Inges confirmation.

Alberts business card.

Albert and Frieda at home.

Share of votes for the National Socialist German Workers Party, March 1933. (By Wikimedia Commons user Korny78. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5 (

Albert by the River Pregel.

Kurt Lange. (Courtesy of Das Bundesarchiv. BArch, Image R 2501/15093):

Gisela as a girl.

Dorothea with Carl, Wolfgang and Gisela.

Dorothea as a young mother with Carl.

Inge and friends by the sea.

Inge and Beatrice.

Beatrice, aged one.

Map of the Red Army advance, 1945. (Courtesy of Brinn Black):

Inges ration card.

Inges passport photo.

Vestre Kirkegrd.

Inge and Beatrice.

Gisela as an adult.

Wolfgang as a soldier.

Dorothea toward the end of her life.

Dorotheas suicide note.

Wolfgang in later life.

U.S. military document from Berlin Document Center.

Lindenborg Castle.

Wolfgangs grave.

The Monster, Kaliningrad. ( Mats Boesen):

Knigsberg manhole cover. ( Mats Boesen):

German grave used as paving stone.

PROLOGUE

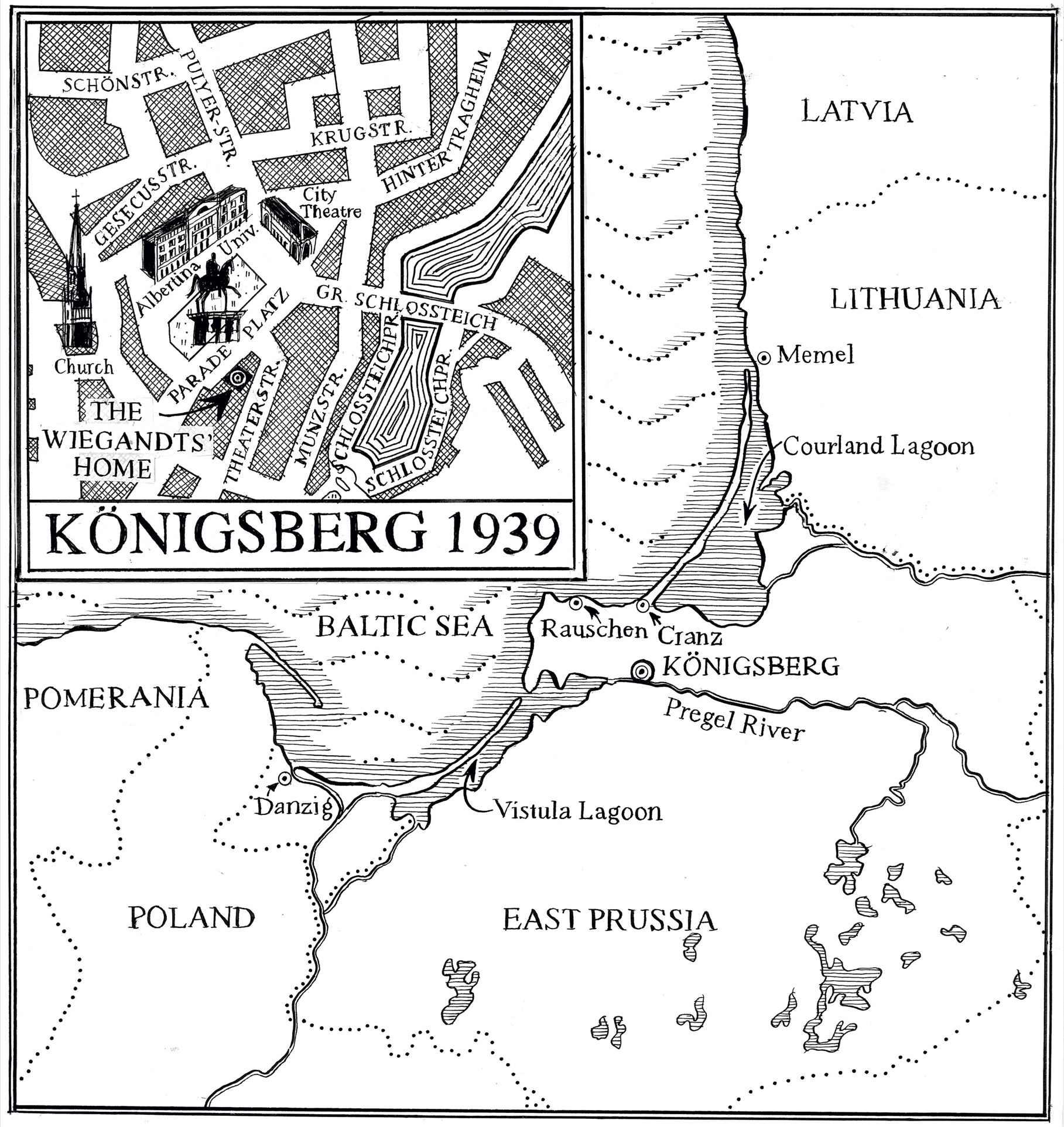

Knigsberg, June 1932

Albert Wiegandt folded his newspaper in half, obscuring the front-page headline: SEVEN INJURED IN KNIGSBE RG STREET FIGHTS . Stacking it into a neat pile with his papers, he locked everything in his desk. Every Friday without fail, he left the office early, at 3.30 p.m., to take his daughter, Inge, for a hot chocolate at the Cafe Berlin. The small, blue-fronted establishment near Knigsbergs Paradeplatz, busy with tourists in summer and students from the nearby Albertina University the rest of the year, was rather unprepossessing at first glance. It had simple wooden chairs and tables, and none of the plush leather upholstery of the old towns most fashionable restaurants. The cafes success lay in its reputation for serving the best hot chocolate in the old town. It was so thick your spoon would almost stand up on its own when you tried to stir it, and was served in large white porcelain cups that smelled of cinnamon and cocoa, topped with rich whipped cream, with a pot of milk to thin it on the side.

Those Friday afternoons were a favorite ritual of theirs. Albert had first taken Inge to the cafe when she was five, as a special treat, to allow his wife Frieda an hours undisturbed practice at the piano; a grateful Frieda, whose playing had suffered a little from the demands of motherhood, had encouraged the habit ever since. He and Inge would sit together and he would tell her about the latest happenings in the wine and spirits trade, which restaurant had placed the biggest order, and who was making the best schnapps. Inge would tell him about her week at school, which lessons shed enjoyed the most, which girls were in trouble with the teacher, and which tricks they had played on each other; he would laugh heartily over every scrape and commiserate over the small trials of a schoolgirls life.

Inge was born in July 1924, two years after her parents marriage, and had come to them almost as a miracle, as Albert and Frieda had met and fallen in love late in life. Albert was forty-five and Frieda thirty-nine at the time of Inges birth. She was now eight years old, a pretty, blue-eyed girl with thick, dark curls, a quick smile, and a vivacious manner. She was an only child and, though charming, could be demanding too. Her parents, and sometimes even the other inhabitants of their block of apartments, indulged her more than they ought.

Albert took off his jacket as he made his way to the Altstadt where they lived, in Knigsbergs very center, to collect his daughter. It was a warm afternoon, presaging the intense heat that often descended on the city at the height of summer. A farmers son from Grnwalde, some 150 kilometers east of Knigsberg, as a young man Albert had turned his back on a life spent working the land, with its harsh winters and isolation, to make his name as a merchant. He loved the city with the zeal of a convert; it held the refinement, the bustle, and the success he had been denied in childhood, which he relished. With his attractive, cultured, musical wife and his little daughter, he had achieved everything hed ever wanted, but he had been somewhat troubled of late.

As he walked, he thought again about the article that he had read that morning in Knigsbergs liberal newspaper, the Knigsberger Allgemeine Zeitung, about the clashes between local communists and the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary group led by the NSDAP, the new Nazi Party, which was growing in popularity all over Germany. It had reported terrible beatings: a young man of twenty-three lay close to death. It was the latest in a series of incidents that had plagued Knigsberg in recent months.

Albert had previously dismissed clashes between Nazis and communists as something that happened in the distant capital, Berlin. But their increasing frequency in Knigsberg was starting to bring the violence and agitation of Germanys new political era uncomfortably close to home. Politically, Albert was a centrist, a soft conservative with liberal leanings, who disliked violence and only bothered about politics if they affected his business as an importer of fine wines and spirits, or his more recent venture, a schnapps factory. He had joined the trade after returning wounded from service as a soldier in the First World War, before a legacy from his father helped him set up on his own. Business had been tough to start with; the aftermath of the war had brought great poverty, and it was some time before luxury goods such as wine and fine spirits flourished as they had before the war. Germans who had endured wartime starvation found they fared little better in peacetime, as punitive reparations crippled Germanys economy, bringing persistent food shortages and hyper-inflation.

In spite of all these difficulties, Albert had persisted, and his hard work had paid off. His business provided him with a comfortable income, and he dearly loved his family. But things were changing; his social circle included a number of Jewish friends, and he was not blind to the Nazi Partys violent anti-Semitism, the attacks of its Brownshirt gangs, or its alarmingly populist rhetoric. His wifes uncle, a professor of botany at Albertina University, whose judgment he respected, had convinced him early on that the Nazis were criminals and thugs. Anti-Semitism had been on the rise throughout the 1920s, fueled by the harsh economic climate, but the waves of attacks on the Jewish community always eventually subsided. Albert did not know that only a few weeks later Nazi gangs would turn Knigsbergs streets into a bloodbath, in a series of murders and attacks they styled as a revolt against communist terror. The federal elections of July 31, 1932, would unleash a wave of terror in which Nazi activists killed twenty-five people, including the editor-in-chief of the socialist newspaper