The History of a

M EDIEVAL

M ISTRESS

J EANNETTE L UCRAFT

First published in 2006

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2006, 2010, 2011

All rights reserved

Jeannette Lucraft, 2006, 2010, 2011

The right of Jeannette Lucraft, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law.Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6828 0

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6829 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

To my darling Mike

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the staff of the History Department at Huddersfield University, particularly Dr Tim Thornton, Dr Katherine Lewis and Dr Pat Cullum. I would also like to thank Dr Nicholas Bennett of Lincoln Cathedral for answering my queries on Katherines tomb.

Thanks and love must also go to my parents for all their support and encouragement, and to my wonderful husband, Mike, for his endless patience and unshakeable belief in me.

Abbreviations

| CCR | Calendar of Close Rolls |

| CFR | Calendar of Fine Rolls |

| CPR | Calendar of Patent Rolls |

| DNB | Dictionary of National Biography, ed. Sidney Lee (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 188598) |

| JGR 13726 | John of Gaunts Register 13721376, ed. Sydney Armitage-Smith (London, 1911) |

| JGR 137983 | John of Gaunts Register 13791383, ed. Sydney Armitage-Smith (London, 1937) |

Introduction

The prioress twisted around to look at her charge, and thought that Katherine would do Sheppey credit. The girl had grown beautiful. That fact the convent perhaps could not lay claim to, except that they had obviously fed her well; but her gentle manners, her daintiness in eating these would please the Queen as much as Katherines education might startle her. Katherine could spin, embroider and brew simples, of course; she could sing plain chant with the nuns, and indeed had a pure golden voice so natural and rich that the novice-mistress frequently had to remind her to intone low through her nose, as was seemly. But more than that, Katherine could read both French and English because Sir Osbert, the nuns priest, had taken the pains to teach her, averring that she was twice as quick to learn as any of the novices. He had also taught her a little astrology and the use of the abacus...1

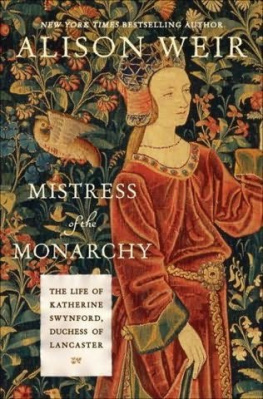

T his is the Katherine Swynford known to millions through Anya Setons novel, the medieval heroine waiting for her knight in shining armour, strengthened by some surprisingly modern female attributes of independence and self-reliance. But how close is the novels depiction to the real Katherine Swynford? Was she this heroine, skilful and intelligent, yet remaining very much the medieval feminine ideal, gentle, courteous and beautiful?

Goodman claims that Katherine Swynford is one of the most famous, enigmatic and controversial of medieval women.2 Enigmatic she certainly is. Goodmans is the only work of any length that seeks to uncover the real Katherine, and then his work is limited to a pamphlet of about 6,000 words. Any other work on her is brief to say the least. Famous yes, almost entirely because of Setons novel. First published in the 1950s, it still remains amazingly popular, still in print and appearing a respectable ninety-fifth in the BBCs Big Read initiative. Controversial well, she was fodder for the medieval equivalent of the tabloid press, and the position of royal mistress is still one that courts controversy. Television channels, newspapers and Internet sites the world over discussed the recent marriage of Prince Charles and his long-term mistress Camilla Parker-Bowles, conducting opinion polls on the public perception of this scarlet woman who so blatantly continued her relationship with the man she clearly loves in complete disregard for the fact that the public preferred his wife.

Indeed, there are remarkable parallels to be drawn between Katherines relationship with John of Gaunt and that of Charles and Camilla. Both are enduring relationships that, while not exactly conducted in secret, were not publicly recognised as official. Both couples were seen by some as flaunting their affairs in an undignified manner. The popularity of John, Duke of Lancaster, and Charles, Prince of Wales, has waxed and waned repeatedly, and the presence of Katherine and Camilla has affected the public perception of the two men. Charless first wife, Diana, was the archetypal blue-eyed blonde beauty much loved by the British public; so too was Gaunts first wife, Blanche. Both Charles and Diana, and John and Blanche, were viewed as golden couples; the popularity of both men was possibly at the highest during these marriages.

But, as much as the public wanted these relationships to be love matches, it is clear that in both cases the love match was with the mistress. Diana was eminently suitable to be a future queen, young, virginal, beautiful, from the right background and it is perhaps not too cold-hearted to say that it was this suitability for position that was the leading attraction for Charles. Likewise with John and Blanche. Blanche too was young, undoubtedly a virgin, beautiful, from the right background, English in the extreme and she just happened to bring a very attractive dowry in the form of the Lancastrian heritage. Whatever emotional feeling Gaunt had towards Blanche, the power that she brought him, a third son with little hope of securing power through the inheritance of the throne, was surely the leading attraction.

The parallel continues in the fact that both Diana and Blanche died tragically young. After the death of these women, the illicit relationships became increasingly public, until both men felt able to marry their mistresses. Gaunt had reached the end of his political career, and therefore the scandal of the marriage could not harm him in any real sense. Charles, however, has his main career, that of king, still ahead of him. His decision to marry has more potential to harm than Gaunts marriage. Perhaps Gaunt showed more prudence in waiting, despite his obviously deep love for Katherine. And Katherine obviously understood that, for Gaunt, duty had to come first.

So Goodmans claim is correct: Katherine is enigmatic, famous and controversial. But what else can be said about her? The aim of this book is to reveal more of the real Katherine Swynford. There are obstacles in the way, notably a lack of evidence for her life. Her will is frustratingly, and curiously, unavailable. The bequests made by Katherines contemporaries and peers fill the usual sources for medieval wills. A process of probate was undertaken, yet, mysteriously, Katherines will was never recorded. No personal letters or diaries remain for us to use to establish her personality. Her thoughts and feelings are not available. Her record as documented in the past is connected to her famous and powerful lover. In the vast documentary collection of the Lancastrian empire under John of Gaunt, glimpses of Katherine can be seen, as they can in the records of her Beaufort children with Gaunt, and the records of Gaunts son Henry IV. It is in this sense that any trace of Katherine is found in academic, historical publications. She is the appendage of other notables. Little credit is given to the idea that she was a real individual with her own life, and with the ability to control that life. In this book my hope is that the reader will indeed see Katherine as an individual, maybe one that is not too far removed from the romantic figure of Setons novel. Seton portrays Katherine as a strong character who desires to control her own destiny. I disagree with what that desired destiny was, but believe that this strong character with control of her life is more than just a fictional characterisation that it is one that has actual factual root.