Acknowledgements

It is often said it takes a village to raise a child, I think the same applies to writing a book.

Thank you first and foremost to my wonderful editor, Sam Carter, and the team at Oneworld for taking a chance on John of Gaunt and on me, as an author in my infancy. Over the last three years you have nurtured me, steered me in the right direction and been enormously kind and patient. I couldnt have asked for a better publisher. Thank you to Rachel Mills, the best agent I could ask for, who has been with me throughout the whole journey. You listened to me wax lyrical about John of Gaunt and medieval history and you have waved my flag thereafter thank you, always. Dan Jones, thank you for coffee in Battersea, telling me to write this book, for generally being at the end of the phone or email when I need your advice, and for your abundant kindness and encouragement to myself and others.

Thank you to everyone who has at some point over the last three years offered me a few days or a few hours of childcare in order to write. Imogen, Julia, Sarah and Sam, Tom, Carys, Dad and Debbie, thank you for that crucial help even if it was just pushing the pram around the park whilst I scribbled.

Thank you to Jan Cooper, for taking the time to show me around Kenilworth Castle and for your expertise. It was a highlight in my research and enormously helpful to bring colour to John of Gaunts world. Thank you especially to Sean Cunningham, Head of Medieval Records at the National Archives, for helping me dig and for brilliant conversation as we got our hands dirty. Thank you Laura Tompkins for sharing your extensive research on Alice Perrers, I am so grateful for your generosity and time. Thank you to Holy Trinity Church in Rothwell, the convenors of the Institute of Historical Research Medieval Seminar and the staff at the London Library, the British Library, the Park Theatre and Hot Numbers, for keeping me well supplied with conversation, books, wine and coffee.

To the amazing community of historians who have been an enormous support along the way. There are too many of you to name all, but in particular; Joanne Paul, Estelle Paranque, Rebecca Rideal, Emma Wells, Dan Snow, Suzannah Lipscomb and Sophie Ambler.

I must acknowledge the memory of my dearest grandparents who passed away during the writing of this book and who would have been so proud to hold it: thank you for being constant and kind. In memory of Patricia Fickling; may you, inimitable lady, rest in peace. Finally, in memory of Professor W. Mark Ormrod, whose expertise on Edward III shaped much of my understanding of the fourteenth century: I am so grateful.

Thank you to my siblings; Hayley, Tom and Imogen for your endless support. To my daughter, Effie, for being the light of my life. And to my darling husband, Henry, whose unbending kindness, love, encouragement, lions share of dishwashing and bed-time routine, plus well-timed offers of sustenance, enabled me to complete this book I couldnt be more grateful for you, nor could I have done it without you. Thank you so much to my Mum, who has always taught me that anything is possible, because, why not? Lastly, thank you to my Pa, for trudging around castles, museums and mounds with me over the last three decades. This book could not have been conceived without those ramblings and your enduring support thereafter. It is only appropriate that this is dedicated to you.

Helen Carr, November 2020

A Note on Sources

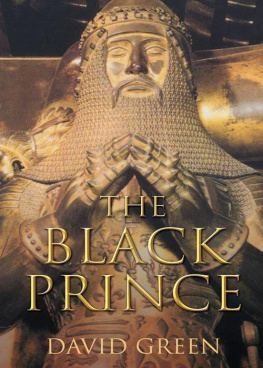

There have been two scholarly biographies of John of Gaunt. The first, written by Sydney Armitage-Smith in 1904, and the second, by Anthony Goodman in 1992. Armitage-Smith led the vanguard in unearthing the body of documents relating to John of Gaunt. He transcribed, translated and published John of Gaunts Register his roster of accounts: a crucial source on his life and movements as the Duke of Lancaster. Anthony Goodman provides a thorough analysis of John of Gaunts life, looking meticulously at his movements, politics and ambitions in impeccable detail a crucial starting-point for this book. W. Mark Ormrods work on Edward III and the political landscape of the fourteenth century has also been essential reading. Professor Ormrod has offered smooth explanations on complex medieval politics, for which I am grateful. Equally, Michael Joness excellent biography of the Black Prince has shed new light on the life and times of the world-famous Prince. I am indebted to Dr Joness new research on the siege of Limoges, which I discuss in the book. In unpacking the complexities and nuances around the war in France, I have relied on the excellent series on the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption. The colour, detail and even humour that leaps off the pages of his books enabled me to unpack how the ongoing war with France might have affected John of Gaunt.

Of the original sources available for Gaunt, his Register is the most insightful. It is preserved in the National Archives as part of the Records of the Duchy of Lancaster, PRO 30/14. Two hundred and thirty-five folios (pages) of original manuscript are bound in vellum in a large volume, around thirty centimetres in length and twenty centimetres wide. Inside the two volumes that make up the complete register are a series of documents with names and dates listed in the margins, that were copied by Lancastrian clerks and passed under John of Gaunts Privy Seal his personal seal, akin to a signature. The Register is a crucial piece of evidence in understanding Gaunts movements, the management of his land and property, and his relationships. There is information concerning the most senior members of his household his council which included a chancellor, a steward, a chamberlain, a controller and a receiver. There is also information on his treasurer, castle constables, grooms, cooks, carpenters, minstrels, falconer, gardener and armourers. The Register discloses information about Gaunts personal life in the gifts and grants he gave to family, loyal retainers, the church and his wives and mistress, and provides the greatest source of information on Lancastrian administration. The Register sheds more light on John of Gaunts personal activity and decision-making than any other source available.

Other administrative records that have been crucial in my research are the Parliamentary Rolls, the Calendar of Close Rolls and Calendar of Patent Rolls and the Inquisitions Post Mortem in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II, amongst others. All of these are helpful in analysing the political landscape of the fourteenth century that John of Gaunt spent the majority of his life successfully, and unsuccessfully navigating. At the National Archives in Kew are the Duchy of Lancaster records which I have rifled through resulting in black fingertips and a sneeze. John of Gaunts personal seals, also held at the National Archives, provide a visual representation of his rise to power notably in the change of his seal to include the arms of Castile and Leon.

The most colourful description of Gaunts world comes from the chronicle accounts of the period. Chroniclers were historians often clerical who described events in chronological order. The archetypal image of a chronicler is a monk or scribe clutching a quill and inking colourful manuscripts but, by the fourteenth century, a chronicler could also be secular and attached to a great household as a clerk.

The chronicles covering John of Gaunts early years were largely focused on the war with France and give detailed accounts of the battles and campaigns that took place. Jean le Bel was a French soldier from Liege and one of the early chroniclers to write in French rather than in Latin. Of all the chronicle accounts, his was largely reliable. As a solider, he travelled to England and Scotland and often wrote from personal experience. When he was not present, he did acquire good eyewitness accounts. Le Bel was a canon at Liege Cathedral, whose clergy were heavily involved in the practice and preparation of war, where he gathered much of his information.

Next page