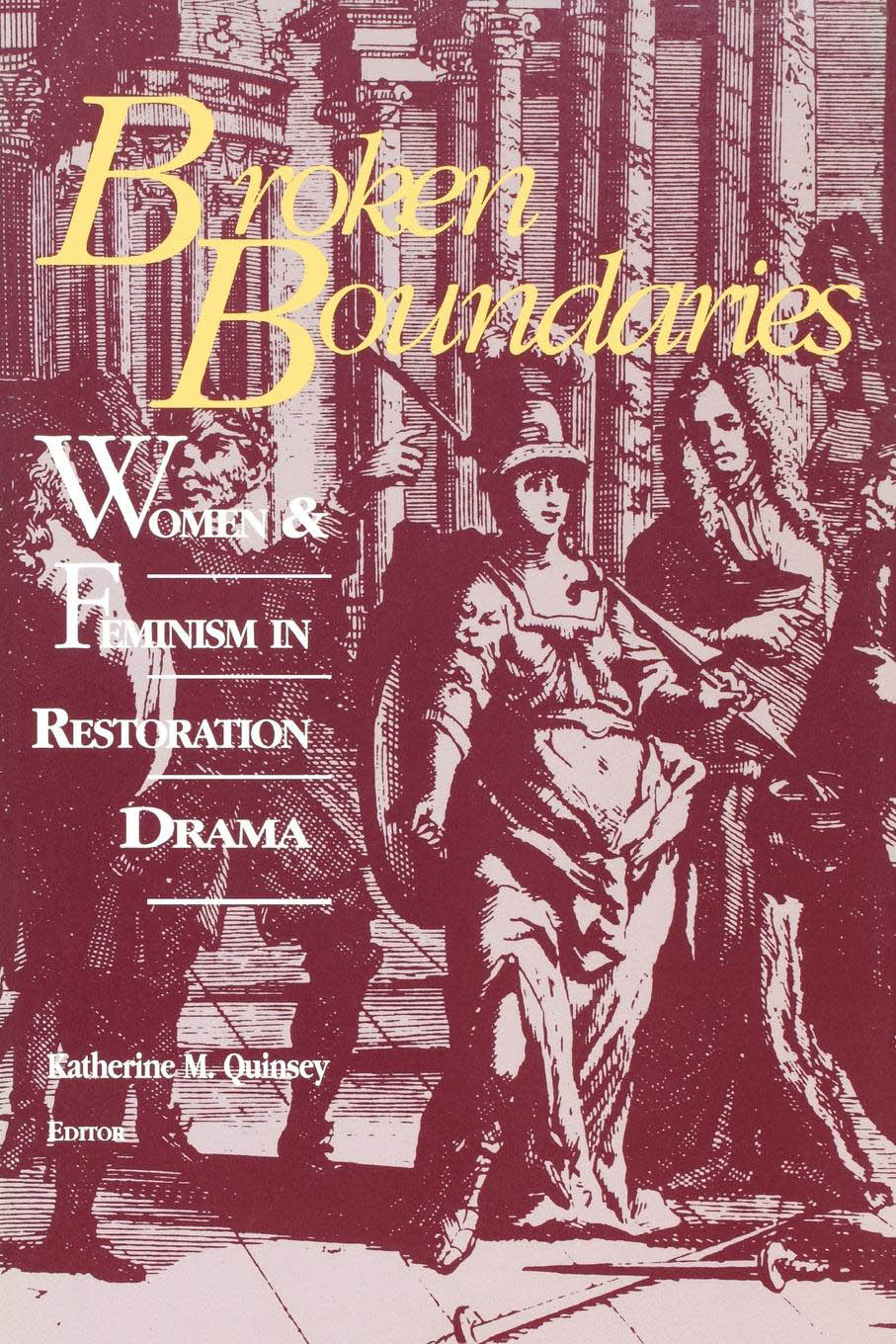

Broken

Boundaries

Broken

Boundaries

Women & Feminism in Restoration Drama

Katherine M. Quinsey

Editor

Frontispiece: Nell Gwyn rising from the dead to speak the epilogue to Drydens Tyrannick Love, published as the frontispiece to A Key to the Rehearsal (1714) in The Dramatick Works of his Grace George Villiers, late Duke of Buckingham (1715), vol. 2. By permission of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Copyright 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 405084008

00 99 98 97 96 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Broken boundaries : women and feminism in Restoration drama / edited by Katherine M. Quinsey.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0813119456 (alk. paper). ISBN 0813108713 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. English dramaRestoration, 16601700History and criticism. 2. Feminism and literatureEnglandHistory17th century. 3. Literature and societyEnglandHistory17th century. 4. Women in the theaterEnglandHistory17th century. 5. Women and literatureEnglandHistory17th century. 6. TheaterEnglandHistory17th century. 7. Gender identity in literature. 8. Sex role in literature. 9. Women in literature. I. Quinsey, Katherine M., 1955

PR698.F45B76 1996

822'.409352042dc20 96-5329

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to my research assistant, Maria Magro, for her exhaustive, precise, and intelligent proofreading of this volume in manuscript, and to Mrs. Lucia Brown and her team at the University of Windsor for their admirable efficiency in preparing it for press. Above all, as editor I should like to express my deep appreciation for the grace, efficiency, and professionalism shown by each of the contributors to this collection, in every stage of our working together: they have embodied scholarship in all its best senses.

Introduction

Katherine M. Quinsey

Restoration drama is overwhelmingly concerned with questions of gender identity, sexuality, and womens oppression, to a degree and a depth not seen in a comparably popular form of entertainment before or since. It stands out among the mainstream literary and artistic forms of its time in its unusually direct, probing, and fluid way of engaging certain radical questions: questions about the place of women in social and familial structures, about male/female relations, about the nature of womenand menthemselves. It is a remarkable index to the centrality of the woman question in this period that this most popular verbal form of entertainment, a peculiarly self-conscious form that blurs, even erases, the boundaries between its fiction and the social world of the audience, should be dominated by gender issues. Restoration drama is deeply embedded in its social matrix, yet in both its authorship and its production, as well as in its challenge to fictionality and its unresolved dialogic interplay, it continually separates itself from that matrix, reflecting and generating social change.

The late seventeenth century is a pivotal period in womens social history and feminist awareness, to some extent culminating a process of ontological questioning of gender begun much earlier, and thus differing significantly from later eighteenth-century vindications of womens rights. It is now a commonplace that the seventeenth century spans the shift from an earlier concept of gender as a variation in an essentially unified human nature to a hardening of gender categories, which theorized female as distinct in essence from male in all levels of existencebiological, spiritual, intellectual, and social. It has also been generally observed that the cataclysmic changes in the intellectual, political, socioeconomic, and religious frameworks of seventeenth-century England were not extended to matters of gender; as old frameworks of authority were fundamentally altered, those supporting patriarchal social and economic structures were merely reconfigured. Indeed, within seemingly more egalitarian socioeconomic and political models, the equation of women and propertywomens status as chattels and as passive channels of property exchangewas entrenched, and female power and autonomy were markedly lessened. The Restoration period, however, which saw traditional order outwardly restored but conceptual and discursive frameworks radically and permanently altered, is characterized by its discursive instability: a volatile mixture of question and (sometimes violent) reassertion, action and reaction, searching skepticism and conservative affirmation. This period bridges the differing essentialisms of the Renaissance and the eighteenth century with a fluid and dynamic questioning of the assumptions underlying both. Such questioningwhich in its cutting through to the roots can only be called feministboth springs from and itself promotes the unsettling of frameworks of perception in all areas of intellectual and social life. Consideration of the feminist questions in Restoration drama, then, should promote a reexamination of all the intellectual, political, and socioeconomic shifting taking place in the period.

Restoration drama is perhaps the most telling popular expression of these radical uncertainties. It probes, shifts, and juxtaposes frameworks of value, exposing the arbitrary nature of certain social structures even in the act of affirming them. Encouraged by the physical presence of women onstage as actresses, the increased and varied representation of women in the audience, and the entry of women into the public sphere as writers, and driven by the larger and deeper ideological shifts underlying these phenomena, this drama enacts a deeply ambivalent engagement with questions of female subjectivity, greatly expanding speaking roles for women and playing almost obsessively on the presence of women in the theater. The depth and extent of its interest in sexual roles, relationships, and identities can be seen in its adaptations of Renaissance models, such as John Dryden and William Davenants