1897 map by Edward Stanford showing the location of Charlotte Mews first two addresses, in Doughty Street (A) and Gordon Street (B).

Mew lived in this small area of London nearly all her life, moving just west of the Bloomsbury district in her last decade.

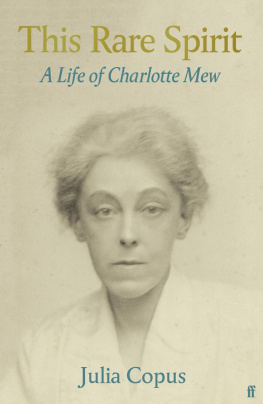

The Charlotte Mew I have come to know during the course of writing this book is quite different from the evanescent image I had in mind when I started, formed from a medley of information from the articles, websites, book chapters and theses I had read about her, as well as from two previous biographical accounts. One of these accounts is contained in an unpublished PhD thesis from 1960, by the American scholar Mary Davidow; the other by far the more widely influential is Penelope Fitzgeralds affectionate and absorbing portrait Charlotte Mew and Her Friends, first published in 1984. As I got deeper into my own research, I found a number of the preconceptions I had about Mews character and work altering out of all recognition.

Mew is perhaps best known for two things: she is the author of the much-anthologised poem The Farmers Bride, and she committed suicide while living alone in a single room in a street crowded with near-identical nursing homes. That much is true, and the gruesome manner of the death has continued to skew notions of who she was and how she lived her life, a distortion compounded by the fact that death itself is a recurrent motif in her poems and stories. It was the untimely loss to cancer of her beloved sister Anne that set the wheels in motion for the sad final weeks of Mews story. But in essence, her personality was rather different from that of the mythical tortured poet as her friend Alida Monro was at pains to point out when she introduced the first complete collection of Mews poems in 1953:

It must not be thought, as has been supposed by many who judge from Charlottes own writings, that she was always in a state

Even so, the end and the means of that end was no surprise to Mews friends when it came. Anne had been closer to her than anyone: they shared not only a particularly close sibling bond but the burden of safeguarding various family secrets and the experience of being clever and ambitious women (Anne was a painter) at a time when it wasnt seemly for women of their social class to be either. The author of Mews obituary in The Times, Sydney Cockerell, remarked that the pair had more than a little in them of what made another Charlotte and Anne, and their sister Emily, what they were.

Mews literary output was modest: a dozen stories and essays appeared in magazines, and twenty-eight poems were published in two editions of The Farmers Bride the only book to appear during her lifetime; a further thirty-two poems make up The Rambling Sailor, the collection that was issued a year after her death. In his obituary, Sydney Cockerell suggested many more poems had been written that had fallen prey to house moves, spells of depression and an over-zealous editorial eye: There can be no doubt that her fastidious self-criticism proved fatal to much work that was really good, and that the printed poems are far less than a tithe of what she composed. Anne was also present on that occasion, and it is an indication of Mews playful, and often inscrutable, nature that neither Anne nor Alida could decide whether the comment was made in jest, or if Mew really was destroying original work.

*

Charlotte Mew once commented on just how much of a person remains hidden even from ones nearest and dearest: So little do we people who spend our days together know each other! the real-life recipient of such passion might have been. We are used to knowing such things: in the case of many other writers of Mews era, the beloveds identity was either known at the time or was quickly brought to light by the most cursory biographical research. The emotional entanglements of T. S. Eliot, Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence, W. B. Yeats and Oscar Wilde, for instance, are all well documented. In Mews case, no trace survives (if it ever existed) of any romances in her life let alone of sexual encounters and nothing that could be described as a love letter, either to or from her, has been found.

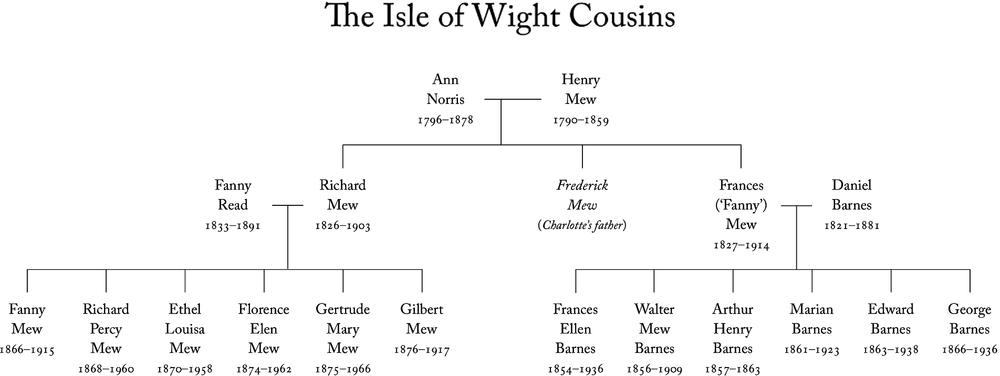

There was one rumour in circulation during her lifetime that hints at an early taste of romance, and that was retold by her avowed favourite cousin, Gertrude, to doctoral student Mary Davidow in the late 1950s. Gertrude revealed that there had been some sort of mutual attraction between Charlotte Mew and Sam Chick, the elder brother of the Chick sisters whom Charlotte knew from school. Still, it is possible that, despite the passion of her poetry, she was a virtual stranger to romance, though not to the romantic impulse. Her work is full of shared kisses, sea breezes, the intoxicating scent of hair, the wandering passion of lovers eyes and hands, and so on. She writes in the voices of male and female lovers alike. But the swarm of narratives that has amassed to fill the silence surrounding her romantic life and sexual preferences is almost wholly based on conjecture. The best known are those that recount Mews romantic attachments to three specific women, as outlined in Fitz geralds Charlotte Mew and Her Friends, but they are unsubstantiated and of doubtful origin. In the case of her friendship with short-story writer Ella DArcy, I have included a note at the foot of the main text at the point where my account differs most significantly from that given by Fitzgerald.

It is curious that, despite a dearth of information on the subject, the question of Mews sexuality has become so closely linked both with her identity and with her work, and the idea that she was unarguably lesbian has stuck. In Chapter 7 I consider how and why that idea first surfaced. Mew may have been attracted to women, or to men or indeed to both;

What is certain is that the difficult circumstances of Mews life meant there were many matters she prioritised over finding a sexual partner chief among which was the decision, according to Alida Monro, not to have children because she didnt want to pass on the familys strain of insanity. In nineteenth-century Britain, that decision would have made good sense: eugenics, and the idea of a responsibility to future generations, was at its height in the 1880s and 90s, just as Mew was coming into womanhood. The other choice she made was to put the wellbeing of her increasingly vulnerable family unit ahead of other considerations at every juncture. She was still in her twenties when, upon the death of her father, she effectively took on the mantle of head of the household, and her letters suggest that, from that time on, she was with the family for most hours of most days. Her daily life was filled with running the house, caring for her needy mother and her siblings, and arranging the familys legal and business affairs. If the desire for a sexual relationship did play a part in Mews life, it was a facet that she barely allowed to see the light, if at all.