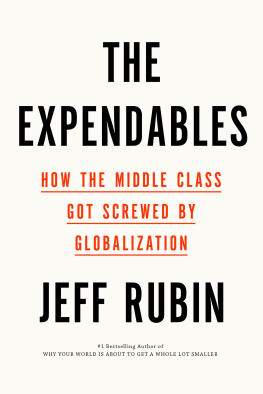

VINTAGE CANADA EDITION, 2013

Copyright 2012 Jeff Rubin

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Published in Canada by Vintage Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, in 2013. Originally published in hardcover in Canada by Random House Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, in 2012. Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited.

Vintage Canada with colophon is a registered trademark.

www.randomhouse.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Rubin, Jeff

The end of growth / Jeff Rubin.

eISBN: 978-0-307-36091-5

1. Economic development. 2. International economic relations. 3. Petroleum industry and tradeEconomic aspects. 4. Economic forecasting. I. Title.

HD75.R82 2013 338.90090512 C2011-908175-X

Image credits: Valdis Torms/Shutterstock.com

Maps: Paul Dotey

v3.1

IN MEMORY OF MY PARENTS,

SHIRLEY ROSE RUBIN AND DR. LEON JULIUS RUBIN

[ CONTENTS ]

[ INTRODUCTION ]

THE LAST MAJOR BARE-KNUCKLE prizefight in America happened in 1889. Shortly after midnight on July 8, John L. Sullivan knocked out Jake Kilrain in the seventy-fifth round, and with that an era was over.

And rightly so. Illegal in thirty-eight states at the time, bare-knuckle matches were barbaric. Gloves became mandatory when boxing adopted the Marquess of Queensberry rules, a civilized turn that set the stage for the advent of great heavyweights like Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis. Although gloves helped usher in boxings golden age, tossing out the London Prize Ring Rules that had governed bare-knuckle matches came at a cost. In the bare-knuckle days, fighters were so worried about breaking a hand that most of their punches were body shots. Todays fight crowds may love seeing heavyweights land knock-out punches to the head, but whats less thrilling is the number of brain-related injuries suffered by boxers. Repeated blows to the head can lead to something doctors call Dementia Pugilistica, a condition every bit as bad as it sounds.

Even changes made with the best intentions can have unintended consequences. More than a century ago, the powers that be intervened to do what they thought was best. They never dreamed that gloves could create any problems beyond putting a few bare-knuckle fighters out of work. And today, the folks pulling the levers of the global economy are making choices that are already costing us much more than you might think. When it comes to setting economic policy, trying to cushion the blow can sometimes be a whole lot worse than taking a few punches with the gloves off.

The economic recovery since the world officially crawled out of the last recession in 2009 has been wobbly at best. If you read the business section or listen to financial market pundits, youll know that majority opinion suggests the roots of the financial crisis of 20089 lay in the debt-ridden wreckage of the United States housing market. The prescription resulting from that diagnosis involved taxpayers around the world opening up their wallets to bail out insolvent banks. The sums of money required were enormous, but we were told the ramifications of doing nothing would be even greater. Finance ministers and central bankers warned that government intervention was desperately required to save the global financial system from collapse and spare us from an economic fate worse than the Great Depression.

And so taxpayers underwrote the biggest bailout in the history of the financial industry.

If flaws in the global financial system were serious enough to jeopardize our economic future, then common sense dictates that deep reforms would unfold once the crisis passed. Since banks barely escaped insolvency as a result of carrying too much debt and exposure to poorly understood financial derivatives, it was fair to assume that regulators would soon put global banks on a much tighter leash. After shelling out trillions to prop them up, taxpayers reasonably expected to see new safeguards put in place to keep us from tumbling into the same mess ever again.

Well, guess again, because little has changed.

The global financial system is still as interconnected and full of risk as ever. A few familiar players are missing, such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, but the cast of characters is otherwise intact. And once again were hearing ominous sounds from the financial markets. Only this time around, instead of the United States housing sector being shaky, the deepest rumblings are emanating from across the Atlantic.

Europe is in the grip of a financial crisis. Greece is close to defaulting on its debt, and Portugal, Italy, Ireland and Spain arent in much better shape. The European Central Bank is writing checks to keep these governments afloat and hold the eurozone together. Meanwhile, German taxpayers, who are footing much of the bill to keep their neighbors solvent, are wondering what theyre getting for their money and if theyll ever see any of it again.

In the world of modern finance, you dont have to live in Europe to be touched by what happens in Athens or Madrid, any more than you needed to own a home in Cleveland to feel the collapse of the subprime mortgage market. Thanks to our integrated global banking system, a financial market accident in one corner of the world now puts everyone at risk. An investment arm of your local bank could be exposed to a French bank, which in turn holds a big position in Greek bonds that are about to go horribly offside. When that happens, the pain ripples from Greeces bond market, to the French bank, to your regional investment dealer, and eventually onto your doorstep. Half a world away, you and millions of other depositors have a direct interest in Greek debt, even though none of you personally have invested a penny in Greece.

In this era of electronic trading, money travels at the speed of light across national borders with little regulation. The global financial system is an interconnected web that links our economic fates together as closely as our Facebook pages. When Greece or Italy cant pay their bills, there are few places to hide. We learned that lesson a few years ago when homeowners in Florida, Nevada and Arizona began missing their monthly mortgage payments.

There certainly wasnt any cover to be found inside the walls of a Canadian investment bank. Why do you think Im an author now?

I spent nearly twenty years as chief economist of CIBC World Markets, a major Canadian investment bank with clients and operations around the world. It was certainly a good way to earn a living. Global investors are constantly grappling with changing financial conditions, which puts the services of a chief economist in high demand. One week youre advising sovereign wealth funds in exotic locales such as Kuwait or Singapore, and the next youre back in North America telling heavyweight pension funds how economic events will impact stocks, bonds and currencies. On other days, youre visiting global financial capitals and eating at nice restaurants with powerful portfolio managers and high-ranking government officials.

The press frequently chases you for comments, which opens up an entirely different aspect of the job. A chief economist is a de facto spokesperson for a banks position, whether or not thats something either party really wants. Ultimately, it was that part of the job that forced me to rethink my two-decade-long career.