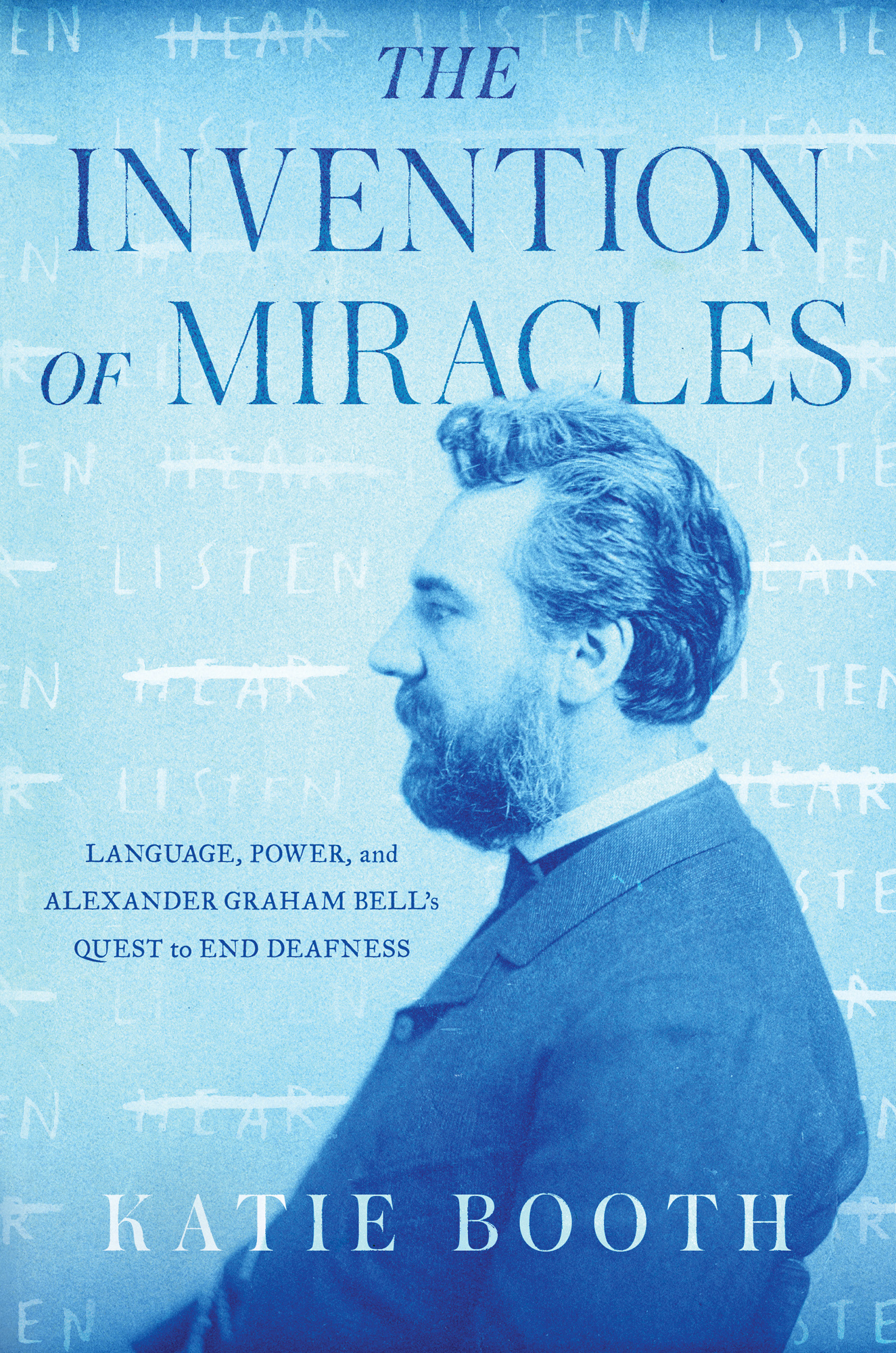

The Invention of Miracles

Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bells Quest to End Deafness

Katie Booth

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Katie Booth

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition April 2021

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

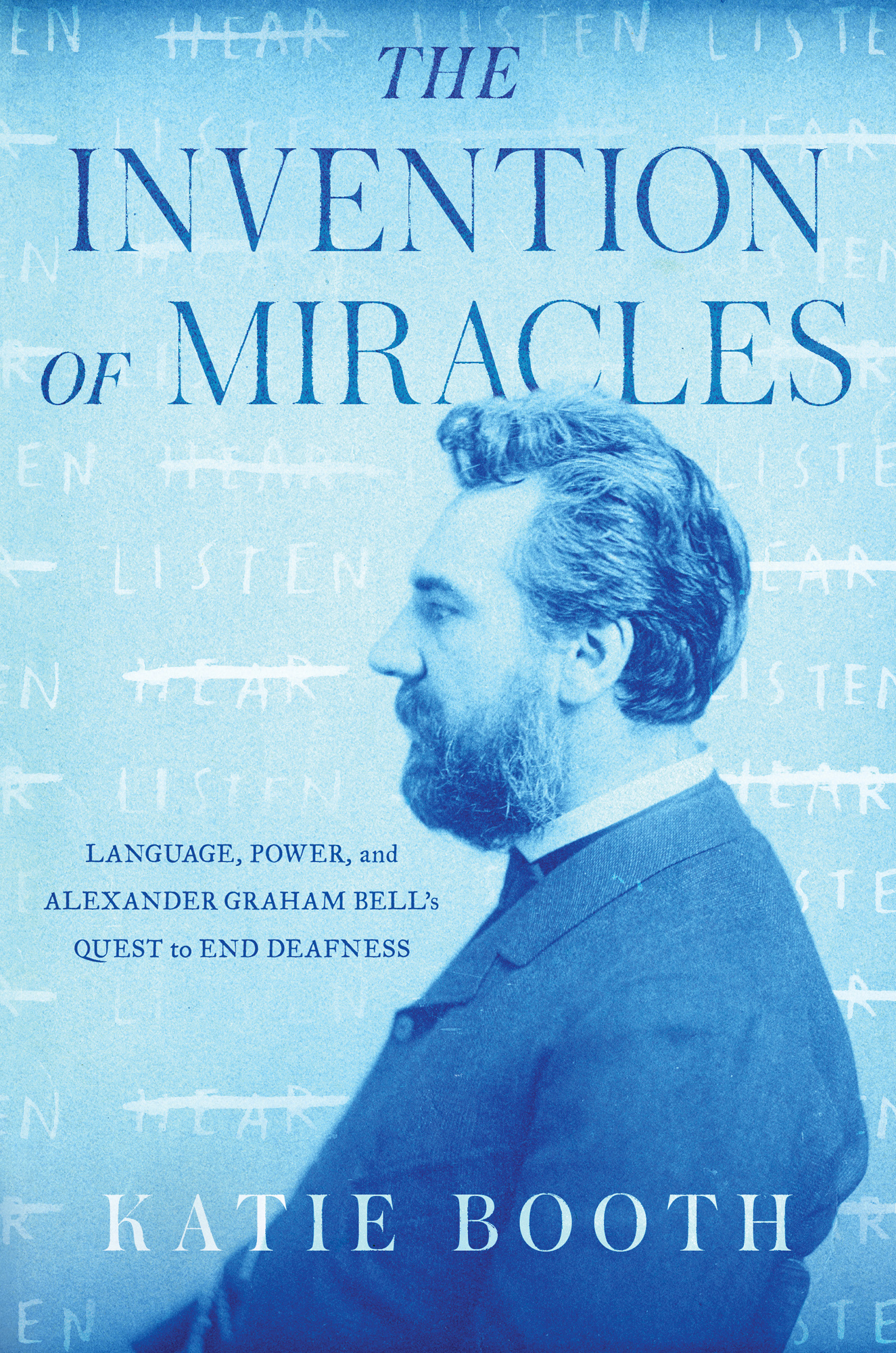

Jacket design by Math Monahan

Jacket photograph: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image Sia20212-1089

Jacket artwork by Christine Sun Kim; Originally Made as a Postcard (10X15Cm) for Primary Information (2017)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Booth, Katie (Writing instructor), author.

Title: The invention of miracles : language, power, and Alexander Graham

Bells quest to end deafness / Katie Booth.

Description: New York : Simon & Schuster, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020040764 (print) | LCCN 2020040765 (ebook) | ISBN

9781501167096 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501167102 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Bell, Alexander Graham, 1847-1922. | DeafMeans of communicationUnited StatesHistory. | SpeechStudy and teachingUnited StatesHistory. | DeafEducationUnited

StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HV2426.B39 B66 2021 (print) | LCC HV2426.B39 (ebook) | DDC 362.4/283dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040764

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040765

ISBN 978-1-5011-6709-6

ISBN 978-1-5011-6710-2 (ebook)

For

Harry McCarthy, Rose McCarthy,

and Rita Cyr

On Miracles

I n 1679, the first recorded attempt to teach speech to a deaf child in America was cut short by the local church, due to concerns that the teacher was committing blasphemy by trying to perform a miracle.

Two hundred years later, Alexander Graham Bells own work to teach the deaf to speak would be called miraculous, over and over again.

But a miracle hinges on what remains hidden.

Prologue

I n the hospital bed, my grandmother faced the window, bathed in the bluish light of the rising moon. I watched her body, memorizing it: the wrinkles of her fingers, the way her jawbone tucked back into her neck, the way her tongue moved like a soft oyster in the shell of her mouth. I had known her my whole life, but I had never before seen her weak. Now it was hard to look at her. The roundness of her body, which once seemed so soft and warm, was only heavy, seemed only to pin her to that hospital bed. Her usual facial expressioneyes sharp, mouth firmwas now tired, resigned. Her head lay on the pillow; her gray hair, thin and oily, was swept back from her face; her eyes were blank and dark. She wasnt dead, not yet, but something had shifted.

Normally I saw my grandmother in her home, among her deaf community, where apartments were set up with blinking lights for alarms, where telephones released little scrolls of typed English, and where furniture was arranged for open sightlines in order to use American Sign Language (ASL) across rooms. She lived among the culturally deaf, defined by the use of ASL and observation of deaf cultural norms. In those spaces, my grandmother had more access to information than I did. With friends she communicated in quick, fluent ASL, and even when I could catch the gist of the individual words I could also tell that there were layers and layers of meaning that were escaping me. They were carried in a small twitch of an eyebrow, the subtle lift of the corner of a lip, an invasion of space, or a quick shift away. In her world, she was firm, strong, steady. But here in the hospital, things were different.

My grandmother had suffered her heart attack four days before and had been in the hospital, alone, for the three days that followed. Only then did anyone get in touch with our family. In the meantime, my grandmothers presence barely seemed to have registered. My grandmother, through notes scrawled in English, had made several requestsfew of which seemed to have been addressed. She asked for someone to contact us, and for a TTY, a text-based telephone device, so she could call us herself. They gave her a TTY but ignored her insistence that it was broken. My grandmother had asked for an interpreter at least four times before we arrived, and received one only once, when the cardiologist came to see her. Even then, she misunderstood her diagnosisshe had no idea of the severity of the situation, the damage that had been done to her heart. With almost no information, she went on waiting for us. For those three days, we had no idea that she was lying there.

I was nineteen at the time and knew that a deaf family member in the hospital was an all-hands-on-deck situation. When I got the call, I took a late-night Greyhound back home from college and accompanied my mother to the hospital the next morning.

In this environment, I had access that my grandmother didnt, and the fact sat uneasily in my stomach. As I watched my grandmother, I listened for my mothers voice as she spoke to the doctors and nurses in the hallway. I couldnt hear her sentences, but I could hear the way her sounds began gently and then rose firm in advocacy. My mother knew the hospital staff would listen to her because they always turned to the hearing family members in these moments. They wrongfully saw us as the interpreters, caretakers, decision makers. Without us, they behaved as though there was simply no one with whom to communicate.

It happened everywhere. When strangers realized my grandmother was deaf, their faces contorted with discomfort or gawking fascination. Their bodies became stiff, moved away from her. They made mistakes. At restaurants, waiters were too flustered to serve her. When they did, chances were small that she would get what she had asked for, even though she knew how to point clearly at items on a menu and write any additional requests in her memo pad for them to read. At the mall, cashiers always forgot to remove security tags, and so she always set off alarms that she couldnt hear. She was chased down by security guards, who placed their hands angrily on her shocked arms before she had any idea what was happening.

Here, at the hospital, doctors and nurses did what they pleased with her body. Often they didnt look at her face at all. They avoided her eyes, which were hungry for information and seemed to embarrass them. If they spoke to her, they held their eyes big and moved their mouths in long, round shapes. They seemed to think that their distorted mouths could substitute for a certified interpreter, but my grandmother could make little meaning out of the charade. They ended with saccharine smiles, like everything was okay now, and then tugged at her arms, stuck needles into her veins, or rolled her bed to the operating room for open-heart surgery. Mostly, they spoke to one another. Their faces hovered intermittently above her and then, always, they turned away.