Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

VERA RUBIN

a life

JACQUELINE MITTON

SIMON MITTON

BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2021

Copyright 2021 by Jacqueline Mitton and Simon Mitton

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

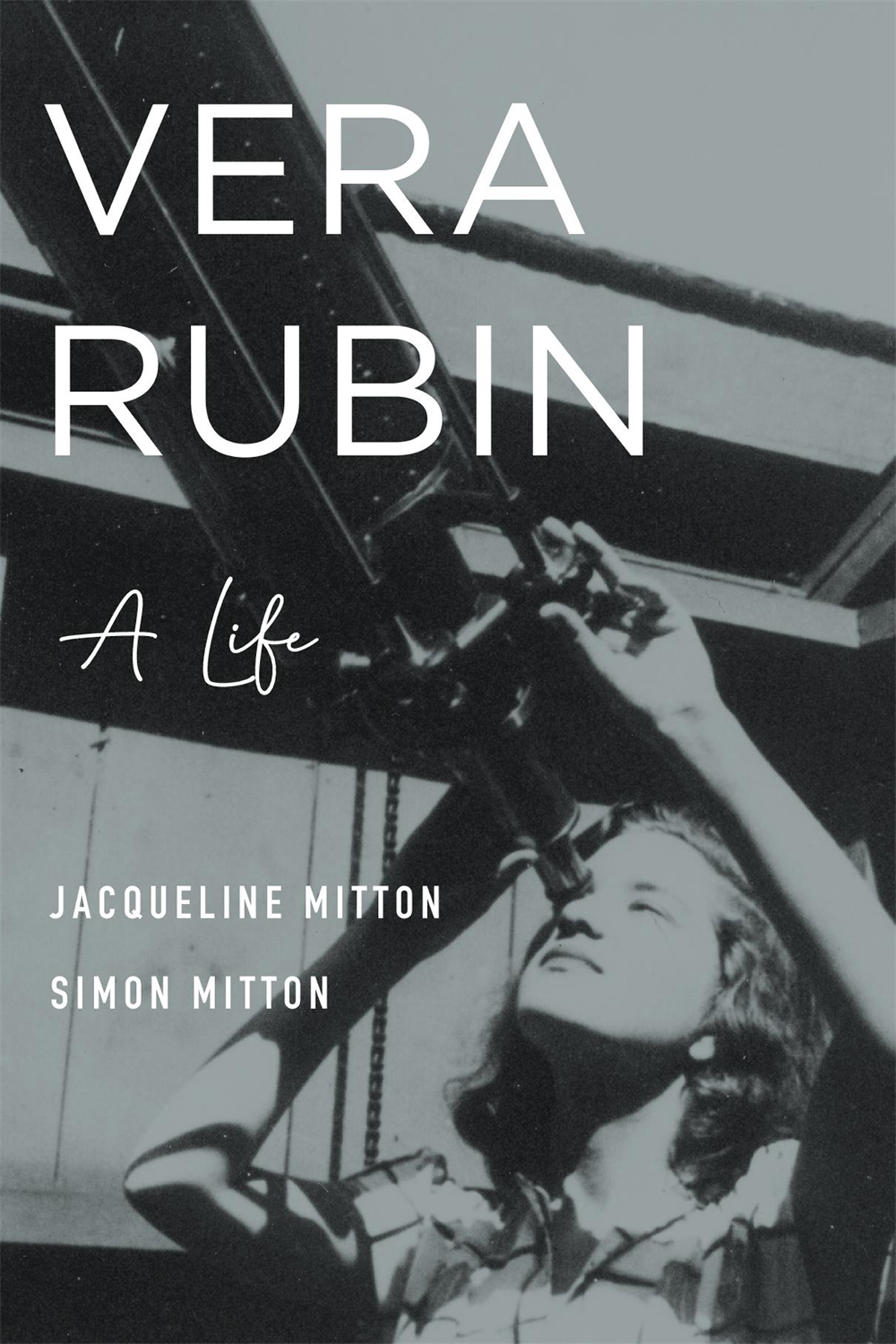

Jacket design: Graciela Galup

Jacket art: Courtesy Carnegie Institution for Science, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Archives. Photograph by A X Photo Studio, Poughkeepsie, NY

978-0-674-91919-8 (cloth)

978-0-674-25936-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25938-6 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Mitton, Jacqueline, author. | Mitton, Simon, 1946author.

Title: Vera Rubin : a life / Jacqueline Mitton and Simon Mitton.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020032833

Subjects: LCSH: Rubin, Vera C., 19282016. | AstronomersUnited StatesBiography. | Women astronomersUnited StatesBiography. | Dark matter (Astronomy)

Classification: LCC QB34.5 .M58 2021 | DDC 520.92 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032833

This book is dedicated to Vera Rubins family:

her sons, David, Karl, and Allan

her sister, Ruth

her grandchildren and great-grandchildren

and also to the memory of

Bob Rubin (19262008)

and

Judy Young (19522014)

Contents

Vera Rubin achieved many firsts, the latest being that she is the first woman to have a major observatory named after herand also after in the other sense of posthumously. Three and a half years after she died, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope project, being built in Chile, has been renamed The Vera C. Rubin Observatory. It is a huge telescope and will break new ground, as Vera Rubin did in her lifetime.

She had a long and highly productive life, mostly based in Washington, DC, at the Carnegie Institution for Sciences Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, retiring finally at age eighty-four. For me, she was a trailblazer in two ways: detecting the presence of dark matter through the way galaxies rotate; and arguing for the recognition and inclusion of women in astronomy.

Dark matter, although invisible, is as it turns out a major component of the universe. We were unaware of its existence until we were forced by Vera, and then also some radio astronomers, to accept that something invisible was affecting the way galaxies rotate, especially in their outer regions. The implications were so dramatic that she had trouble, initially, in getting her observational data accepted. The existence of dark matter was forced upon her (and all of us) by her careful observations of the motion of stars in carefully selected galaxies. Her observational work on the rotation of galaxies has been held in high esteem, and her data is still regarded as outstanding.

As well as being a biography, this book gives an authoritative account of the development of astrophysics over the last seventy years, and in particular the development of extragalactic astronomy. There is useful historical context, with the authors describing significant (with hindsight) papers that had little impact when first published. Thumbnail sketches of other important astronomers she met or worked with add texture to the story.

My strongest memory of Vera will be of her kindness, and her genuine interest in what one was doing professionally. My next memory of her is her tenacity. She did not have it easy, largely because she was a woman and a wife and mother. She was forever juggling commitments while clinging (sometimes precariously) to her chosen profession, observational astronomy. And the third memory is what she did to advance the position of women in science.

She was modest, kindly, determined (when she needed to be), generous and encouraging, astute, thoughtful, and persuasive. All this is brought out wonderfully in this biography. At the start of her career, Martin Schwarzschild showed her, in her own words, humanity and gentleness, and she would do this herself, especially to other female astronomers.

Given that she was of the generation that she was, and that she had four children, it is remarkable that she had any career at all. Her desire to stay intellectually active while rearing children resonates. Much credit must go to her husband, Bob. How fortunate that he worked in an area (scientific research) where he had some flexibility and was able (as well as willing) to be supportive in deed as well as in word. He was a pioneer as much as she was.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell

Oxford, June 2020

On January 6, 2020, the 235th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Honolulu received the official announcement that the Vera C. Rubin Observatory Designation Act had become Public Law number 11697 in the United States. Never before had a national astronomical observatory been named to honor a woman. So why did Vera Rubin merit this notable distinction?

In December 1950, a young and inexperienced Vera Rubin had attended her first AAS meeting, in Haverford, Pennsylvania, to present some controversial conclusions from her masters thesis. Most of her audience on that occasion were highly critical of the work of the unknown twenty-two-year-old, who had not even started to study for a doctorate. Sixty-nine years later, however, at this 2020 meeting, Rubin is universally acknowledged as one of the most influential female astronomers of her generation, whose life is worthy of commemoration with an unprecedented accolade. After her death at the age of eighty-eight, on December 25, 2016, the Division on Dynamical Astronomy (DDA) of the AAS lost no time in naming its recently created Early Career Prize to honor Vera Rubin, a remarkable individual who contributed to a transformation in astrophysics and championed the status of women in science. The DDA described its decision as particularly fitting since she was not only an extraordinary scientist, but also well known for her kindness towards and encouragement of young scientists.

The official redesignation of what was formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) project, confirmed into law by the president of the United States on December 20, 2019, was an even more impressive tribute.

Rubin is remembered first and foremost for her pioneering, long-term studies of spiral galaxies. Her stunning and unexpected discoveries helped to convince astronomers that dark matter is a real entity and, further, that it exists in vast quantities. Rubin never claimed that she had discovered dark matter as a concept, although others have mistakenly attributed discovery to her. Cosmologist Fritz Zwicky, writing in 1933, is credited as the first person to suggest there could be such a thing, because known astrophysics could provide no explanation for his observations of how galaxies are moving within their clusters. However, few people paid attention to Zwicky at the time, and the idea lay more or less fallow for almost forty years. From the mid nineteen-sixties, Rubin and her colleague Kent Ford decided to investigate a different kind of motion: how the stars and gas clouds belonging to an individual galaxy revolve around the galaxys center. They had no intention of searching for dark matter but, to her surprise, Rubin found compelling evidence that galaxies are immersed in vast halos of it. In fact, it emerged that some ten times more of this mysterious invisible stuff exists than all the particles of ordinary matter in stars and gas clouds put together. Rubin was a meticulous observer and processed her data with the utmost attention to detail, so eventually the truth dawned. Even the most skeptical of critics could not deny the credibility of the observational results she and Ford published, and what these facts implied, especially in the face of developments in theoretical astrophysics and radio astronomy happening at about the same time.