In loving memory of R.O.

PROLOGUE:

How I came to this

don't know if we can ever truly atone for our sins. I once thought it was absolutely the case. God knows I've spent enough years trying to do so. My friend Henry's death silently hung over me for much of my childhood, but I'd finally begun to heed my mother's advice to "let sleeping dogs lie." Then came the night of March 15, 2000.

don't know if we can ever truly atone for our sins. I once thought it was absolutely the case. God knows I've spent enough years trying to do so. My friend Henry's death silently hung over me for much of my childhood, but I'd finally begun to heed my mother's advice to "let sleeping dogs lie." Then came the night of March 15, 2000.

We were living in Queens: my then wife, my two-year-old daughter, and I. It was quite a haul for my wife and me from Highland Avenue in Jamaica to our jobs, mine in Chelsea, hers in Harlem, but it was worth it if it meant living in a neighborhood that was peaceful and quiet. Emotionally, things were anything but. Henry's death had come roaring back into the forefront of my thoughts thanks to my daughter's near death from a bout with febrile seizures. My child's mortality was a constant concern, but despite these and other distressing matters, I kept my inner anxieties a secret even from those who were closest to me. Unfortunately, it had become common practice for me to withdraw and become more solitary when I felt emotionally overwhelmed.

That was, until Patrick Dorismond's unlikely death at the hand of New York's finest. If you lived anywhere other than New York City in 2000, you've probably never heard of Patrick Dorismond, but in the then shaky tenure of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Dorismond became an exclamation point in a long chain of police brutality cases that began with Abner Louima in 1997.

Unlike Louima, the well-known Haitian immigrant who was sodomized with a plunger by several police officers and became a national name thanks to the involvement of flamboyant personalities such as Al Sharpton, the Dorismond case was much lower profile. But for me, the Patrick Dorismond incident was the single most important case of political misconduct in the city's history. His experience caused me to think for long hours about atonement, and is the primary reason I decided to tell my story.

Pre-September 11 New York was a time when Giuliani's zero-tolerance policies toward crime had made the city the safest it'd been in decades-but simultaneously put the mayor and the police force at odds with almost all of New York's minority ethnic communities. Claims of civil rights violations ran rampant, and it seemed as though every week the mayor had to hold a press conference to explain away some new misdeed.

Patrick Dorismond was the twenty-six-year-old father of two young children, and he had aspirations of becoming a police officer. At the time, he was working as a security guard in Manhattan. Dorismond and a friend stopped the night of March 15 at a bar for a beer after work, and were approached by an undercover police officer posing as a drug dealer. It was part of an elaborate sting operation called "Operation Condor" that was rooting out potential narcotics customers, and had already netted more than eighteen thousand arrests in only two months.

The operation's premise is simple. The undercover officer simply approaches a person in one of the designated areas and attempts to sell him drugs. When the person agrees and tries to make the purchase, he's arrested on the spot. However, things did not go according to plan when the undercover officer approached Dorismond. Rather than agree to the deal or just ignore the dealer, Dorismond became enraged, and here the testimonials differ. According to police, Dorismond struck the officer. Several witnesses at the scene claimed that the undercover cop was the aggressor. Nonetheless, when the smoke cleared, Patrick Dorismond lay dead, shot by the police for doing something any suburban parent would be saluted for: confronting a drug dealer.

Of course this was a terrible public relations blunder for an already embattled mayor. Police had only recently been acquitted for unleashing a fusillade on unarmed immigrant Amadou Diallo when they mistook his wallet for a weapon, and this was yet another sign that the policies of the department and the mayor himself were too cavalier in distinguishing between black criminals and black citizens. Dorismond was not a career criminal. His record was clean. In fact, it was so clean that the administration had to dig into his juvenile record to find any transgressions whatsoever. As it turns out, Dorismond had been arrested for robbery in 1987, when he was only thirteen years old. The mayor claimed in front of a press assemblage that Dorismond "was no altar boy"-insinuating, without saying it, that Dorismond had his fate coming.

This guy was no altar boy. The interesting irony that Dorismond was indeed an altar boy as a child was overshadowed by the fact that his charge of assault as a teenager made him a career criminal in the eyes of many. It didn't matter that this happened during his teenage years, that the arrest reportedly came as the result of a fistfight over a quarter, or that the record of his transgression was supposed to have been sealed and then expunged when he turned sixteen. It didn't even matter that his death came as he was trying to do the right thing -the exact thing many a public service announcement has urged us to do. When Patrick Dorismond was gone, he became another dead nigger with a record.

It was disheartening. It was enraging. If this man was no altar boy, then I was the anti-Christ. Hadn't I done enough good to deserve not to have my entire life encapsulated by that single event? I hadn't touched a gun since that afternoon back in 1988. I'd never touched an illegal drug. I didn't even drink (back then). I did everything I could at every turn to help others. Did any of it matter?

The short answer was, at least in some eyes, no. And the sobering dose of that reality depressed me. I could one day unwittingly find myself on the receiving end of some misunderstood person's knife, bullet, or worse. If that happened, would the people having those postmortem conversations describe me only as a juvenile felon? Given, what I did was absolutely indefensible. But at least I'm going to have a voice in the single event that may one day come to encapsulate my life. At least I'm going to have a voice if people decide to hold a discussion about the Shooting.

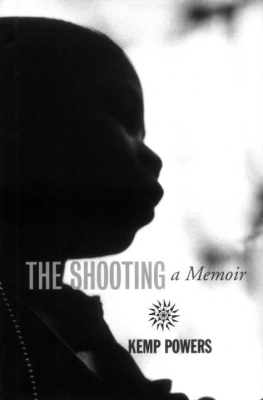

hen I was fourteen, I shot my best friend in the face and watched him die. I'm not trying to sound cold when I say it like that. I'm not a criminal, at least not to the people who matter. Not to my family. Not to his family. Not to my friends. Not even to the state of New York. Still, just typing these words shocks me; I see them taking shape across the screen and I can't believe the actions I'm describing are my own. In the fifteen years since it happened, I haven't discussed the incident in detail with a single person.

hen I was fourteen, I shot my best friend in the face and watched him die. I'm not trying to sound cold when I say it like that. I'm not a criminal, at least not to the people who matter. Not to my family. Not to his family. Not to my friends. Not even to the state of New York. Still, just typing these words shocks me; I see them taking shape across the screen and I can't believe the actions I'm describing are my own. In the fifteen years since it happened, I haven't discussed the incident in detail with a single person.

don't know if we can ever truly atone for our sins. I once thought it was absolutely the case. God knows I've spent enough years trying to do so. My friend Henry's death silently hung over me for much of my childhood, but I'd finally begun to heed my mother's advice to "let sleeping dogs lie." Then came the night of March 15, 2000.

don't know if we can ever truly atone for our sins. I once thought it was absolutely the case. God knows I've spent enough years trying to do so. My friend Henry's death silently hung over me for much of my childhood, but I'd finally begun to heed my mother's advice to "let sleeping dogs lie." Then came the night of March 15, 2000.

hen I was fourteen, I shot my best friend in the face and watched him die. I'm not trying to sound cold when I say it like that. I'm not a criminal, at least not to the people who matter. Not to my family. Not to his family. Not to my friends. Not even to the state of New York. Still, just typing these words shocks me; I see them taking shape across the screen and I can't believe the actions I'm describing are my own. In the fifteen years since it happened, I haven't discussed the incident in detail with a single person.

hen I was fourteen, I shot my best friend in the face and watched him die. I'm not trying to sound cold when I say it like that. I'm not a criminal, at least not to the people who matter. Not to my family. Not to his family. Not to my friends. Not even to the state of New York. Still, just typing these words shocks me; I see them taking shape across the screen and I can't believe the actions I'm describing are my own. In the fifteen years since it happened, I haven't discussed the incident in detail with a single person.