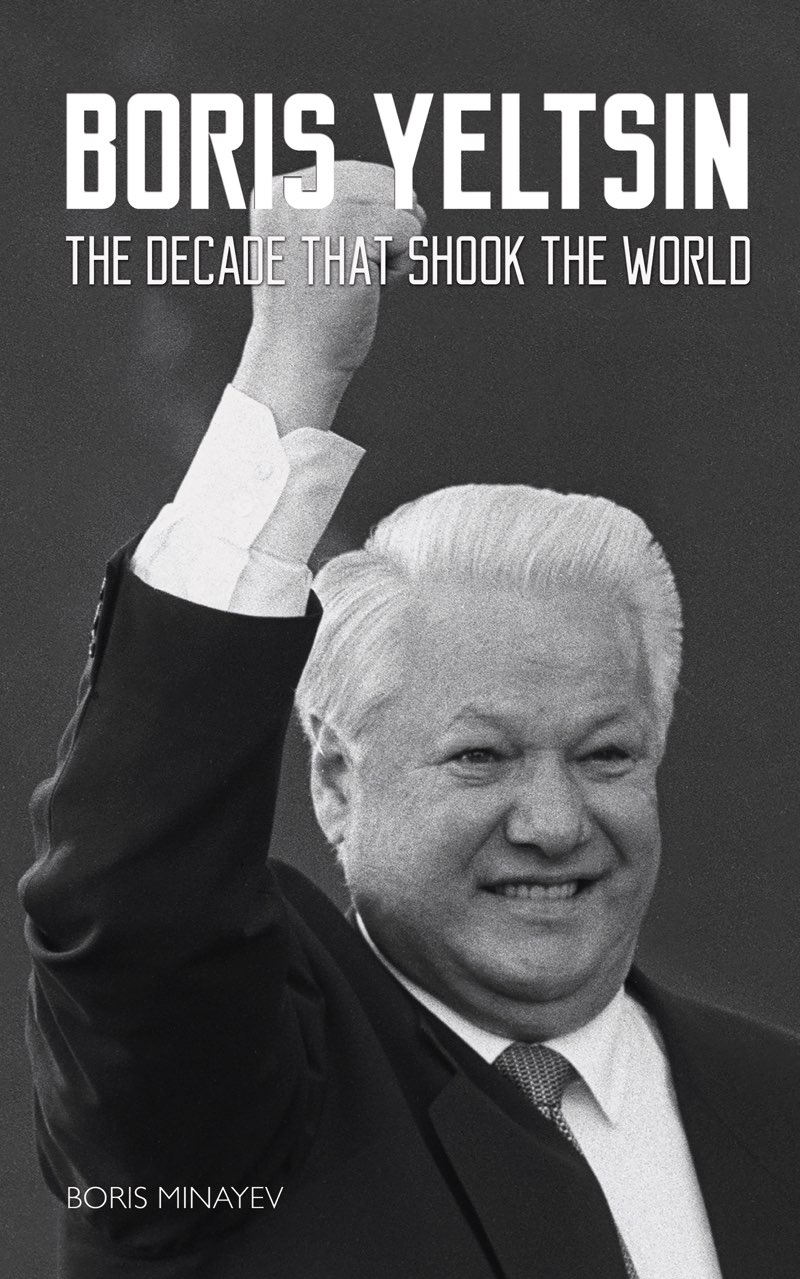

Boris Minaev - Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World

Here you can read online Boris Minaev - Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Glagoslav Publications, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World

- Author:

- Publisher:Glagoslav Publications

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

B oris Yeltsin : The Decade that Shook the World

by Boris Minaev

Translated by Svetlana Payne

2014, Boris Minaev

Published with support of The Foundation of the First Russian President B.N.Yeltsin

2015, Glagoslav Publications, United Kingdom

Glagoslav Publications Ltd

88-90 Hatton Garden

EC1N 8PN London

United Kingdom

www.glagoslav.com

Published with support of The Foundation of the First Russian President B.N.Yeltsin

ISBN: 978-1-78437-924-7 (ebook)

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

T he literature on Yeltsin is vast. Memoirs have been produced not only by politicians first-hand participants in the events, Yeltsin himself penned three volumes of recollections but also assistants, press secretaries, political analysts, journalists, MPs, retired members of Gorbachevs Politburo, public figures now long forgotten, generals of special services and security service staff. I started working on Boris Yeltsins biography when he was still alive. I hoped he would read my manuscript but I did not make it in time. In my work I have used not only publicly accessible documents that have been printed or made otherwise accessible but also interviews that are published for the first time. I have received huge help and support from my friends, my journalist colleagues and Boris Yeltsins family, particularly the series of interviews with his wife Naina and daughter Tatiana, for which I am deeply grateful.

T here is no question of a direct legacy of religious traditions in the Yeltsin family, even though Yeltsins grandfather, Ignaty, had been a parishioner, along with everybody else in his neighbourhood, of a regular Orthodox church, the one in which Boris Yeltsin was later baptised. It is more a question of inheritance received indirectly, as a persistent theme in Russian life.

Yeltsins family tree had one particular characteristic, however his forefathers had never been serfs. Or to be more precise, they were never manorial property, and had never been owned by any individual. In the Urals, including the areas that the Yeltsins had come from originally, peasants had been mostly state-owned, which means they did have a master but it was not a lord of the manor but a clerk. The clerks responsibilities included collecting taxes or dues to the state, in the form of peasant labour. Another important characteristic was that such peasants had an option of buying their manumission and they could do so of their own free will.

At the same time this world had its own periphery, too: husbandmen, labourers and craftsmen. All of this was completely interdependent, guided by its own internal unwritten laws, and most importantly by a shared destiny, a common existence from which it was inconceivable and impossible to escape.

However, a state-owned peasant existed outside this self-contained world. He was, of course, also expected, on seeing a landowner, to bow and take his hat off but with him it was different: he did not believe passionately in the sacred nature of the established order of things, he was simply doing what was required. He was independent but equally he couldnt rely on anybody else, only himself. His immediate owner, the state, was too far away.

The history of Yeltsins family is a graphic example of how the Soviet era dealt with those who were independent by nature and inclined to rely not on the society, and thus swim in the allotted stream, but to be self-reliant. Both of Yeltsins grandfathers Ignaty Yeltsin, on his father Nicolais side, and Vasily Starygin, the father of Klavdia Starygina, his mother were middle-ranking peasants in the Urals. Their farms would have been relatively substantial. The collectivisation in the 30s was designed to target just such farmsteads.

Ignaty Yeltsin, along with his four sons owned a mill. Ignatys sons modernised the tiny village mill and increased its capacity with additional millstones bringing their number to a total of seven. Each son had a horse as well as some cows, sheep and other livestock. At harvest time, the Yeltsins were hiring additional help in the village.

Vasily Yegorovich Starygin, Yeltsins other grandfather, was a skilled wood worker, a carpenter and a cabinet-maker. He built houses, in the traditional Russian fashion. His wife, Afanasia Starygina, was the best-known dress-maker in the village that was sewing clothes for the entire neighbourhood.

However, back in the thirties, Vasily Starygin wasnt as wealthy as Ignaty Yeltsin. His sin before the Soviet power lay elsewhere; when building houses, he would hire seasonal workers and thus, according to Marx, Engels and Lenin, he was an exploiter.

Both grandfathers had to pay the price after 1930.

Cattle, the mill and the threshing machine all this was confiscated, taxes charged and paid in arrears and Grandfather Ignaty was deported to Nadezhdinsk (now Serov) in the north of the Urals. The new people who had had a hand in their dekulakisation would later go round sporting their confiscated clothes. The chairman of the village Soviet lived in their house. And what were the charges? It was being owners of the mill that had been servicing the entire village!

In the summer, the dispossessed Yeltsin brothers, who had stayed on in the family home in Basmanovo, were forced to repair the machinery that previously had been theirs: the mill and the thresher, although now it all belonged to the kolkhoz(collective farm).

Ignaty and his wife Anna lived in a dug-out hut, on short commons, in Nadezhdinsk for Ignaty no longer could work at the lumber-mill; he had been stripped of all his worldly possessions and started losing his eyesight. At 61 years of age, former miller Ignaty Yeltsin, Boris Yeltsins grandfather, died defeated, blind and exhausted. The year was 1936 and his grandson was five years old.

Meanwhile, two of Ignatys sons, brothers Nicolai and Andrian Yeltsin, came to realise that for them, branded with the anathema of having been dispossessed as kulaks, there was no life in Basmanovo, at least not in the nearest future with no way of providing for their families. In 1932, both brothers, having obtained the permission from the chairman of the kolkhoz, left for a construction project in Kazan

It was the Aviastroi a huge aircraft plant that would become the pride of the Tatar capital city and the flagship of its industry. It would be the first to manufacture military aircraft and the famous Tupolev jetliners, TU-104. At this point, however, Aviastroi was just a huge greenfield site, a construction pit teeming with workers wheeling barrows and where they lived in ramshackle huts.

Construction, however, spelled rescue, being at the same time both hard labour, as ever in Russia, and their only solution. All through the 20th century, the territory of the former Russian Empire had been a scene of transmigration with the titanic shuffling around of huge and diverse groups of the population. Even in the more humane years of the Khrushchev era, when the long-awaited exonerations suddenly became a reality and crowds of released convicts headed homewards from the camps, even then huge numbers of people would move from their native towns and cities to Kazakhstan, to develop the virgin lands of

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World»

Look at similar books to Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Boris Yeltsin: The Decade that Shook the World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.