After Every War

| FACING PAGES

| FACING PAGES

NICHOLAS JENKINS

Series Editor

HORACE, THE ODES

New Translations by Contemporary Poets,

edited by J. D. McClatchy

HOTHOUSES

Poems 1889,

by Maurice Maeterlinck,

translated by Richard Howard

LANDSCAPE WITH ROWERS

Poetry from the Netherlands,

translated and introduced by J. M. Coetzee

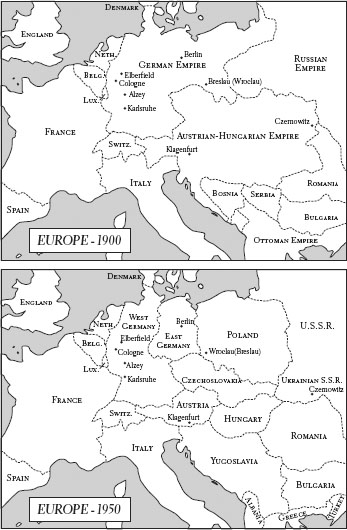

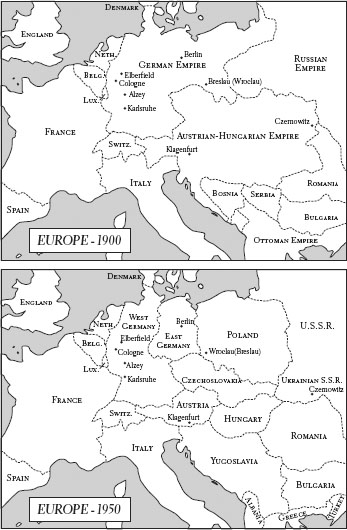

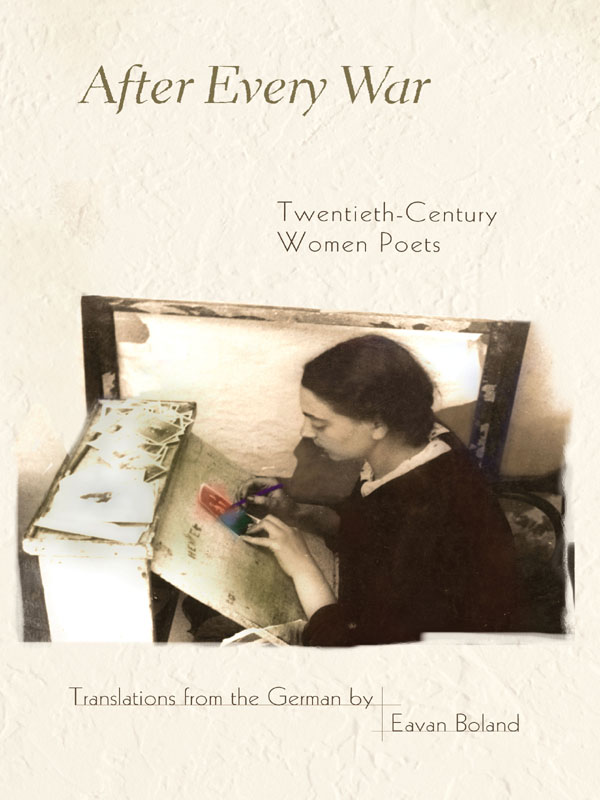

AFTER EVERY WAR

Twentieth-Century Women Poets,

translated from the German by Eavan Boland

After Every War

Twentieth-Century Women Poets

Translations from the German

by Eavan Boland

PRINCETON

UNIVERSITY

PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2004 by Eavan Boland

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

After every war : twentieth-century women poets / translations from the German by

Eavan Boland.

p. cm. (Facing pages)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-11745-4 (alk. paper)

1. German poetry20th centuryTranslations into English. 2. German poetryWomen authorsTranslations into English. I. Boland, Eavan.

II. Series.

PT1156.A38 2004

831'.910809287dc22 2003061014

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Electra LH

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The author acknowledges the following publishers for permission to translate from the German: Rose Auslnder: S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1990; Elisabeth Langgsser: er, Geist in den Sinnen behaust. Matthias-Grnewald-Verlag, Mainz 1951, Germany; Nelly Sachs: Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1961; Gertrud Kolmar: Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 1983; Else Lasker-Schler: Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 1996; Ingeborg Bachmann Piper Verlag and Zephyr Press (U.S.); Marie Luise Kaschnitz: Cassen Verlag, Mnchen, Germany; Hilde Domin: 1987 S. Fischer Verlag GmbH Frankfurt am Main; Dagmar Nick: Rimbaud Verlag. For photographs of the poets, the author gratefully acknowledges: S. Fischer Verlag (Rose Auslnder); Schiller-Nationalmuseum Deutsches Literaturearchiv (Elisabeth Langgsser); Suhrkamp Verlag (Nelly Sachs); Schiller-Nationalmuseum Deutsches Literaturearchiv (Gertrud Kolmar); Suhrkamp Verlag (Else Lasker-Schler); Renate von Mangoldt (Ingeborg Bachmann); Suhrkamp Verlag (Marie Luise Kaschnitz); S. Fischer Verlag (Hilde Domin); and Peter Peitsch/peitschophoto.com (Dagmar Nick)

TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHER

and her friendship with the Burghartz family

After every war somebody must clean up

WISAWA SZYMBORSKA

PLACES OF ORIGIN

After Every War

INTRODUCTION

I

When I was a child two German girls came to help my mother in the house. It was just after the war. The small towns of Germany were in the grip of winter, hunger, and disgrace. These girls, who were sisters, hardly more than teenagers, had left that aftermath behind and come to the shelter of a country which had been neutral. There was rationing in Ireland. But there was also butter and meat. Clothing was plentiful. It was an easier place to be.

I was too young to remember their actual arrival. They came into my consciousness with my first words, my first memories. I remember the kitchen, the damp clothes, the snap of the fire, the smell of peat. I remember one of them opening a door that led into the darkness of a back lane. I can hear their voices as they folded clothes and put away plates. I can hear my own voice as I said back the numbers they tried to teach me: eins zwei drei vier fnf. Over and over again. Or the quick phrases I learned because they spoke the reality of their lives. Ich bin beschftigt. I am busy.

Above all, I remember that when my parents left the room, and there was no need to learn or be polite, they spoke to each other in rapid, headlong sentences, shutting out with relief the Irish twilight, the small child, and all the evidence of what was not home.

For many years they were a background memory. Gradually, that changed. They became at once clearer and more mysterious: intaglios, cut deeper in my consciousness than I had realized. Even their voices began to return. What was it I had heard? Gossip and anecdote? Or was I hearing distant towns, in their harsh moment of reckoningand wider tragedies of nationhood and inhumanitycreeping through their words like fog under a windowsill?

The truth is I couldnt know: not then, not now. But some of the yearning and curiosity I still feel about them is in this book. It is the outcome of years of retrospection and regret, of knowing I had not asked them the questions I later wanted to ask. When I first saw them they were teenagers, sisters. Both are now dead.

But later it seemed that the door one of them opened was legendary, not realthat it led from our ordinary, teatime kitchen into the very heart of a broken Europe. And the conduit, the path was language. A language I could not understand but which spoke to me all the same.

It still speaks to methat language I cannot understand but need to hear. And that, I think, covers some of the paradox of translation. Some of the poems in this book were being written, or had been written, at the very moment those sisters were talking. In some of these lines their loneliness, their necessary absence is explained far more clearly than they or I could then have managed.

II

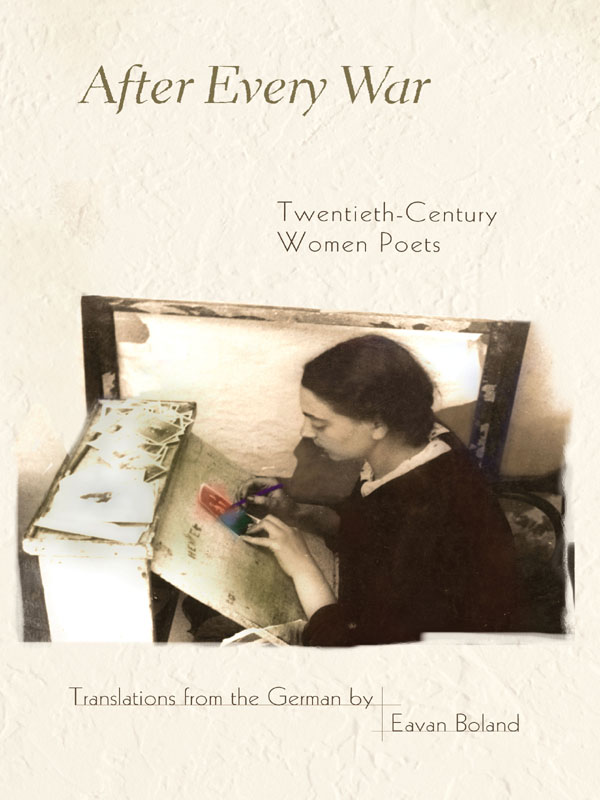

There are nine poets in this book. Their dates of birth range from the mid-nineteenth century to the first decades of the twentieth. All are German-speaking. Their places of origin are from as far north as Bukowina and as far south as Carinthia. Their places of exile range from Sweden to South America.

All wrote in the presence or aftermath of a war which cut deeply into their lives. Of course, they lived different lives and experienced the war variously. It also needs to be remembered that the poems here are only a fraction, albeit an important fraction, of the work written by these poets.

These are poems, then, written in the shadow of a war. But there is more to it than that. They are poems written by those whom war injures and excludes in a particular wayin other words, women. Nevertheless, the question may persist: why women, why war? If these look like restrictive categories for translation, there is a reason.

The problem with human catastrophe is that it can be remembered all too well. But it is much harder to re-imagine it. What brings it from the domain of fact to the realm of feeling is often just a detail. A cup, a shoe, an open window, a village roof with missing slates. Once we see it, we recognize it. That could have been me, we suddenly think. I could have been there. That moment of private truth, simply because it cuts history down to size, has a rare value.

It seems to me there is something compelling and revealing in the way the world of the public poet encounters the hidden life of the woman in these poems. As it does so, both change. The individual experience of the first makes the collective experience of the second available in a new and poignant way. The result is a dark, moving interplay of determinism and elegy.

Next page

| FACING PAGES

| FACING PAGES