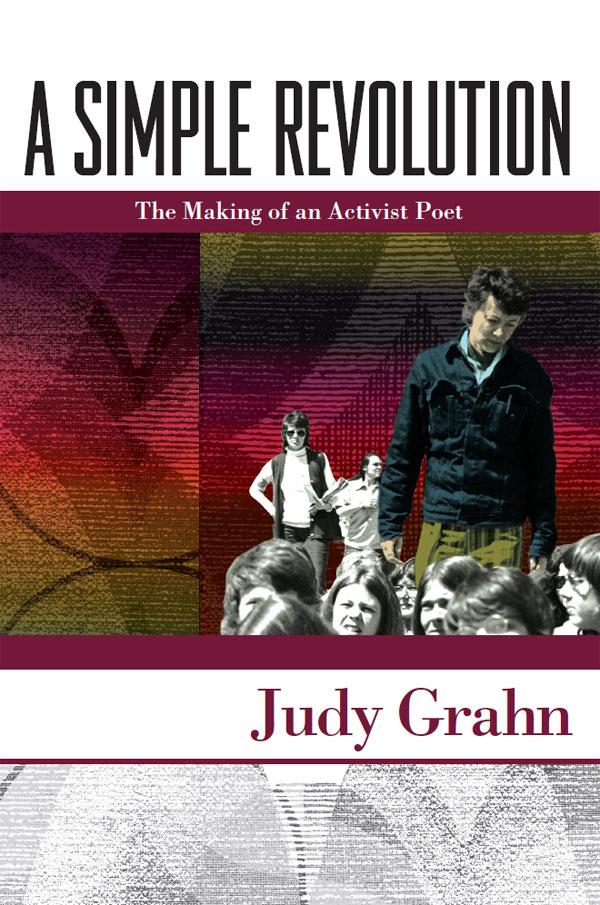

A SIMPLE REVOLUTION

The Making of an Activist Poet

Judy Grahn

aunt lute books san francisco

Copyright 2012 Judy Grahn

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Aunt Lute

Books P.O. Box 410687

San Francisco, CA 94141

www.auntlute.com

Cover design: Amy Woloszyn, Amymade Graphic Design

Cover photo: Judy Grahn 1973 West Coast Lesbian Conference in LA,

Photo by Chana Wilson

Text design and typesetting: Amy Woloszyn, Amymade Graphic Design

Senior Editor: Joan Pinkvoss

Managing Editor: Shay Brawn

Production: Ellen French, Chenxing Han, Aileen Joy, Alexa Kelly, Jada Marsden, Soma Nath, Kara Owens, Erin Petersen, Shaun Salas

This book was funded in part by grants from the Sara and Two C-Dogs Foundation, the Vessel Foundation, and Horizons Foundation.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grahn, Judy, 1940

A simple revolution : the making of an activist poet / Judy Grahn

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Print ISBN 978-1-879960-87-9 (acid-free paper)

Ebook ISBN 978-1-939904-06-5

1. Grahn, Judy, 1940- 2. Women poets, American--Biography. 3. Lesbians--Biography. 4. Gay liberation movement--Biography. 5. Protest movements--United States--History--20th century--Biography. I. Title.

PS3557.R226Z46 2012

811.54--dc23

[B]

2012037980

Printed in the U.S.A. on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To all brave radicals past, present, and future

Contents

PREFACE

A memoir rests on a foundation of memory, that oozy and changeable bog, constructed more of feelings than sequences of events. Sorting for reality means conducting research, careful lists, double and triple checking. And still I cant seem to spell names correctly. More double checking, someone to come in behind me with an eye for detail, sentence structure, accuracy that matches intention.

I wanted to fill out the picture of my life in the 1970s more fully than one person can, because it was such a collective experience. It seemed inaccurate, and even arrogant to try to tell a group story using only my own limited memory. What if I garbled and misrepresented?

So I interviewed people, about twenty of them, drawing on their recollections, and pulling a few direct statements into the body of my own telling. I also have carefully mapped some Bay Area lesbian households, as they constituted a geography of interconnection, a kind of interlocking urban village, for a particular area and era of time.

Sometimes I joke that this book becomes in places a multiple personality memoir. But in the end the perspective is mine, guided by my hopes that I have contributed to a fuller picture of the contributions of Northern California women to the mass movements of the Seventies, that younger folks find meaningful truths in this account, and that I have faithfully served that demon-lover: activist art.

Judy Grahn

CHILD OF THE WIND

We have to go to the press right now, something very bad has happenedweve been vandalized. I looked up, startled at the urgency in my lovers face as she burst into the living room.

The press was on Market Street in Oakland. The year was 1977. I felt numb and unreal as we walked through the factory-sized plant we had so painstakingly built up. The other press members were already inside the cavernous building. They walked with us through room after room, showing us the devastation, the blood drained from their faces. We stepped carefully over thick trails of black ink. The gooey stuff pooled on stacks of freshly printed books and saturated our precious papers. A wide heap of shredded graph paper and film, two feet high, lay outside the darkroomthe early production stages of six books. The black rollers of our printing presses, usually gleaming, were covered in abrasive, grainy powder.

Who did this? Everyone had a different idea, but all agreed it was a violent attempt to annihilate our enterprise, the largest womens press in the country. We stared at each other. We talked fast. Was it the FBI? Was it cops? How did they get past the alarm system? What should we do? My heart began to beat fast as my numbness flowed into heightened fear.

Casey stepped forward. No matter who they are, they might come back. We have to guard our plant.

They might set fire to it next time, someone else said, ratcheting up the tension.

We have a rifle and a pistol, Casey said. Well take turns staying up all night, two at a time.

So the next night I found myself in the darkened building, sitting side by side with my lover on a thin pallet. We shivered on the cold cement floor, staring at the dancing shadows of the leaves through the skylight, waiting for something more sinister to show its face. I wondered how, after I had given up guns, decided that violence did not suit our revolution at all, how was it that I held a rifle across my lap?

CHICAGO, 1949

I looked around in a dither. We were in a room filled with human heads that came into focus one expressive, unique face at a time. As I craned my neck and stood on tiptoe, my eight-year-old eyes absorbed the variety like food for my expanding heart. How one set of eyes was totally round, the next persons eyes were modulated with almond shaped eyelids, the next had eyelids with an extra fold near the nose, like mine, yet not like mine, as the skin tones varied as much as the shapes. And the hair! I had never seen such amazing hair, now shaped into butterfly wings, now kinky short and held in place with a thin string of beads, now braided, spilling down an imaginary back. How had creation accomplished this? Who were all these folks and where did they live?

I wanted to know them all. How did they speak? What were they thinking about?

My mother and I, a modestly dressed white woman and a bright-eyed white tomboy, had just walked into The Hall of the Races of Man at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in early 1949. This was one of two places my mother took me before we left Chicagothe other being the Brookfield Zoo. She wanted me to remember something of what the great city had to offer.

Look, Judy, my mother said with great excitement. Here are people who live everywhere on earth, all the people who live here on the planet. Isnt this amazing?

Well, not quite everyone. But here in the huge museum room, over a hundred fascinating faces and a few bodies of individual women and men beamed into life, sculptures of human beings from across the globe, each unique in shape, color, expression, age, and emotion.

Can you imagine making all these pieces? My mothers black eyes were wide with wonder. The sculptures were splendid, even miraculous, and aroused in me a powerful desire to know all the beautiful faces on earth, to actually meet these shining people. A dark-skinned man standing with his bare feet apart, holding a bow, a brown-skinned woman intently scanning the horizon of a marketplace or a sheep herd or a fishing village, a light-skinned woman with her hair piled in mountain-shaped waves or hung long in braids. The sculptors fingers had shaped their individuality into the forms, making normal the dignity of their lives, of their work. Lives and work so completely different from anyone we knew in Chicago.