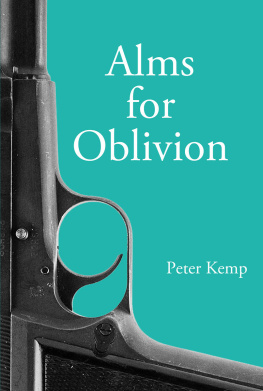

No Colours or Crest

Peter Kemp

Copyright 1958 Peter Kemp

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 9798654735744

v. 1

First ebook edition by Mystery Grove Publishing Co. LLC

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY BROTHER NEIL

14th July 191010th January 1941

NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER

First published in 1958, No Colours or Crest is legendary British adventurer Peter Kemps follow-up to Mine Were of Trouble, which detailed his combat during the Spanish Civil War. The book recounts Kemps service with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War in Europe. While readers of his first book got to see Kemp as a brave but nave volunteer in the fight against communism, his second is more complex. Kemp begins the war as a commando, but soon becomes a spy trapped in a labyrinth of alliances and betrayals. The threat posed by the Soviets is often far more immediate than that from the Axis. This is not the Second World War you see in the movies.

The book is a firsthand account of the conflicts underbelly, written by a man whose character, bravery, and patriotism is above reproach. Despite its value, No Colours or Crest was out-of-print more than 60 years, with the few surviving copies too expensive for the average person. Mystery Grove Publishing Company is happy and proud to finally make this classic available for the first time ever in paperback and ebook form, allowing Kemps work to be enjoyed by a new generation of readers.

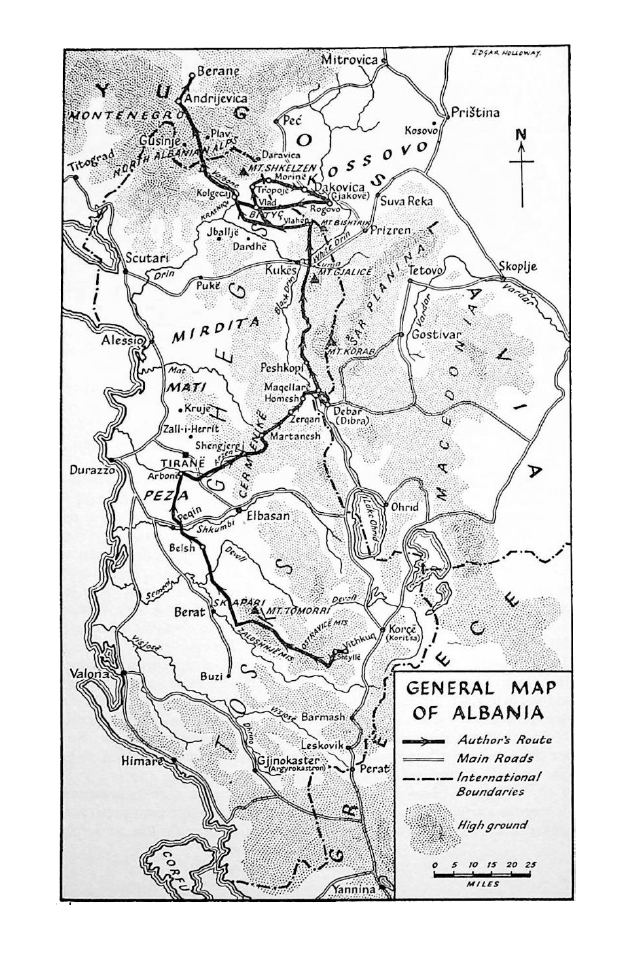

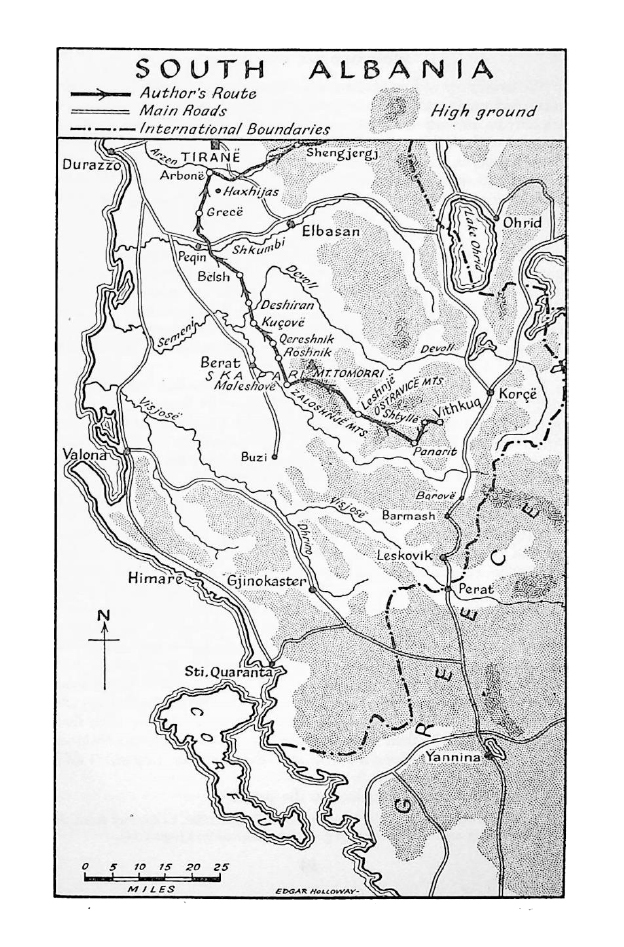

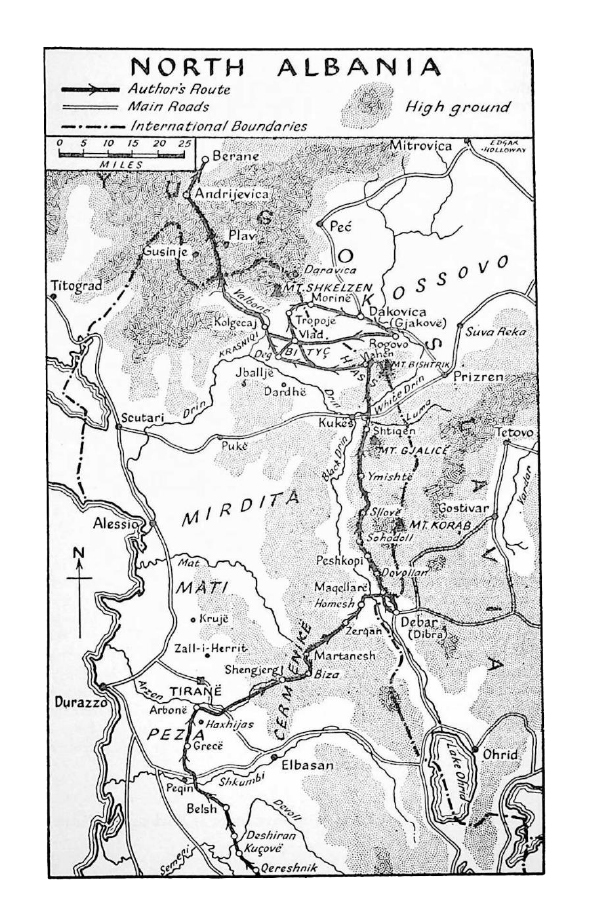

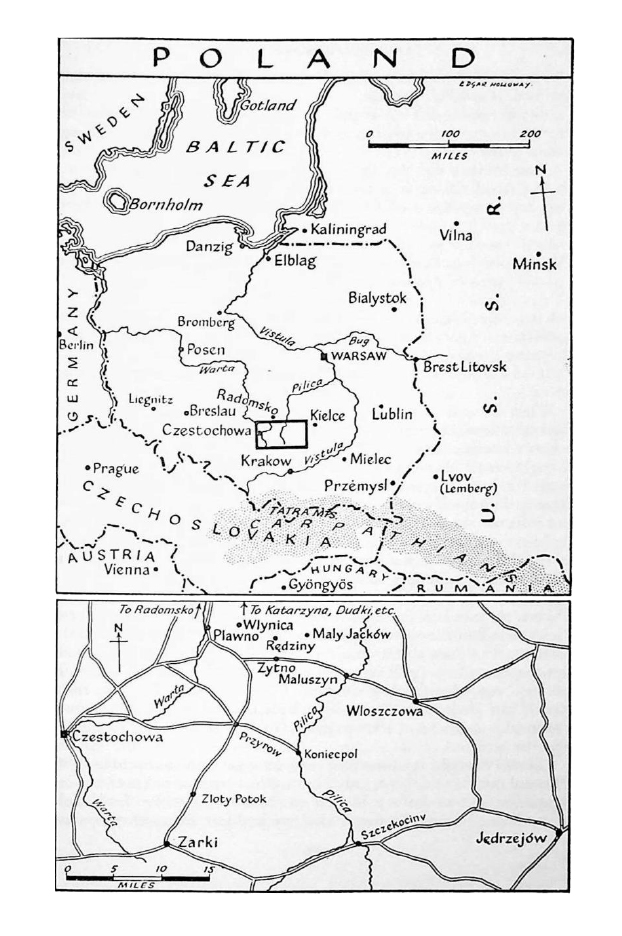

Please note, although weve attempted to recreate Kemps work, several photographs appeared in the first edition hardback that would have been too costly to reproduce while keeping prices low. These photos are available free of charge on our Twitter account (@MysteryGrove). Furthermore, the maps of Kemps travels, originally scattered throughout the first edition, have been consolidated at the front of this book for readers convenience.

We are very grateful for the enthusiasm with which our earlier releases have been received. We hope to make similar lost or rare titles available to a wide audience in the near future. Please follow us on Twitter for information about our upcoming releases and other news.

Thank you for reading!

Special acknowledgment goes to the men of the HWGC, CL, and Grove Street, along with JAM. Without their support and friendship these releases would not be possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My particular thanks are to Colonel David Smiley, M.V.O., O.B.E., M.C., some of whose photographs are reproduced in this book; Commander Alastair Mars, D.S.O., D.S.C., R.N., and his First Lieutenant Mr. A. G. Stewart, for their reading and criticism of the passages dealing with my experiences in H.M. submarines; my friend Ihsan Bey Toptani for much valuable help on the chapters concerning Albania; Captain A. R. Glen, D.S.C., R.N.V.R., and to Mr. I. S. Ivonovi, aboard whose cargo boats I have done most of my writing; and to the many kind friends, too numerous to mention, who have helped me with their advice, encouragement, and criticism.

PETER KEMP

Theres a Legion that never was listed,

That carries no colours or crest,

But, split in a thousand detachments,

Is breaking the road for the rest.

Rudyard Kipling

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Of course they must let you wear your Spanish Civil War medals, pronounced my uncle in the brisk, cheerful tones that generations of Indian Army subalterns had learnt not to contradict.

After all, the whole point of campaign ribbons is to indicate that the wearer is a veteran who has seen active service.

Seated erect in a hard, high-backed chair, with his long, thin legs sprawled wide in front of him, my uncle quizzed me with bright, twinkling eyes; his head was cocked to one side, his deep-lined bony face creased in the half mocking, half affectionate smile that had at once charmed and disconcerted his Sepoys, his relations, and refractory Frontier tribesmen. My gaze wandered round the bleak sitting-room of the suite in the small hotel near the Brompton Road where he had moved when the approach of war drove him from the sunny comfort of the Italian Riviera: plain, deep red carpet; green, flowered wallpaper; drab chintz-covered sofa and armchairs; white net curtains drawn back from the windows to give a dispiriting view of the grimy, uneven Kensington skyline. The street outside was silent and heavy with the gloom of that impending catastrophe which before the end of the next year was to obliterate this unpretentious little family hotel from the face of London.

It was the morning of Sunday, 3rd September, 1939. Germany had invaded Poland; Britain and France had sent an ultimatum to Hitler; King Carol was digging a ditch round Rumania. Within an hour we should hear the sad, tired voice of the Prime Minister announce the beginning of another world war.

A month previously I had returned to London after nearly three years service in Spain, one of the very few Englishmen to fight in the Nationalist armies, defending a cause which enjoyed little popularity among my countrymen. I had joined the Nationalists almost immediately after coming down from Cambridge, partly out of a desire for adventure and partly from the conviction, fostered by the study of early, uncensored reports from newspaper correspondents on the spot, that the vital issue of the civil war was Communism, and that a Republican victory would lead to a Communist government in Spain. A strong Tory myself, I had served in the Carlist militia and the Spanish Foreign Legion, where my friendsTraditionalists, Conservatives and Liberal Monarchistshad no more sympathy than I for totalitarian regimes. But General Francos friendship with Hitler and Mussolini and his establishment of the Falange as the only political party in Spain had erased from most British minds all memory of the Communist threat he had defeated; even the Soviet-German Pact had not wholly revived it.

Now the weight of Republican propaganda, backed by the formidable organization of European Communism, had dubbed Franco a Fascist, while many of my British friends regarded me as, at best, a Fascist fellow-traveller. Even those who sympathized with me feared that Spain would enter the war against us, although I had seen enough of the devastation and war-weariness there to believe that she would remain neutral.

When I had left England for the Spanish Civil War, with all the romantic enthusiasm, ingenuousness, and ignorance of my twenty-one years, I had never imagined that six months after it was over I should find myself involved in another and infinitely vaster holocaust. Now, without thinking of myself as a veteran, I knew enough of war to feel no elation at the prospect; I was conscious only of a grave anxiety at the strength of the forces matched against us, a grim realization of what defeat would mean, and the hope that the experience I had acquired in the face of much disapproval and ridicule might not prove entirely useless to my country.

I left my uncle to go to his club in Pall Mall, and sauntered morosely through dismal, deserted streets to the house in Brompton Square which an aged great-aunt had lent me while she and her husband relaxed in the milder atmosphere of Brighton. Greta, the amiable young Austrian cook, panted upstairs from the kitchen, her plump, round peasant face split in a wide, careless grin.