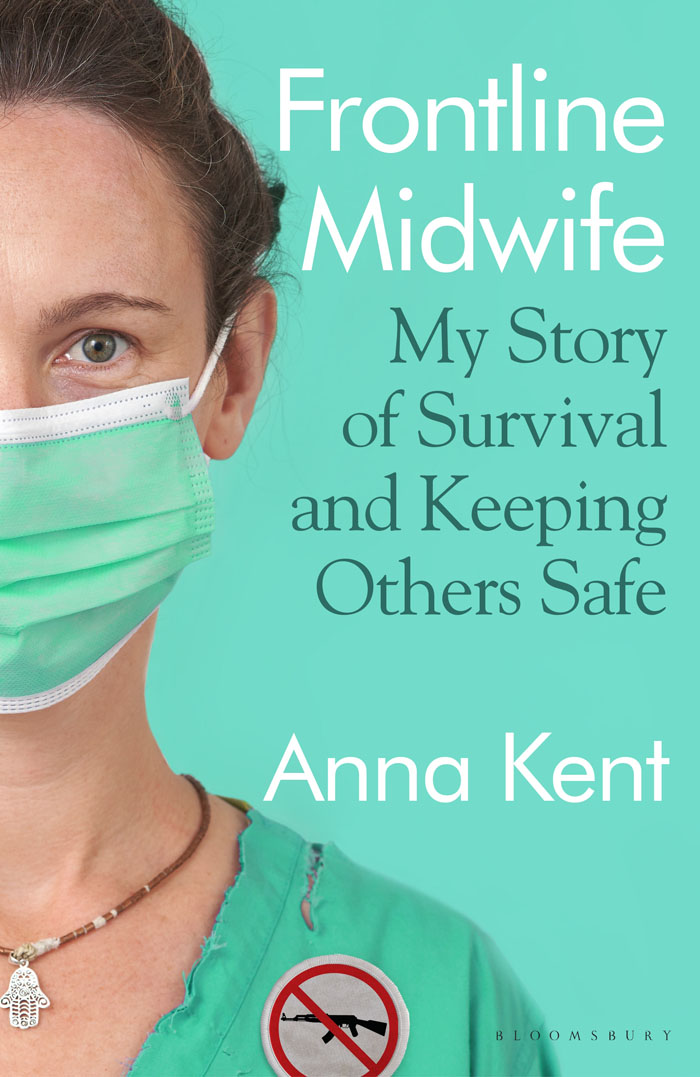

Frontline Midwife

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2022

This electronic edition first published in 2022

Copyright Anna Kent and Julia Gregson, 2022

Anna Kent and Julia Gregson have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work.

Some names and details of individuals have been changed to preserve their anonymity

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-5266-2551-9; TPB: 978-1-5266-2552-6; EBOOK: 978-1-5266-2549-6; EPDF: 978-1-5266-5244-7

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

For Aisha

This publication and its content has not been authorised, approved or endorsed by Mdecins Sans Frontires. The views expressed in this publication are Anna Kents own and do not reflect the views of Mdecins Sans Frontires.

Contents

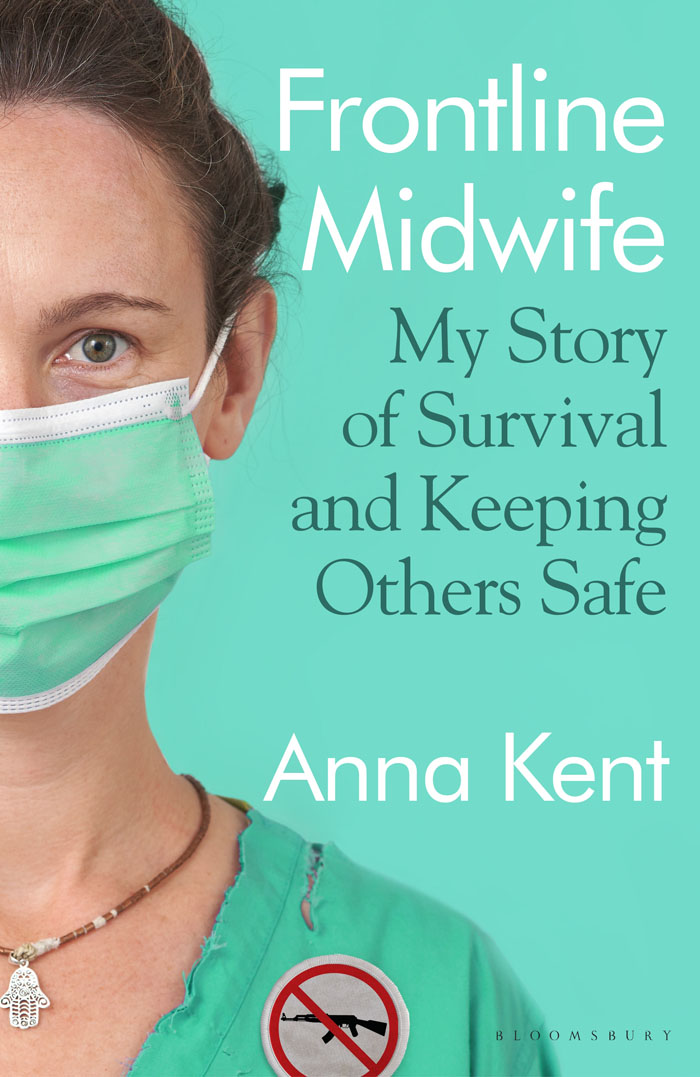

When I talk about aid work, most listeners expect a feel-good, inspiring story, where good inevitably wins over evil. This was the narrative I naively imagined as a twenty-something-year-old, heading out on my first intrepid adventure. And sometimes wonderful things do happen. But the reality of humanitarian crises is that they are always complicated, often harrowing, and there is certainly no simple fix.

I fervently hope that by speaking out on behalf of the women Ive been honoured to meet sometimes in the most amazing, and the most horrific, of circumstances that somehow their lives may be improved. Their stories deserve to be told, and to protect them, all patients have been anonymised. Every extraordinary birth described in this book has happened in real life and many of the scenes are graphic.

Trigger warnings are given for: baby loss, gender-based violence, birth-related injuries and maternal death. I have a duty to protect you, rather than harm you with my words. But equally, I want you to share the joy, laughter and heroism of the many extraordinary women and families I have met through my frontline work as a nurse and midwife.

April 2007. I havent met the woman on the plane yet, but our paths will cross in a matter of days, and one day the smell of her will haunt me. Its the smell of the mothers you cant save, and their babies. When we do meet, well both be juddering on the floor of an old cargo plane in South Sudan, where shell be at the extreme point of her suffering. Her intravenous (IV) infusion will be tied by a sad piece of fraying string to a ripped seat. She will be alone abandoned by her family and unable to tell us who she is and the sight of her will change me forever.

Right now, Im standing half dressed sensible knickers, new T-shirt in an airy, high-ceilinged bedroom in Nottingham that smells of furniture polish and candles. Im staring at a mound of stuff piled on the hoovered carpet, trying to talk to myself in a relaxed, sensible voice.

Do your packing. Calm down, this is what youve been waiting for.

In a few hours time, Ill start the long journey to South Sudan and my first assignment as a nurse with Mdecins Sans Frontires (MSF) Doctors without Borders a medical organisation that sends doctors, nurses and other professionals to conflict zones, natural disasters and epidemics. On one side of the bed sits my backpack, half full already with the essentials: stethoscope, headtorch, multitool, diary and insect repellent. T-shirts, trousers, sarongs and vests sit in a toppling pile next to it. Alhough Ive checked the list endlessly, I know they wont all fit in, but how do you pack everything for nine months into one bag?

Jack, my boyfriend, is still asleep on the other side of the bed, and the sight of his brown hair flopped over his eyes makes me feel like Ive been punched in the stomach. Soon hell drop me off at the airport, well cry and talk of our commitment to each other, before I start the first leg of my journey. Hell come back to this place alone.

Theres been no word of reproach from Jack about me leaving. He supports my decision to be an aid worker with MSF, and even says hes proud of me. Were sure weve talked it through from every angle, and are dedicated to staying together both looking forward to when I return and we can build our lives together. But Im so far from knowing myself, I can only give him a partial explanation of my motives.

My yearning to be an aid worker ignited when I was a child in the 1980s, aghast to see TV news footage of starving children in Ethiopia. Those skinny arms and wide vacant eyes shocked me, as I realised for the first time that such suffering existed in the world. How does this happen? Within my comfortable and loving family home in a small Shropshire village, I hadnt realised inhumane things like starvation could happen, especially to children. I wanted to help. Simple as that, or so I thought. That feeling grew stronger every time the next tsunami or earthquake filled our TV screen with images of suffering people. But now Im twenty-six. I have other darker, complicated reasons for wanting to go, buried inside me like thorns. I cant talk about them yet, even to myself.

Flying MSF workers to remote areas costs a lot, and because the work is tough, and often scary, the dropout rate is high, so MSF tries not to throw you in at the deep end. Its not possible, but they try. For nurses, the minimum requirement is three years experience in acute areas of nursing, either an emergency department (ED), surgery or intensive care, plus some overseas work experience. In my case, I have a masters degree in nursing from the University of Nottingham, and following this, spent three years as an ED nurse at Queens Medical Centre, a massive teaching hospital said to have one of the busiest EDs in Europe, where I coordinated the major trauma unit. This, incidentally, was where I saw my first birth a young, scared, fifteen-year old, whod concealed her pregnancy and told us her abdominal pain was from a fall. She surprised us all by bearing down in a side room, before wed had a chance to fully triage her, shouting fearfully, Dont call me dad, hell kill me!

The babys head was crowning before shed even pulled her jeans past her knees, and this chaotic and disturbing arrival into the world showed me how much I still had to learn. I wasnt a midwife, so while they were wheeling her off, at speed, to the maternity department, baby already in her arms, I decided to do some voluntary shifts in the maternity unit on my annual leave before joining MSF.

Next, I did a diploma in tropical nursing from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, then a short voluntary stint at a rural Zambian hospital, and finally an MSF pre-departure preparation course in Germany.

Im trained and ready for this , I try to reassure myself as I zip up the stuffed backpack, taking comfort that my UK colleagues often describe me as cheerful, or calm in a crisis. Im hoping like hell I can stay this person with MSF. Itll be an adventure too , I silently muse, wondering if Ill want to get an MSF logo tattoo on my return home, as Ive seen successful Olympians do.

Next page