerned with how and to what extent such typologies could be communicated by performance. Drawing upon the text of the York Rite, as found in the vernacular Lay Folks Mass-Book, he attempts to come to some conclusions as to the degree of passivity or activity experienced by members of the congregation at Mass.

Next page