All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

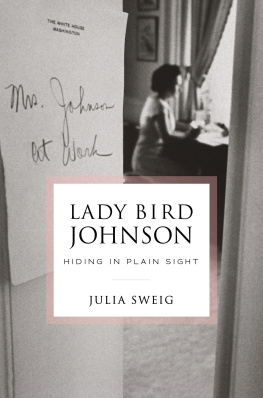

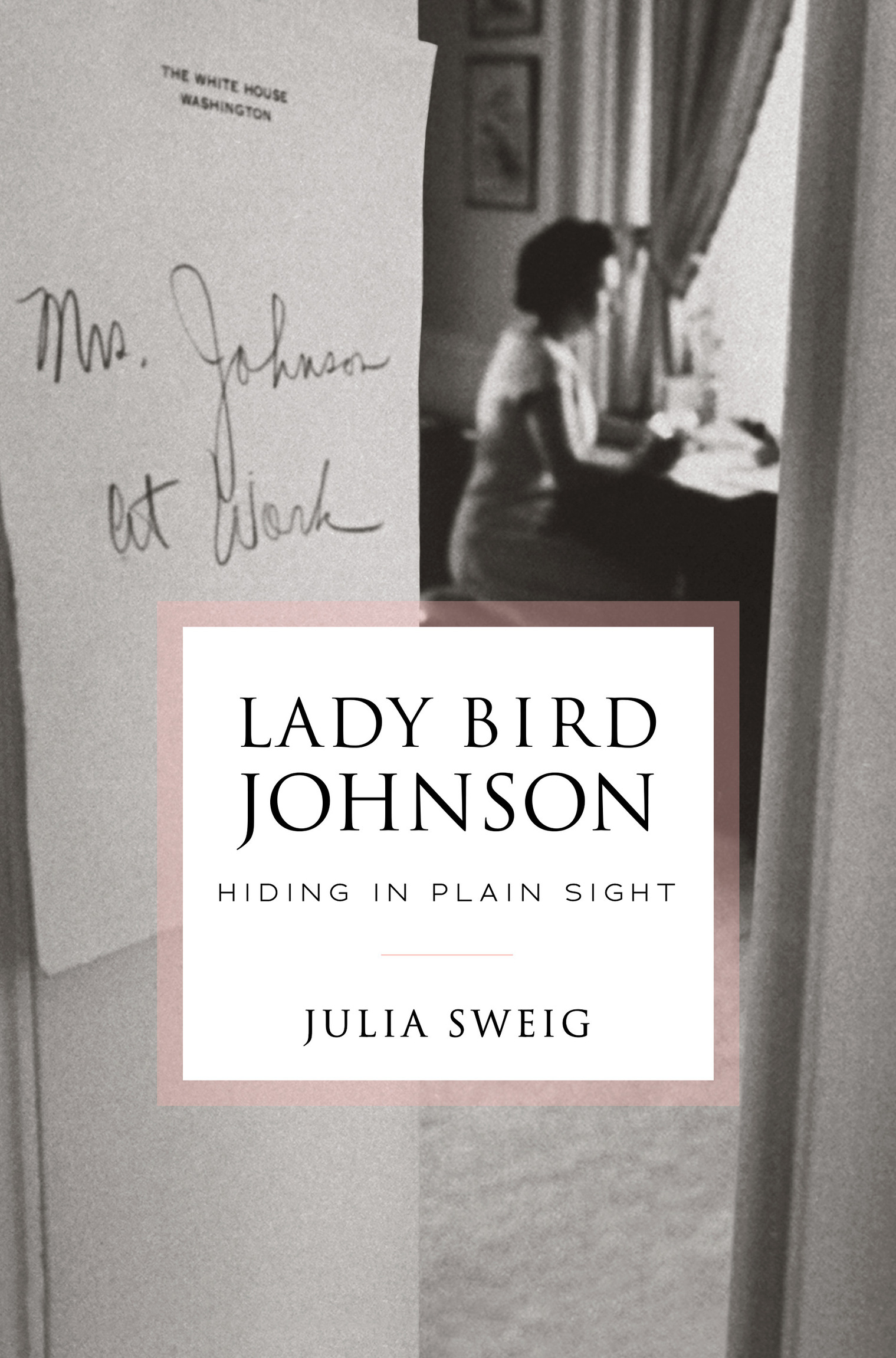

Names: Sweig, Julia, author.

Title: Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in plain sight / Julia Sweig.

Description: First edition. | New York: Random House, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001666 (print) | LCCN 2020001667 (ebook) | ISBN 9780812995909 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812995916 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Johnson, Lady Bird, 19122007. | Presidents spousesUnited StatesBiography. | Johnson, Lyndon B. (Lyndon Baines), 19081973. | PresidentsUnited StatesElection1964. | United StatesPolitics and government19631969.

Classification: LCC E848.J64 S94 2020 (print) | LCC E848.J64 (ebook) | DDC 973.923092 [B]dc23

Lady Bird Johnsons White House Diary

Eight days after the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and a week before she moved into the White House, Lady Bird Johnson taped the first of over 850 diary entries narrated during her White House years. The first recording describes in vivid detail her experience of November 22, 1963, that fateful and dreadful day in Dallas. Her final entry, dated January 31, 1969, recorded from the LBJ Ranch, recounts the prosaic terms of her adjustment to private life. In 1970, Holt Rinehart published the nearly eight-hundred-page A White House Diary to mixed reviews. The redacted selection of her diary represented just a fraction of the 1,750,000 words she recorded during the 1,886 days of Lyndon Baines Johnsons presidency.

Six years after her death in 2007, the LBJ Presidential Library began the public release of the diary recordings and transcripts, in almost entirely unredacted form. Listening to and reading the contemporaneous accounts of her White House years, one finds in Lady Bird Johnson a prodigiously disciplined participant, actor, and witness to and student of history. Hidden within the sheer scale and, at times, overwhelming detail of the diary are golden nuggets of insight about her husband and herself, the marriage they created, and the ambitions animating the presidency they together crafted. Similarly rewarding and surprising are the elegant word pictures from her nature writing, her character studies of the men and women who entered and exited their world, and the riveting details of her experiences during the White House years. Like the correspondence between Abigail and John Adams, her diary is indispensable for understanding Lady Bird and Lyndon Johnson, and yet the diarys daunting scope, combined with the massive documentation from her husbands life and presidency, seems to have relegated Lady Bird and her diary if not to oblivion, then to the role of a diminished supporting actor in the sweeping narrative dominated by her husband.

Perhaps this was by design. In college, she studied journalism and history, and throughout her career as a political wife, those two skills served her well as she crafted the public record of what she called our presidency, Lyndon Johnsons legacy and her own. She was in full command of her sources, drawing from her and her husbands daily diaries, newspaper clippings, and the voluminous documents compiled each day by her staff. Hers is a perspective not merely of a dutiful political spouse but of a fully engaged participant in many of the deepest workings of the presidency.

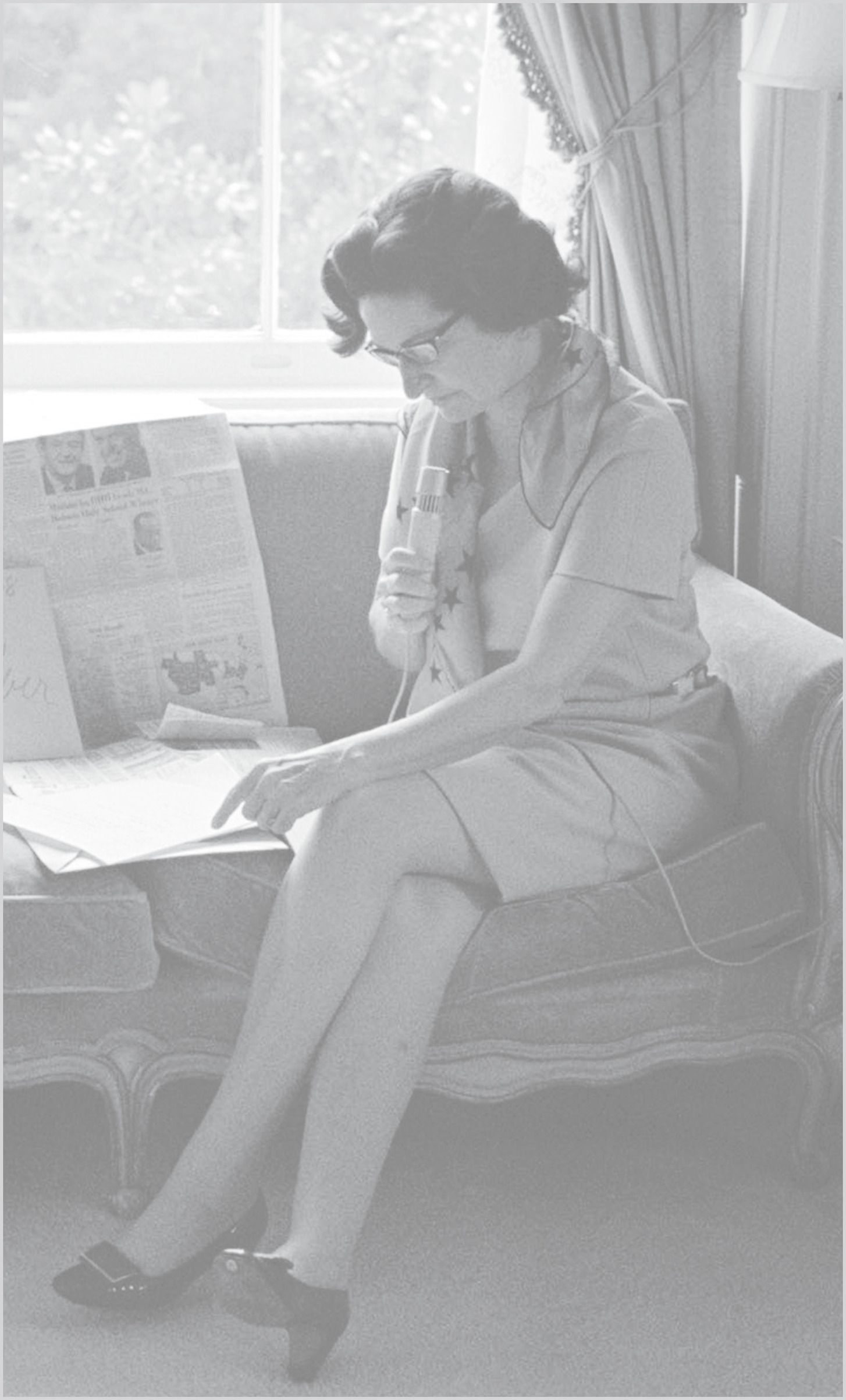

When Mrs. Johnson recorded the first entry in the ten days following the assassination, before she moved into the White House, she did this primarily as a form of therapyto help me over the shock and horror of the experience of President Kennedys assassination, as she wrote the Warren Commission, not intending at the time she recorded it that the tape be used. But she decided that it reflected her best, most accurate recollection of the day, and thus submitted the seven-page transcript of the recording as her formal testimony in July 1964. Whether on her light-blue velvet couch in her private sitting room looking out over the magnolia tree Andrew Jackson had planted in his wife Rachels memory, to the Washington Monument in the distance, or at her desk looking into the Rose Garden and Lyndons office, in hotels or at the Ranch, she recorded hundreds of entries in her diary, a practice she maintained beginning with the first entry, just a few days after November 22, 1963.

* * *

It didnt take long for the exercise to become much more than a form of therapy. In the introduction to the 1970 edition of her diary, she asked and answered the question Why did I record it?

I think for the following reasons: I realized shortly after November 22, thatamazed and timorouslyI stood in a unique position, as wife of the President of the United States. Nobody else would live through the next months in quite the way I would and see the events unroll from this vantage point. And this certain portion of time I wanted to preserve as it happened. I wanted to remember it, and I wanted my children and grandchildren to see it through my eyes. The second reason is a difficult one to describeit has something to do with discipline. I wanted to see if I could keep up this arduous task. In a way, I made myself a dare. And somehow if you make yourself record what went on in the day, it makes you more organized, it makes you remember things better. My third reason for recording this diary was that I like writingfearful labor though I sometimes find itI like words. As time passed[,] there began to emerge a fourth reason, dimly felt, something like thisI wanted to share life in this house, in these times. It was too great a thing to have alone.

In his review of the edited collection, the New York Times book critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt described the huge pile of motionless material as personal but curiously unrevealing. The diary can at times be anodyne, and yes, eye-glazing in its detail about whom Lady Bird seated where at which state dinner and the like. This is where the dutiful scribe seems to appreciate a reality that may be opaque for most readers: the way that seating arrangements at White House state dinners represent the ultimate exercise of power and prerogative. Lady Bird was adept at advancing both, even if her account can at times appear reticent. However motionless one reviewer may have found the diary, he surmised nevertheless that Lady Bird Johnson was shrewd, able, and extremely likeable. How, then, is it possible for several thousand hours of recordings to be nevertheless unrevealing? Here, like so many of her and LBJs biographers, Lehmann-Haupt fell for Lady Birds very female gift, and one in dramatic contrast to her husbands tendency to overshare, at revealing her experience without revealing herself.