Copyright 2009 by Henry Alford

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Excerpt on page 200 from Little Gidding in FOUR QUARTETS, copyright 1942 by T.S. Eliot and renewed 1970 by Esme Valerie Eliot, reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Excerpt on page 200 from Burnt Norton in FOUR QUARTETS by T.S. Eliot, copyright 1936 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Company and renewed 1964 by T.S.Eliot, reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Excerpt on page 213 from East Coker in FOUR QUARTETS, copyright 1940 by T.S. Eliot and renewed 1968 by Esme Valerie Eliot, reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group,

237 Park Avenue,

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing.

The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: January 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-54440-5

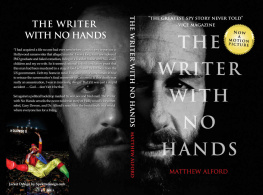

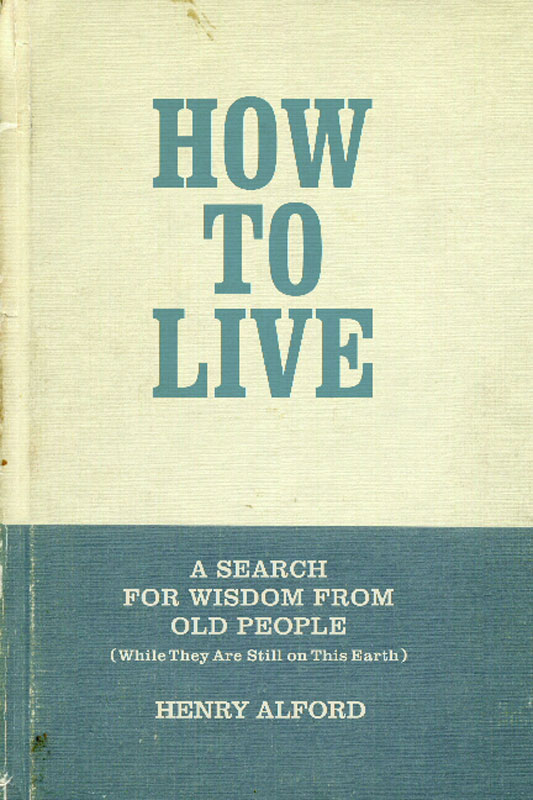

also by Henry Alford

Big Kiss: One Actors Desperate Attempt to Claw His Way to the Top

Municipal Bondage: One Mans Anxiety-Producing Adventures in the Big City

I t is commonly saidbut I believe it anywaythat old people are wise. I dont mean that anyone who hits the age of seventy or so suddenly starts speaking in haiku or engaging in the kind of hyperextended, meaning-drenched eye contact that makes you look nervously down at the floor in search of a dog to pet.

No. Rather, I think that the older we get, the more life experiences we are likely to haveand the more experiences we have, the greater the body of information we have to work from. I happen to think that there are some very wise thirty-year-olds out there in the world, toobut the chances of an eighty-year-olds knowing something important about life are much greater.

We humans are one of the few species with an average life span that extends beyond the age at which we can procreate.

Why is this?

Maybe its because old folks have something else to offer.

EVERY YEAR OR SO, I have an epiphany about some aspect of life. Usually, these insights are small. Take, for instance, the one I had a few years back, after buying a lot of food for a breakfast I was making for some friends. Having carefully selected an assortment of bagels, which I then gingerly placed into a brown paper bag, I was struck, two hours later, by a very, very, very profound realization: a bag of assorted bagels with one garlic bagel in it is a bag of garlic bagels.

But sometimes my insights are larger. Sometimes they reveal to me truisms about life or people and compel me to sit up and take notice. (And truisms about life or people is, in this instance, what Im talking about when I say wisdom. Im not talking about quantum theory or knowledge comprehensible only by experts.) When this knowledge is of a universal nature, it almost unavoidably verges on being clichdtake my realization, after a long and difficult friendship with a strikingly candid friend whose bald assertions often hurt my and others feelings, that our greatest strengths (her candor) are usually our greatest liabilities (her candor).

When this knowledge is of a more personal nature, it can hit you with all the subtlety of a gonglike my discovery, once Id determined that neither my crush-inducing cinema-studies professor nor my charismatic boss at my first job nor the attractive young intern I trained at that job reciprocated my affections, that most crushes are narcissistic. Their engine is flattery.

BUT THERES ANOTHER KIND OF WISDOM, toothe ability to predict the consequences of certain actions. This kind of knowledge is even more hard-won, forged as it is in the crucible of failure. And, unlike truisms about life and people, which are sometimes articulated by the young, the ability to predict consequences is almost necessarily a function of advanced years: to know that A, when followed by B, leads to C, is to have seen A and B in some rather compromised situations, very possibly at 2:00 a.m. in their underpants, in front of the kitchen sink.

This ability to predict consequences does not operate without effort. Sherwin Nuland, the clinical professor of surgery at Yale who wrote How We Die, writes in The Art of Aging, Man is the only animal to have been granted the ability to continue developing during the later periods of life, and much of this depends on seeing oneself as the kind of person who can overcome the tendency to do otherwise.

As songwriter Eubie Blake, who lived to ninety-six, said, If Id known I was going to live this long, I would have taken better care of myself.

FOLLOWING MY LINE OF LOGIC about aging and insights, you might think that I believe that a typical ninety-year-old is twice as wise as a typical forty-five-year-old. I dont. I dont because we humans tend to forget things. We must account for attritionvaluable information is slipping through the cracks in the wall and seeping into the bed linens and evaporating into the current Boca Raton weather system.

But maybe I can catch and curate some of it before it slips off into the night.

WISDOM IS SLIPPERY. It comes in many forms and guises. Sometimes it is intermingled with a certain amount of unwisdom.

But however difficult wisdom can be to pin down, one thing is certain: the curtains dont come crashing down when you hit seventy. In fact, the years after threescore and tenthe decade that Psalms 90 tells us is the span of our lives because anything after eighty is only labor and sorroware a ripe time for realizations and breakthroughs. The reasons for this are varied. For some people, retirement finally gives them the time to contemplate their navels. Some come to conclusions as a result of their or others increasing proximity to the end. Cicero wrote in 44 B.C., Since [nature] has fitly planned the other acts of lifes drama, it is not likely that she has neglected the final act as if she were a careless playwright.

We tend to think of life after seventyoutside of medical ailments, of courseas being soft and muzzy and fairly static: lots of cardigan sweaters and an increasingly housebound devotion to a small, irritable pet. But for many people, its anything but. Grandma Moses started painting in her seventies; Michelangelo finished sculpting the Rondanini Piet when he was nearly ninety. Benjamin Franklin helped frame the U.S. Constitution at eighty-one; Golda Meir assumed leadership of Israel at seventy, and Nelson Mandela assumed leadership of South Africa at seventy-six.

Others arent starting new projects or professions or life situations but are altering their involvement with professions or life situations theyve been in for yearsrethinking their marriage, changing how they write or paint, deciding never ever again to tolerate anyone who calls them Dollface. In 2006, Newsweek ran a story about how eighty-seven-year-old preacher Billy Graham, whod spent most of his adult working life in the spotlight, had in his old age shifted his animus from partisan politics to the purely heavenly. The former political gadabout now refused to offer either an opinion on stem-cell research or counsel to world leaders. He told the magazine, The older I get, the more important the eternal becomes to me personally.

Whatever the realizations are that these older folks makeand whether these realizations apply only to themselves or have a more universal natureits safe to say that these mental breakthroughs are not always easily won and that the paths that lead to them are sometimes full of misdirection. As with any creative process, there is often a period of doubt and mental thrashing.