First published in 2012 by

Turning Stone Press, an imprint of

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

With offices at:

665 Third Street, Suite 400

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.redwheelweiser.com

Copyright 2012 by Jadz Morrison

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-61852-040-1

ISBN (hardcover): 978-1-61852-039-5

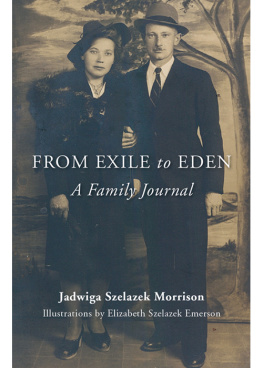

Cover design by Jim Warner

Printed in the United States of America

IBT

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

This book is dedicated to the memory of Tadeusz and Helena Szelazek... two of the most extraordinary individuals I have had the privilege of being related to.

Contents

Part I

The Ancestry, Legends, and Early Memories of the Szelazeks

1

November 20, 1918 Biala Podlaska, Lublin County, Poland

S aints Peter and Paul Cathedral in Lublin was as cold inside as it was outside, but the small crowd attending Helena Semerylo's christening was too focused on the happy event to think about the cold. The priest had just entered the date of birth on her baptismal certificate as November 20, 1918. It didn't matter that she was actually born on the 11th of November; many people used their baptismal date as their birthday. Lately, not many official birthdates were being registered in her county anyway. The war was the reason. So many towns were being burned to the groundgovernment buildings, records, and all.

Helena was born in the nearby village of Biala Podlaska (which translates to White Village near the Forest) where beautiful forests of white birch lined the road to town. These forests were now protecting all their loved ones. out of these woods, the Polish Resistance continued their forays against the Austro-Germans who were moving through their villages and towns.

Helena's mom, Aniela, stood at the baptismal font and thought about the events of the past week. The fear she experienced would be permanently etched upon her memory. German soldiers were prowling through their village, ransacking their homes, and stealing all the supplies and food they could find as they slowly retreated back across Poland. This same scenario was being played out all over the country. The Central Powers were losing the war and the Austro-Germans were preparing to move their forces back. It was rumored that Charles the First, the last Hapsburg emperor, had abdicated on November 12th. That was the day after Helena had been born and it was also the day on which an Austrian soldier rounded up all the ducks and geese on the Semerylo property. The livestock and fowl were all the family had to keep them fed that winter. They would all certainly starve if no one stopped the looting.

That night, the commotion outside the farmhouse woke Aniela, who was alone with her new baby. Her husband had left earlier that day, at dawn, to go back into the forest to join the other Resistance fighters. Aniela slipped out of the house, leaving the one-day-old child sleeping in her crib. Unnoticed, she ran to the side of the house where a soldier had temporarily left the trussed birds. He was busy foraging through their barn, so he did not see her as she quickly cut the ropes that bound the fowl. She shooed the ducks and geese onto their large pond, hoping that it would be impossible for the soldier to retrieve the frightened birds from the water. This done, Aniela ran back into the house. As she lay on the bed with the baby next to her, her heart pounded from exertion and from the risk she was taking. The Austrian soldier soon became aware of what had happened to his loot. He burst into the bedroom, and as he pointed a gun at her, he cursed at her in a variety of languages.

It was you who released the birds. I should kill you. If it weren't for this little baby next to you, you'd be dead. If I killed you, she'd die as well; and I don't kill babies. You should thank her for your life because she's the only reason you're still living!

In the church, as she remembered this terrifying night, Aniela did thank God for being alive, for her two daughters, and for her husband Wladyslaw. God had been watching over them a lot lately. The Austro-German soldiers had nearly caught Wladyslaw on several occasions. He was a commandant in the Polish Volunteer Army (Polska Ochotnicza Wojskoit was this army that later pushed back the Bolsheviks as they tried to take over eastern Poland). The battles in Poland never seemed to end; just living was a constant battle for the Polish people. If it wasn't war, it was starvation, or sickness, and Aniela was weary of it all.

On this day, the whole Semerylo family was in the church, attending the christening of Helena. The officiating priest wasn't the one Aniela had expected to perform the service. They had requested Father Sliwonji, who was a relative of hers, but he had recently been executed by the Austro-German soldiers for spying.

Father Sliwonji had been in the church bell tower, with binoculars, watching the advance of the soldiers, and he had sent word to the Polish Resistance of the enemy's location. Unfortunately, the Germans had seen a glint of light reflected from his binoculars as he hid in the tower. When they could find no other people in the church, the Germans dragged him out and shot him. They hadn't seen the man running toward the forests with news of the German approach. The civilians had been warned and the Resistance was ready.

In the cathedral, everyone spoke in hushed voices, remembering the many good deeds of the brave priest. When they prayed that day, they prayed for him as well as their own families. Father Sliwonji met his end with courage and defiance. His parishioners, in this small ravaged town, wondered if they would also meet the same fate as the war dragged on.

2

November 20, 1918 Stannowo, Nieszawa, Warsaw County, Poland

H is breath left steamy gray circles on the glass panes as he looked out on the gardens ravaged by frost. Those once fragrant, gloriously brilliant blooms and luxuriant bushes were now dark, blighted ruins. No longer did anyone stop to stare in amazement, as they had this past summer when everything had been a wild mass of color. There were so many unusual plants growing in their ornamental gardens; plants that some people had never seen beforeexcept in books. The little boy drew circles on the steamy cloud covering the window. He dreaded the coming of winter, which was already leaving its mark on the flowerbeds. His mother, Antonina Zalewska Szelazek, had lovingly planted the gardens years ago, and they had been a constant source of joy for her. Not that there was much joy these days, what with the war dragging on the way it had. And what a war it was! So many people dead, so much damage and suffering!

Why are some people calling this the Great War, father? the boy asked.

His father looked up from the ledgers on his desk.

Maybe it is a great war, but it's just another war for the Polish people. It seems that wars in Europe always involve us in some way. Don't you have anything to do, Tadeusz, besides asking me questions all morning long? I've never heard a more talkative nine-year-old. Your brothers and sisters can answer your questions. Go bother them.

Next page

1

1