Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA.

E-mail:

www.shirebooks.co.uk

2016 Susan Cohen.

All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 821. ISBN-13: 978 0 74781 507 5

PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 78442 094 9

ePub ISBN: 978 1 78442 093 2

Susan Cohen has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

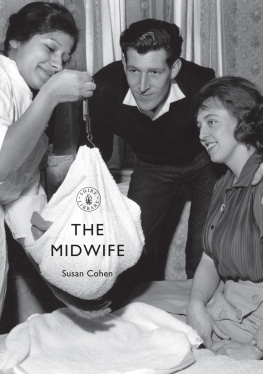

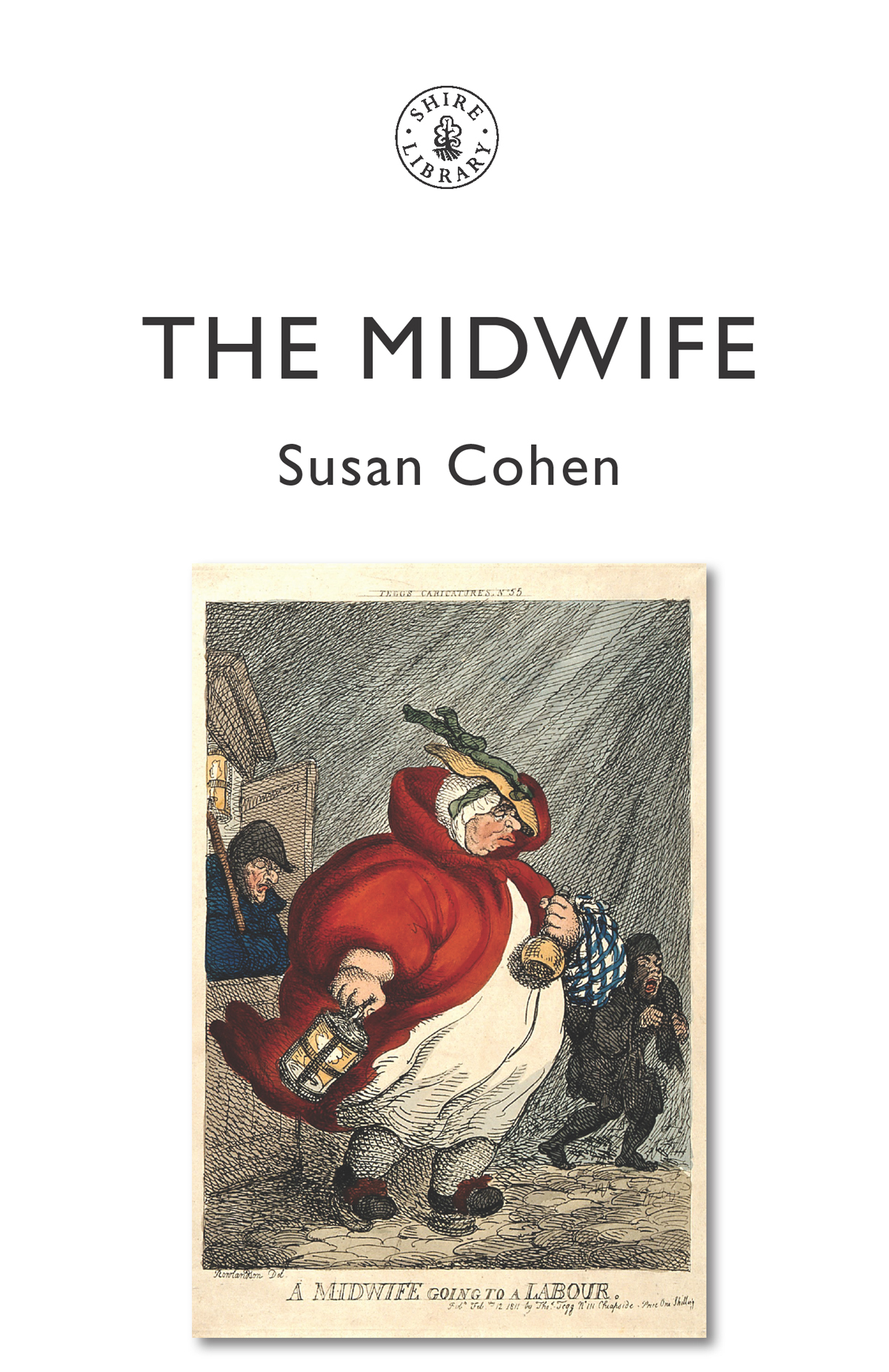

COVER IMAGE

A midwife weighs a baby while visiting a family at home, March 1965. (Topfoto)

TITLE PAGE IMAGE

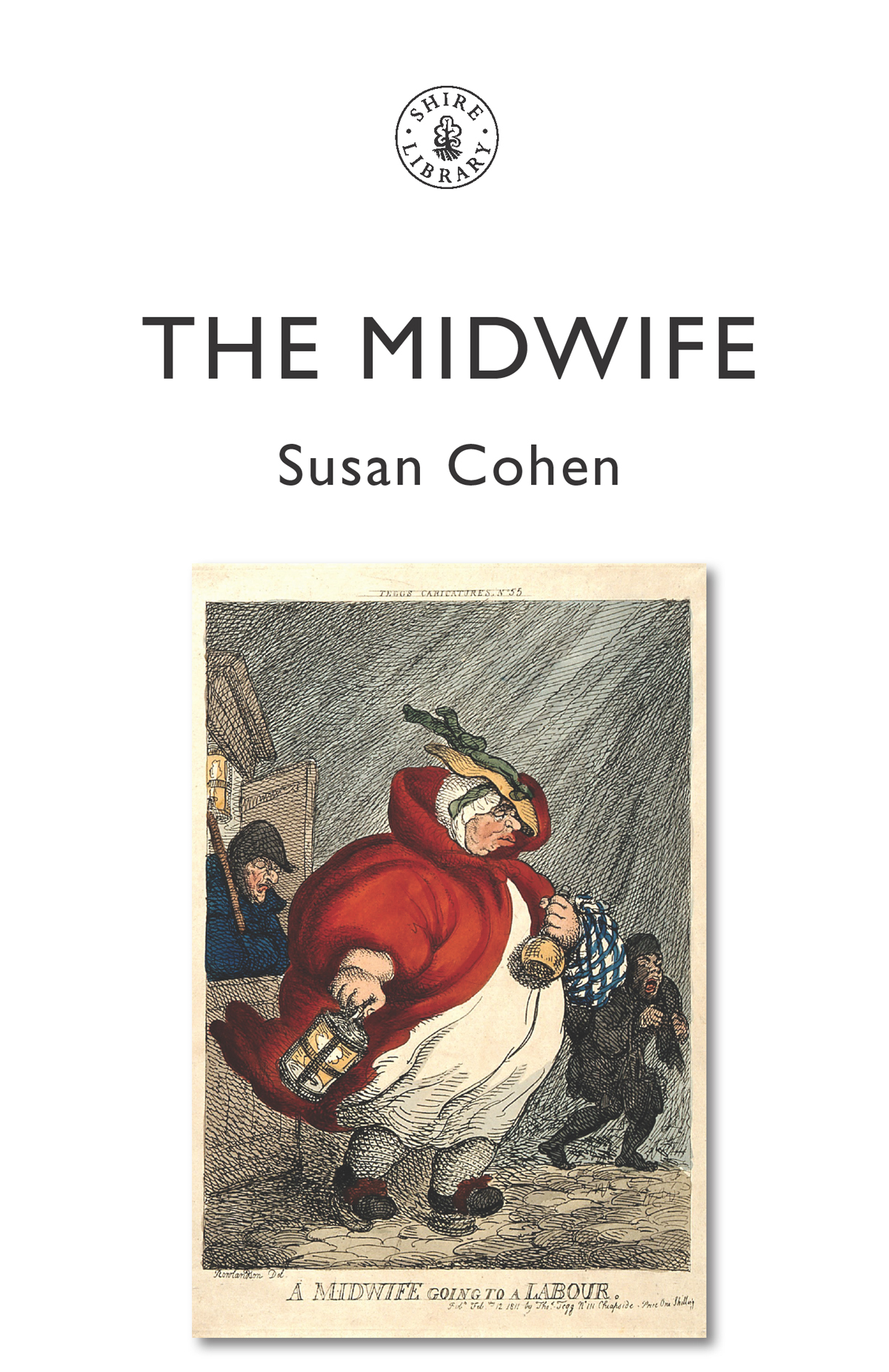

Thomas Rowlandsons caricature, about 1811, represents a stereotypical view of midwives in the early nineteenth century as blowsy, obese, ignorant and prone to drink one verse about midwives described them as Taking snuff, drinking gin and tea, and the midwifes half-crown fee.

CONTENTS PAGE IMAGE

A mother and her newborn baby going home from hospital, c. 1950s.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A special thank you to Penny Hutchins for her invaluable assistance with providing images from the Royal College of Midwives collection at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Also, thanks to Nicky Leap and Billie Hunter for permission to include quotes from The Midwifes Tale, and to Lindsay Reid for allowing me to quote from Scottish Midwives.

Photograph acknowledgements can be in the previous pages.

CONTENTS

A seated woman giving birth aided by a midwife and two other attendants. In the background, two men are looking at the stars and plotting a horoscope. Woodcut, about 1583.

THE EARLY DAYS

The role of the midwife, attending to and assisting women in childbirth, has been recorded since time immemorial, but the traditionally female practice was unregulated, and was not officially recognised as a profession in Britain until the Midwives Act was passed in England and Wales in July 1902. This was undoubtedly a turning point, but was just the beginning of a long process, fraught with difficulties and debate, during which midwifery developed to become the highly skilled branch of nursing, open to men and women, which is recognisable today.

For centuries, practitioners were a motley crew, ranging from the handywoman, epitomised in the nineteenth century by Charles Dickens character, Sairy Gamp, to the careful, knowledgeable and empathetic midwife. Handywomen, who typically acted as midwife, monthly nurse and the layer-out of the dead, were commonly unhygienic, illiterate and frequently dangerous, but were all that was available to poor women. The best and the safest birth attendants, engaged by the more discerning and educated in society, learnt their craft from their mothers or an elder, served lengthy apprenticeships and, in turn, passed their knowledge onto the next generation. Flora Thompsons fictional rural midwife, old Mrs Quinton, in Lark Rise to Candleford, was one such woman, who recognised a rare crisis and the need to call the doctor. She took pride in her work and was valued by the local doctor, who appreciated the important role she played in the community.

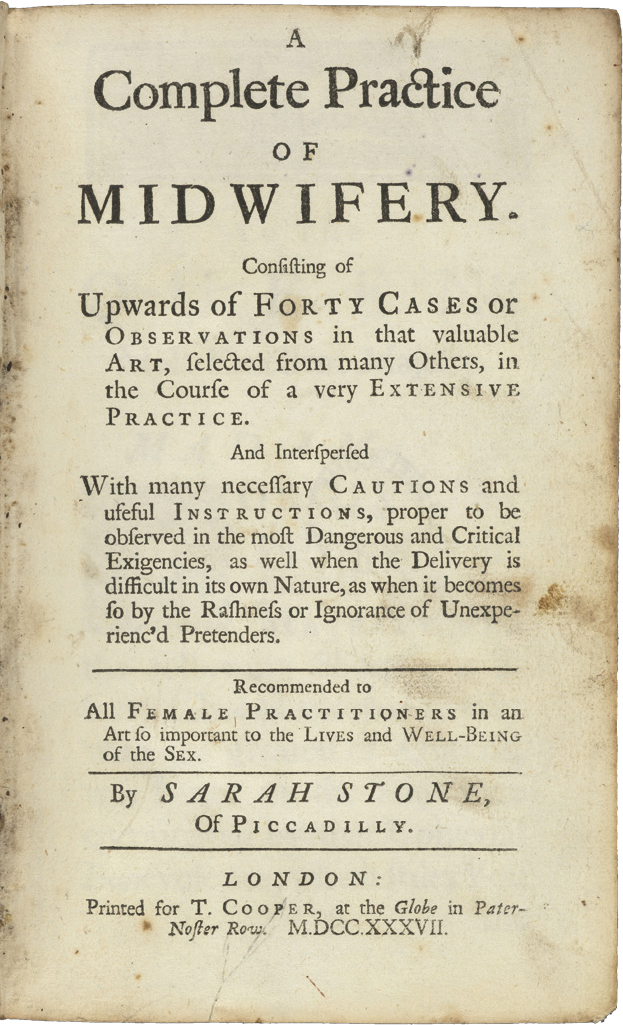

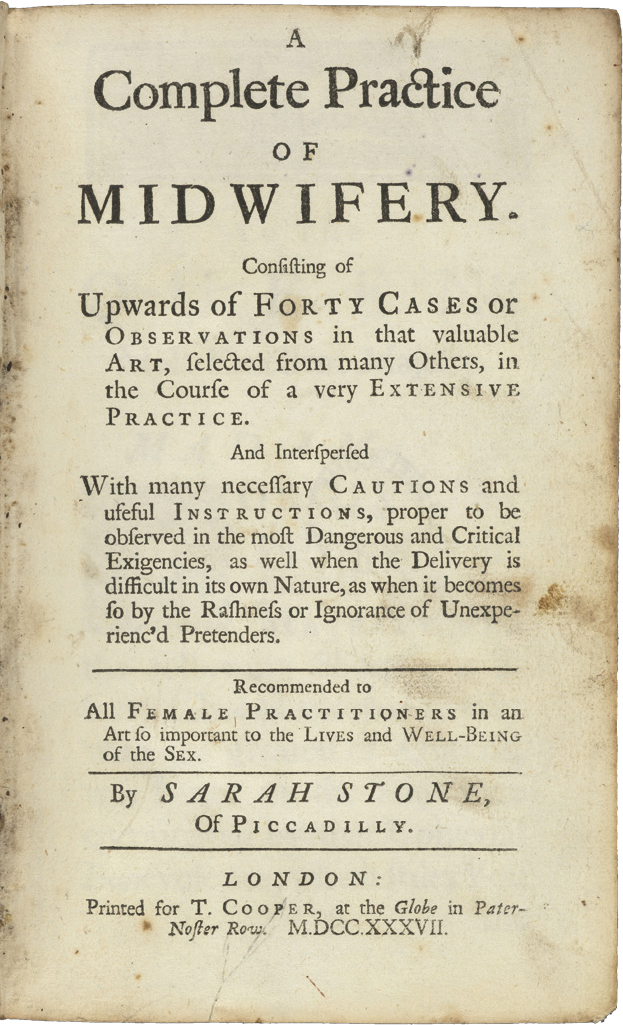

Childbirth was viewed as a natural process, with ordinary married women or widows acting as midwives or handywomen. They helped their neighbours give birth and provided practical help with childcare and domestic tasks; in return they earned a modest livelihood. Most midwives were, like their patients, educationally disadvantaged. Even if they were literate, as women they were denied the opportunity to learn anatomy, attend lectures or read the specialist books traditionally written in Latin and Greek. Mrs Jane Sharp was one of the earliest midwives to put her wealth of experience to practical use by publishing the first English textbook for midwives in 1671: The Midwives Book, which was also aimed at mothers and fathers, and provided advice on conception, pregnancy, the birth itself and postnatal care, along with anatomical illustrations and descriptions of difficult births. Another midwife, Mrs Sarah Stone of Taunton, whose book A Complete Practice of Midwifery followed in 1737, was intended to ignite the confidence of even midwives of the lowest capacity so they could deliver their women, without calling in, or sending for, a Man, in every little seeming difficulty.

This caricature by Isaac Cruikshank, about 1793, depicts the man-midwife as a split figure half male, half female.

Mrs Sarah Stones textbook, A Complete Practice of Midwifery (1737), was intended for all female practitioners in an art so important to the lives and wellbeing of the sex.

The man-midwife was not new, but was gaining a foothold in upper-class circles from the 1700s, on the basis that he had superior knowledge. This received wisdom was clearly not always the case for, as Mrs Stone pointed out, some had very dubious qualifications, including the pork butcher who gave up stuffing sausages to deliver babies, mainly because it was a lucrative business.

These men frequently applied the recently introduced obstetric forceps, which most midwives would not use for fear of the damage and danger they caused mothers and babies. Mrs Stone found the instruments of very little use, and reported using them only four times in her life, then declared I am certain, where twenty women are delivered with instruments (which is now become a common practice) that nineteen of them might be delivered without, if not the twentieth.

Forceps, about 174060. Forceps were first described by Edmund Chapman (died 1738) in his Treatise on the Improvement of Midwifery (1733). The steel blades of William Smellies forceps were covered with leather, and were greased with hogs lard before insertion.

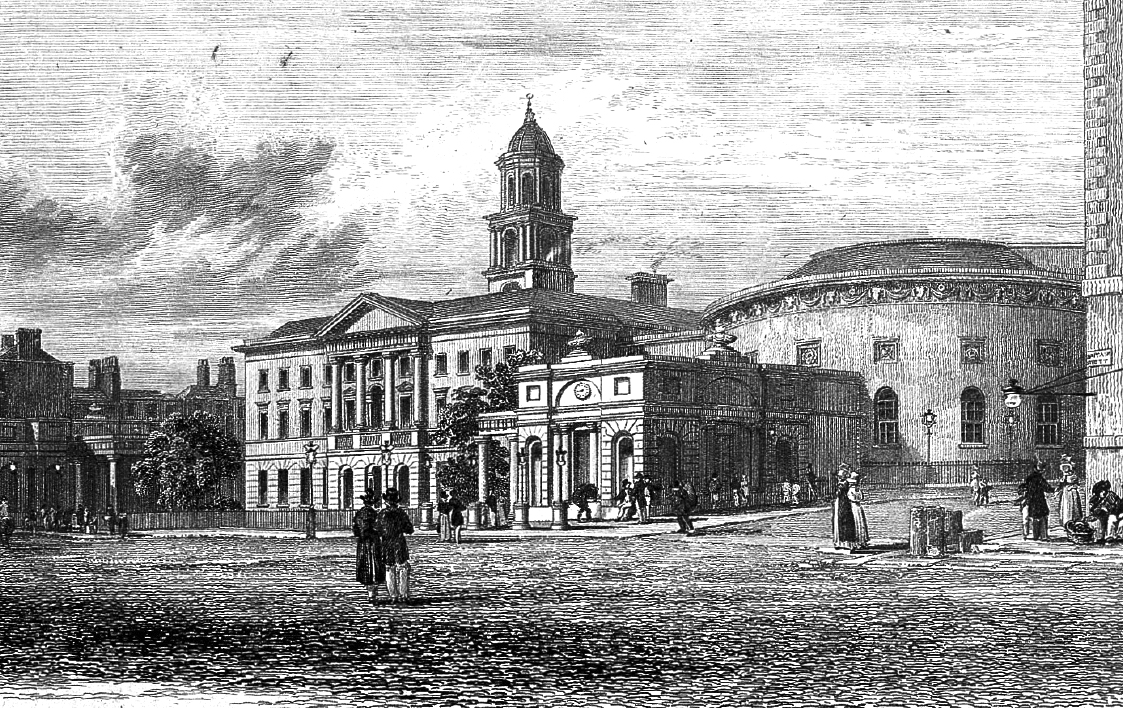

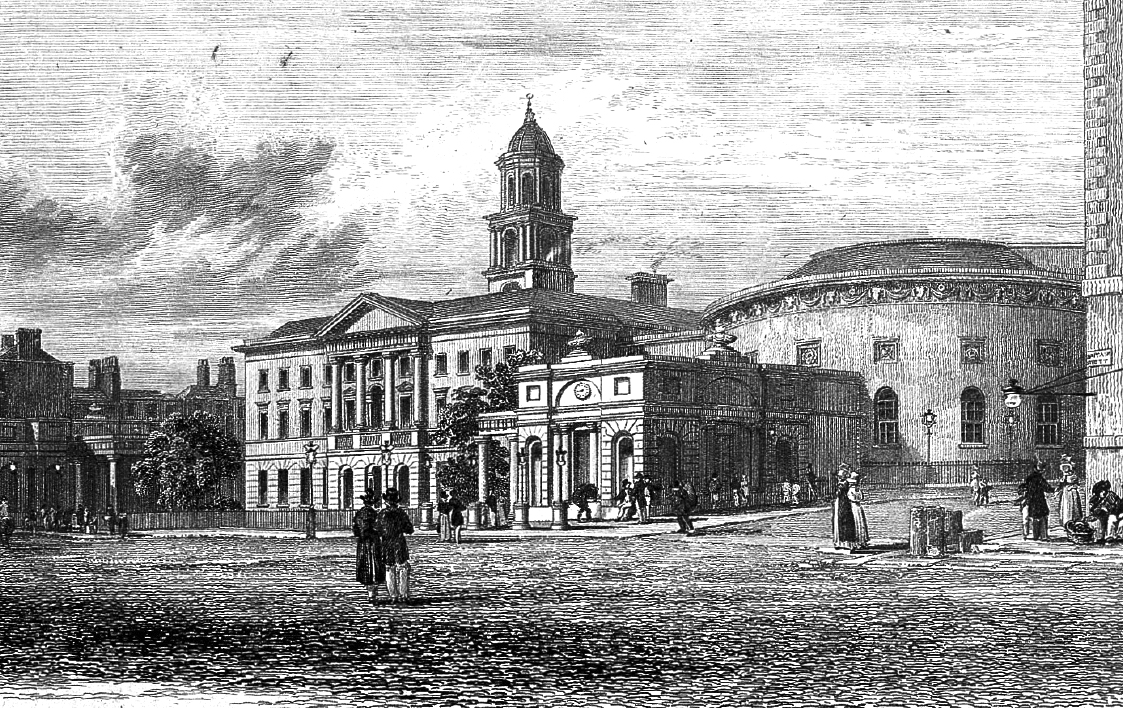

An etching of the Rotunda and Lying-In Hospital, Dublin, Ireland, 1821. Dr Bartholomew Mosse, surgeon and man-midwife, founded the original Dublin Lying-in Hospital in 1745 as a maternity training hospital, the first of its kind. His aim was for every county in Ireland to have a trained midwife.

The encroachment of man-midwives had financial implications, even in a relatively small town such as Sheffield. In 1787 there were thirteen surgeon/man-midwives advertising their services, leaving the local midwives with only the very poorest patients to attend. The establishment of more midwifery training courses for men, especially in London, only exacerbated the situation. Amongst the most prestigious were those run by William Smellie, whose book,