VICTORIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Victoria University of Wellington

PO Box 600 Wellington

vup.victoria.ac.nz

Copyright Helena Winiewska Brow 2014

First published 2014

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers

National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Winiewska Brow, Helena.

Give us this day : a memoir of family and exile / Helena Winiewska Brow.

ISBN 978-0-86473-968-1

1. Winiewski, Stefan. 2. Winiewska Brow, Helena.

3. Refugee childrenPolandBiography. 4. Refugee children

New ZealandBiography. 5. World War, 1939-1945RefugeesPoland.

6. World War, 1939-1945RefugeesNew Zealand. I. Title.

305.906914092dc 23

ISBN 978-0-86473-968-1 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77656-008-0 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-77656-009-7 (Kindle)

Ebook production 2014 by meBooks

To my parentsStefan and Olga Winiewski

Authors Note

The geographical and historical breadth of this story means that it crosses many boundaries of language and place. Polish, in particular, can appear daunting on the page to English-speaking readers, while shifting borders and political regimes in Eastern Europe and Central Asia over the last century have meant that many place names have changed, sometimes more than once. The following notes explain why I have used particular names and spellings, and clarify instances of Polish pronunciation.

Place names

Where possible, I have used place names appropriate to the storys chronology in this text. For example, the pre-war Polish town of Brze becomes Brest following its Soviet takeover in 1940. Similarly, particularly in Central Asia and Iran, Ive generally used the place names and spellings that my father was familiar with at the timethough many of these have since officially changed. In some cases, hazy and traumatic childhood memories have complicated this process; some places remain necessarily nameless.

Personal names

Poles use informal diminutive first names among friends. Different diminutives have different emotional connotations, ranging from neutrally friendly to strongly affectionate. The Polish family members and friends in this book are named as I knew themfor example, my uncle was never Kazimierz to me, but the less formal and more friendly Kazik, just as my aunt was always Hela, never Helena. Surname endings, similarly, sometimes differ to indicate gender. Winiewski, for example, is the nominative form for a male in my family; Winiewska is the form for a female. Some female family members now living in New Zealand, however, have chosen to simplify matters by using the male nominative form only.

Pronunication

Polish pronunciation is not as difficult as it looks and follows regular rules (for example, emphasis is almost always on the penultimate syllable). But for the occasionally complex-sounding names and words used in this text, here are some phonetic soundings and, where appropriate, English meanings.

Alicja/Alinaah-leets-yah / ah-leen-ah

Basiabah-shah

Czesaw/Czesiekches-wahf / ches-shek

Izabela/Izaee-zah-bellah / ee-zah

Jozefyuw-zef

Kazimierz/Kazikkah-zheem-yesh / kah-zhick

Marysiamah-ri-shah

Regina/Reniare-gee-nah, ren-yah

Wacekvaht-sek

Winiewski/Winiewskavish-nyev-ski / vish-nyev-skah

Wojtekvoi-tek

Zbigniewzbeeg-nyef

Brzebzhests

Krkwkrah-koov

Wrocawvroh-swahf

CiociaAunty, choh-chah

DziadzioGrandad, jah-joh

Dzie dobryhello, jen-dob-ree

Dzikujethank you, jen-koo-yeh

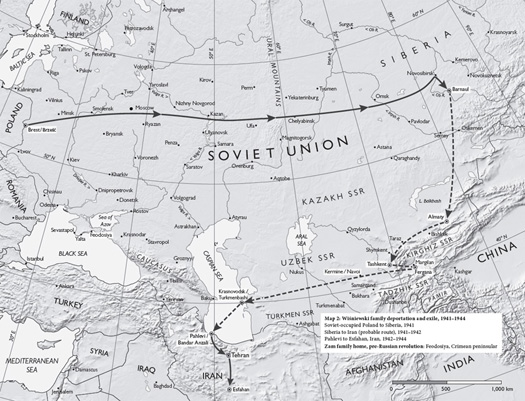

Map 1: Polands territorial losses and gains, 1945

Winiewski family home, pre-World War II: Brze and surrounds

(Maps by Geographx Ltd)

This place where you are right now,

God circled on a map for you.

Hafiz

Prologue

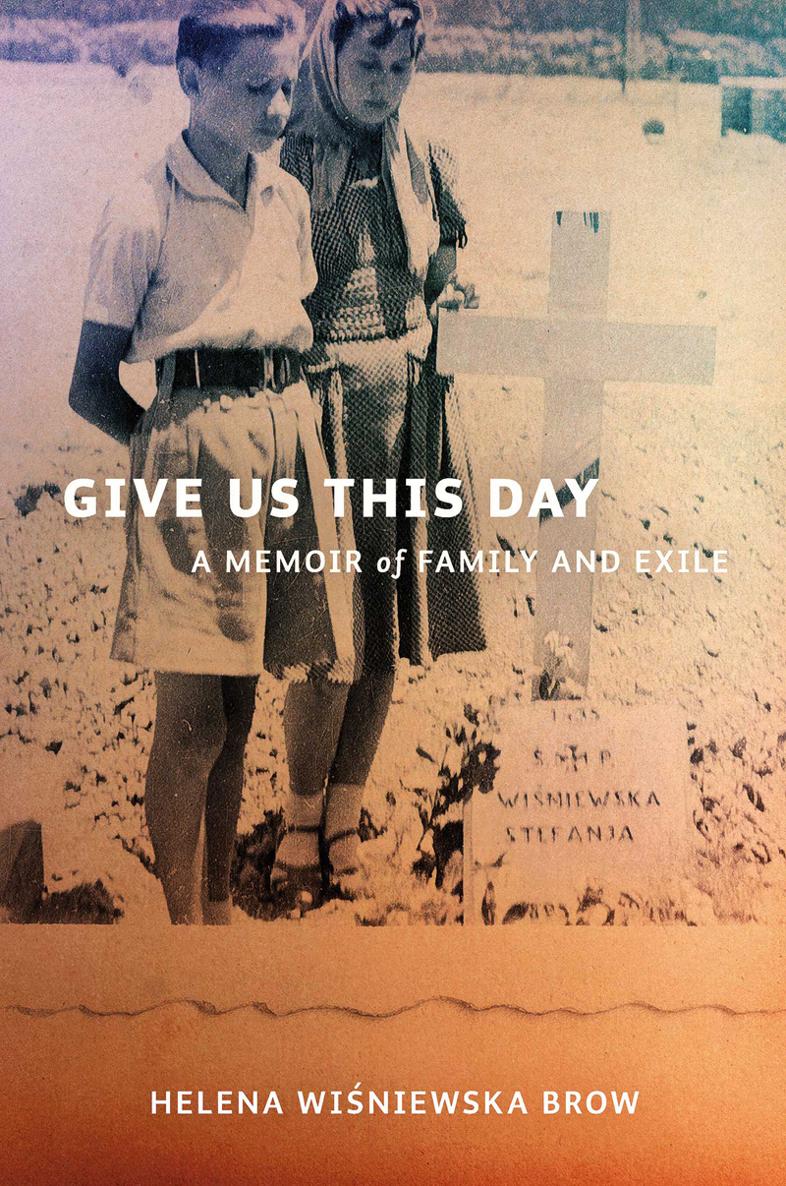

Neither of them is looking at the camera.

Hela, my fathers sister, stands behind the makeshift wooden crucifix, a cotton scarf tied under her chin. In Mary Jane shoes and white ankle socks, she doesnt look her 19 years. Next to her, my father, 14-year-old Stefan, is bare-kneed and in oversized shorts. His eyes, lowered, are fixed on the fresh and dusty grave at his feet.

Its June 1944, and the grave is my grandmothers. A week before this photograph was taken, 49-year-old Stefania Winiewska was buried without ceremony in the Polish corner of Tehrans Catholic cemetery. These two children, the only family members then aware of her death, had travelled north from the Iranian city of Esfahan in the back of a canvas-topped army truck to say a belated goodbye. For Stefan, whod had no idea his adored mother was so sick, no idea shed even come to Tehran for surgery, this evidence, a heaped mound of recently turned rubble, is scarcely believable.

The photograph of their visit is a black-and-white souvenir of his bewilderment. Today it sits in an album with yellowed pages, some of them empty, that my father keeps in an old-fashioned suitcase with flick-up clips. He has few photographs of his early years, certainly none from before the war, so this is perhaps the youngest image of him I will see, probably the saddest.

Here is the end of your mother, it says. Here is the end of your world.

Dad has to bend to put his case of photographs away, his square fingers fumbling with the low cupboard handle. It seems Im interested in the kind of detail that he either cant or wont recall. Who arranged the truck for them? Who took the photo? How long did they stay in Tehran? He cant remember any of those things, he says.

You know, I ended up in hospital the day after this photo. I had malaria, he tells me. When I got off the truck back in Esfahan I didnt know where I was. I hardly remember being at the cemetery that day.

Im asking because Ive never seen this image before. Not much more than a year ago, I stood with him at that same grave in Tehrans eastern suburbs, just as his older sister once did. The cemetery looked different when I was there, of course. The dust and rubble had been tidied away under blankets of concrete and strips of grass. The old brick walls that still lined the cemeterys perimeter, separating its Catholic foreignness from the rest of that Muslim city, were hidden behind veils of green foliage. Maybe thats the way my father prefers to remember his mothers death, I think: the rawness gone, a loss smoothed by time. Maybe its just me who sees it as a terrible turning point in the movie of his life, time rewinding like a clacking reel of film, frame by frame, back to that graveside vignette. My grandmothers death sent the lives of her children, lives already way off course, spinning in an even less familiar direction. For my father it was a trajectory that would end here, 70 years later, in a country on the wrong side of the world, in a carpeted townhouse in a city of foreigners.