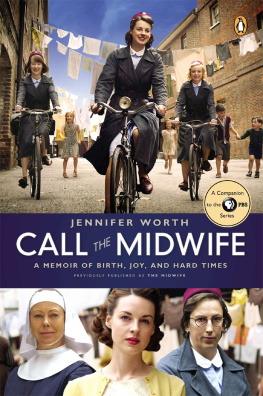

Jennifer Worth

Call The Midwife

This is a work of non-fiction, and the events it recounts are true. However, certain names and identifying characteristics of some of the people who appear in its pages have been changed. The views expressed in this book are the authors.

The history of Mary is also dedicated to the memory of Father Joseph Williamson and Daphne Jones

All nurses and midwives, many long since dead, with whom I worked half a century ago Terri Coates, who fired my memories Canon Tony Williamson, President of The Wellclose Trust Elizabeth Fairbairn for her encouragement Pat Schooling, who had courage to go for original publication Naomi Stevens, for all her help with the Cockney dialect

Suzannah Hart, Jenny Whitefield, Dolores Cook, Peggy Sayer, Betty Howney, Rita Perry

All who typed, read and advised

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

The Curator, Island History Trust, E14

The Archivist, The Museum in Dockland, E14

The Librarian, Simmons Aerofilms

In January 1998 the Midwives Journal published an article by Terri Coates entitled Impressions of the Midwife in Literature. After careful research, Terri was forced to conclude that midwives are virtually non-existent in literature.

Why, in heavens name? Fictional doctors strut across the pages of books in droves, scattering pearls of wisdom as they pass. Nurses, good and bad, are by no means absent. But midwives? Whoever heard of a midwife as a literary heroine?

Yet midwifery is in itself the very stuff of drama and melodrama. Every child is conceived either in love or lust, is born in pain and suffering followed by joy or tragedy and anguish. A midwife attends every birth; she is in the thick of it, she sees it all. Why, then, does she remain a shadowy figure, hidden behind the delivery room door?

Terri Coates ended her article with the words: Maybe there is a midwife somewhere who can do for midwifery what James Herriot did for veterinary practice.

I read those words and took up the challenge.

Jennifer Worth

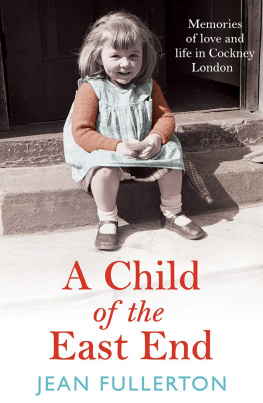

Nonnatus House was situated in the heart of the London Docklands. The practice covered Stepney, Limehouse, Millwall, the Isle of Dogs, Cubitt Town, Poplar, Bow, Mile End and Whitechapel. The area was densely populated and most families had lived there for generations, often not moving more than a street or two away from their birthplace. Family life was lived at close quarters and children were brought up by a widely extended family of aunts, grandparents, cousins and older siblings, all living within a few houses, or at the most, streets of each other. Children would run in and out of each others homes all the time and when I lived and worked there, I cannot remember a door ever being locked, except at night.

Children were everywhere, and the streets were their playgrounds. In the 1950s there were no cars in the back streets, because no one had a car, so it was perfectly safe to play there. There was heavy industrial traffic on the main roads, particularly those leading to and from the docks, but the little streets were traffic-free.

The bomb sites were the adventure playgrounds. They were numerous, a terrible reminder of the war and the intense bombing of the Docklands only ten years before. Great chunks had been cut out of the terraces, each encompassing perhaps two or three streets. The area would be roughly boarded off, partly hiding a wasteland of rubble with bits of building half standing, half fallen. Perhaps a notice stating DANGER - KEEP OUT would be nailed up somewhere, but this was like a red rag to a bull to any lively lad over the age of about six or seven, and every bomb site had secret entries where the boarding was carefully removed, allowing a small body to squeeze through. Officially no one was allowed in, but everyone, including the police, seemed to turn a blind eye.

It was undoubtedly a rough area. Knifings were common. Street fights were common. Pub fights and brawls were an everyday event. In the small, overcrowded houses, domestic violence was expected. But I never heard of gratuitous violence children or towards the elderly; there was a certain respect for the weak. This was the time of the Kray brothers, gang warfare, vendettas, organised crime and intense rivalry. The police were everywhere, and never walked the beat alone. Yet I never heard of an old lady being knocked down and having her pension stolen, or of a child being abducted and murdered.

The vast majority of the men living in the area worked in the docks.

Employment was high, but wages were low and the hours were long. The men holding the skilled jobs had relatively high pay and regular hours, and their jobs were fiercely guarded. Their skills were usually kept in the family, passed from father to sons or nephews. But for the casual labourers, life must have been hell. There would be no work when there were no boats to unload, and the men would hang around the gates all day, smoking and quarrelling. But when there was a boat to unload, it would mean fourteen, perhaps eighteen hours of relentless manual labour. They would start at five in the morning and end around ten at night. No wonder they fell into the pubs and drank themselves silly at the end of it. Boys started in the docks at the age of fifteen, and they were expected to work as hard as any man. All the men had to be union members and the unions strove to ensure fair rates of pay and fair hours, but they were bedevilled by the closed shop system, which seemed to cause as much trouble and ill feeling between workers as the benefits it accrued. However, without the unions, there is no doubt that the exploitation of workers would have been as bad in 1950 as it had been in 1850.

Early marriage was the norm. There was a high sense of sexual morality, even prudery, amongst the respectable people of the East End. Unmarried partners were virtually unknown, and no girl would ever live with her boyfriend. If she attempted to, there would be hell to pay from her family. What went on in the bomb sites, or behind the dustbin sheds, was not spoken of. If a young girl did become pregnant, the pressure on the young man to marry her was so great that few resisted. Families were large, often very large, and divorce was rare. Intense and violent family rows were common, but husband and wife usually stuck together.

Few women went out to work. The young girls did, of course, but as soon as a young woman settled down it would have been frowned upon. Once the babies started coming, it was impossible: an endless life of child-rearing, cleaning, washing, shopping and cooking would be her lot. I often wondered how these women managed, with a family of up to thirteen or fourteen children in a small house, containing only two or three bedrooms. Some families of that size lived in the tenements, which often consisted of only two rooms and a tiny kitchen.

Contraception, if practised at all, was unreliable. It was left to the women, who had endless discussions about safe periods, slippery elm, gin and ginger, hot water douches and so on, but few attended any birth control clinic and, from what I heard, most men, absolutely refused to wear a sheath.

Washing, drying and ironing took up the biggest part of a womans working day. Washing machines were virtually unknown and tumble driers had not been invented. The drying yards were always festooned with clothes, and we midwives often had to pick our way through a forest of flapping linen to get to our patients. Once in the house or flat, there would be more washing to duck and weave through, in the hall, the stairways, the kitchen, the living room and the bedroom. Launderettes were not introduced until the 1960s, so all washing had to be done by hand at home.