PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2014

Published in Penguin Books 2015

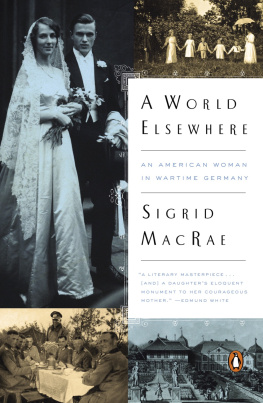

Copyright 2014 by Sigrid MacRae

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Excerpt from This Cruel Age Has Deflected Me... by Anna Akhmatova from Poems of Akhmatova, selected, translated and introduced by Stanley Kunitz with Max Hayward (Mariner Books, 1997). Copyright 1967, 1968, 1972, 1973 by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Excerpt from Es Geht Alles Vorueber, music by Fred Raymond, lyrics by Max Wallner and Kurt Feltz. 1942 by Edition Majestic Erwin Paesike. Used with permission.

PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS:

: Photograph by George Hoyningen-Huene.

Used by permission of R. J. Horst.

: Photograph by Heribert von Koerber.

Used by permission of Giv von Koerber.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

MacRae, Sigrid von Hoyningen-Huene.

A world elsewhere : an American woman in wartime Germany / Sigrid MacRae.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index

ISBN 978-1-101-63582-7

1. Hoyningen-Huene, Aime von, 1903 2. Hoyningen-Huene, Heinrich Alexis Nikolai von, 19041941. 3. MacRae, Sigrid von Hoyningen-HueneFamily. 4. Married peopleGermanyBiography. 5. AmericansGermanyBiography. 6. Aristocracy (Social class)Baltic Provinces (Russia)Biography. 7. Intercountry marriageHistory20th century. 8. Love-letters. 9. World War, 19391945GermanyBiography. 10. World War, 19391945RefugeesBiography. I. Title.

CT1097.H69M33 2014

943.0864dc23

2014004501

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

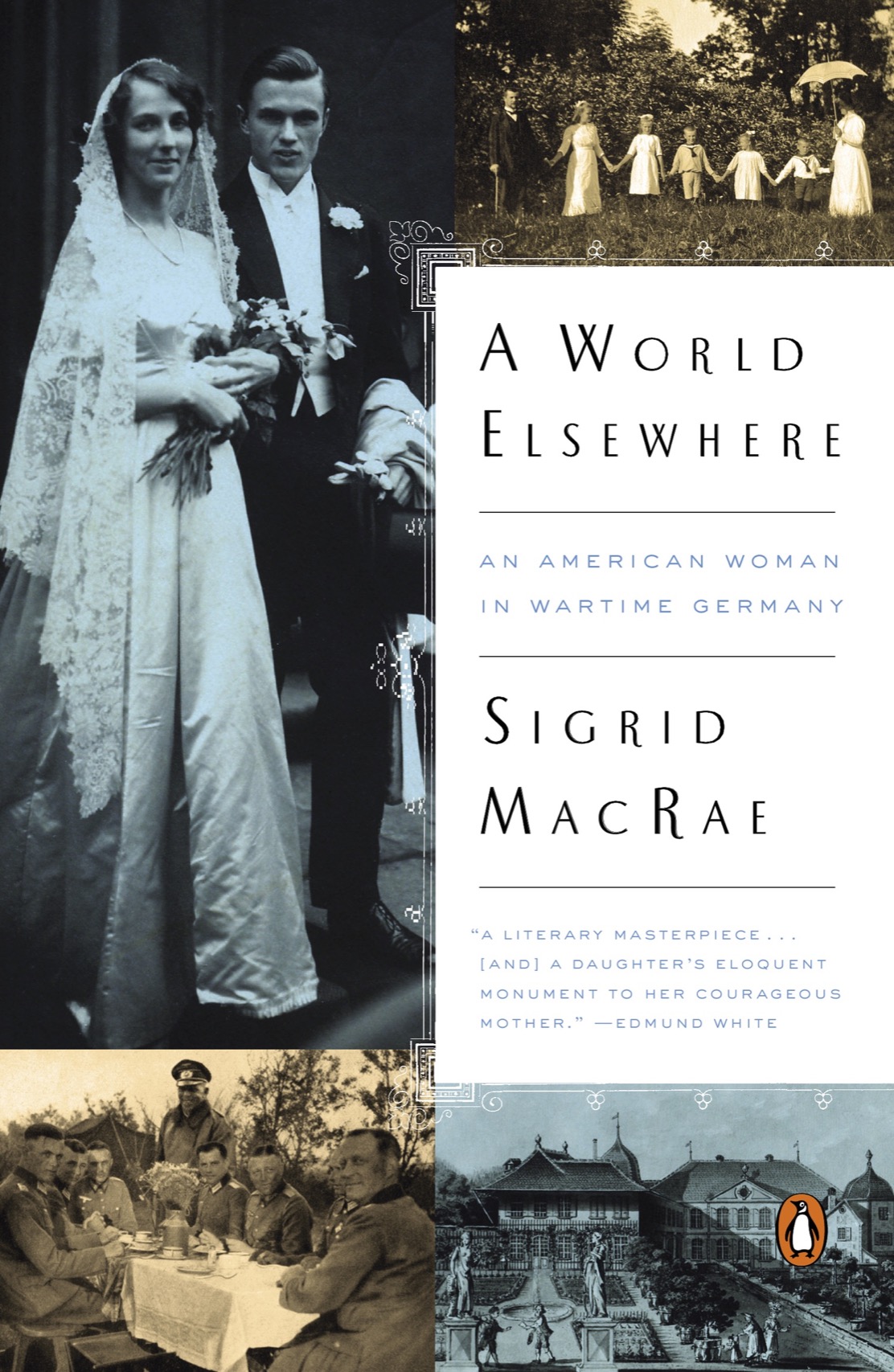

Cover design: Alison Forner

Cover photographs: (top left, top right, bottom right) Courtesy of the author; (bottom left) Photograph by Heribert von Koerber. Used by permission of Giv von Koerber

Version_2

To those who went before,

especially my mother, and to

those who will come after.

Prologue

T he box was beautiful. My mother had bought it in Morocco many years ago, and as a child, I admired it in secret, stroking the tiny pieces of mother-of-pearl inlay on the surface, its patterns conjuring faraway places. Its ivory keyhole held a key with a striped ribbon attached. Turning the key always produced a soft pling-plong, but never opened the box. After many decades, my eighty-five-year-old mother was tired of Maine winters and was moving to Arizona. Parceling out her possessions and the memories they held to her five surviving children, she now held the box out to me, saying simply, Your fathers letters.

I had always suspected that the box held them. Exotic and mysterious, it was the perfect receptacle for the treasured relics of a husband long dead and a father I had never known. It contained a chapter of my mothers life that she had closed long since, one I was reluctant to reopen. The moment was freighted with feeling; her expression suggested things that I was afraid I could respond to only with tears. Neither of us felt comfortable in such emotional territory, and we cut it short. I stowed the box tenderly in the car along with the other pieces of her life she had designated for me: a miscellany of books, pictures, rugs, silver. As the car pulled away, she stood, small and contained, the enormous firs by the garage dwarfing her as she waved good-bye. Behind her, morning sunlight skittered across the bay.

At home the box satstill beautiful, but still steadfastly, stubbornly lockedkeeping its secrets. Though my mother had given it to me, I felt that breaking this family reliquary open by force was wrong. Besides, I was reluctant to discover what the box held. Inside was the person who had changed the shape of my mothers life, whom my older brothers and sisters loved and remembered, a real person to everyone in the family except me, the youngest. For years his mythical presence had loomed large, but as an absencean immense absence. Time had gradually healed my mothers wounds, but I was wary of causing pain by asking about him. In fact, I realized that I bore some resentment toward the man I had held responsible for many miseries.

My mother had moved on, but for me he remained unfinished business. Opening the boxresurrecting himwould mean finding not only the man who became my father, but also the man responsible for the Nazi! a first-grade classmate had yelled at me as a six-year-old, newly arrived in the States from Germany. I didnt know then what that was, but whatever it was, I knew it wasnt good. The taunt stayed with me. It was thrown at me in many other guises, and eventually I blamed my father.

I always felt different growing up. My family was an anomaly in rural Mainea clan of outsiders. There was my unfamiliar, unpronounceable last name: von Hoyningen-Huene. Even just von Huene was bad enough; I longed to be Linda or Susan, Smith, Jones, or Brown. There was the language, and there was the taint of being German. And in spite of my mothers tireless efforts to always provide a beautiful place to come home to, my sense of dislocation never budged. There was nowhere that felt unmistakably like home.

My fathers parents, Baltic Germans exiled from Saint Petersburg to Germany after the Bolshevik Revolution, had suffered exile bitterly, feeling displaced, lost, and alienan awareness that also left an indelible mark on my fathers life. His younger sister once told me that the only place she ever felt homesick for was Saint Petersburg, a city she had last seen as a twelve-year-old, more than seventy-five years before. Such feelings and memories were endemic; they came with the territory, demanding the lions share of space in the exiles little bundle of belongings. Maybe for us, as for so many, they ran in the family.

My persistent hunt for home began long before my mother gave me the Moroccan box, and much of it circled around my father. He had always been a presence, if iconic, and I was hardly ignorant about him. His portrait hung in our living room along with one of my parents as a young couple in Paris in 1929, by a celebrated photographer cousin, George Hoyningen-Huene. Assorted forebears kept them company on the walls. I knew about his past; stories about him were family lore. There were letters, diaries, and poems from his turbulent early years. I had read his letters from France as an officer in Hitlers army, where an occasional passage sounding alarmingly like Nazi propaganda had made me squirm, yet his awareness of history, his wide learning, his sympathy for people, and his enviable optimism shone from every page. His brief diary from the Russian front had also made me question what his being in Hitlers army really meant. Still, for me, he remained buried in the uneasy murk of history.