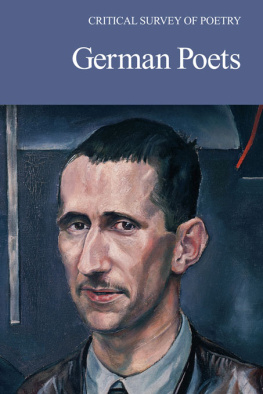

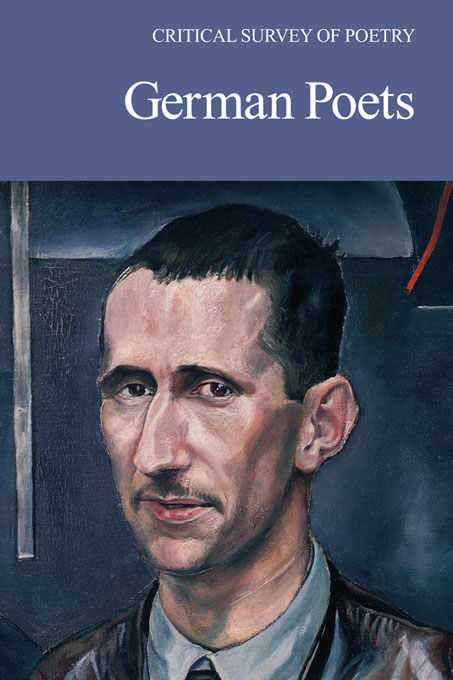

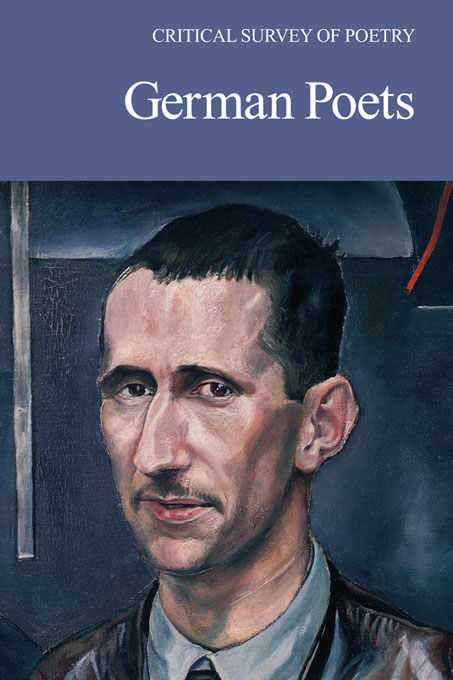

Cover photo:

Bertolt Brecht ( Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive/Corbis)

Copyright 2012, by Salem Press, A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc.

All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews or in the copying of images deemed to be freely licensed or in the public domain. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, at csr@salempress.com.

eISBN: 978-1-58765-910-2

CONTENTS

Robert Acker

University of Montana

Lowell A. Bangerter

University of Wyoming

Desiree Dreeuws

Sunland, California

Jack Ewing

Boise, Idaho

Donald P. Haase

Wayne State University

Todd C. Hanlin

University of Arkansas

Rebecca Kuzins

Pasadena, California

R. C. Lutz

CII Group

Laurence W. Mazzeno

Alvernia College

David J. Parent

Normal, Illinois

Margaret T. Peischl

Virginia Commonwealth University

Helene M. Kastinger Riley

Clemson University

Joachim Scholz

Washington College

Nancy E. Sherrod

Georgia Southern University

Jean M. Snook

Memorial University of Newfoundland

Richard Spuler

Rice University

Klaus Weissenberger

Rice University

Poetry as a pleasant distraction from life, as a conventional ornament for social occasions, as linguistic play or experiment, even as the sincere expression of heartfelt emotions, belongs to comparatively recent times. In its beginnings, humankind used the magical power of patterned, rhythmic speech to impose meaning and order on the world. Through poetry, humankind hoped to gain mastery of both the natural and the social environment. Certainly this was true of the Germanic tribes: The first writer to mention Germanic poetry, the Roman historian Tacitus (c. 55-120 C.E.), expressly refers to the Germanic custom of celebrating gods and heroes in song. Religion (humanitys relation to God) and history (humanitys relation to the community in time) were to remain poetrys central domain for centuries to come. Thus, the historical and cultural context can never become a matter of indifference to those who care for poetry. What might appear to later generations as mere background was related strictly to the purpose and theme of poetry in its own day. In ancient times, few deeds were unaccompanied by the poetic word, and fewer still would be remembered were it not for poetry.

Germanic tribes lived on the shores of the North and Baltic seas as early as 2000 B.C.E. Some time after 500 B.C.E., when climatic changes forced most of them to migrate south, they divided into three distinct groups. The North Germanic tribes (Normans, Danes, Jutes) were those that stayed behind; the East Germanic tribes (Goths, Vandals, Burgundians) slowly drifted southward into present-day Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria; and the West Germanic tribes (Saxons, Franks, Angles, Swabians, Alemanni) moved into the middle of Europe, present-day Germany, northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

The Germanic tribes had barely settled in their new environment when the Huns, a fierce Mongolian people, swept into Europe around 400 C.E. The impact of the Hunnish invasion was most directly felt by the East Germanic tribes. Pushed forward by the relentlessly advancing Huns, the Germanic tribes fell on an already tottering Roman civilization, gaining and losing power over the nations in their path with spectacular speed. The Vandals established kingdoms in Italy, Spain, and North Africa; the Goths, in Italy and Spain; the Burgundians, on the Rhine.

ORIGINS TO ELEVENTH CENTURY

Two hundred years later, these tribes had all but disappeared, exhausted and decimated by their heroic exploits, absorbed by the cultures and people they had overrun, yet they disappeared only after leaving behind a lasting record of their remarkable feats. If history demands patterned, poetic order, it certainly demanded it here, in the face of the splendid achievements and the tragic end of the East Germanic tribes. Soon, the scop, the warrior-poet, sang in the lords hall of heroic courage and loyalty, of betrayal and revenge, of inscrutable fate and mans fortitude when confronted with its cruel decrees. For centuries, this oral poetry informed and stimulated the imagination of the Germanic tribes until, several hundred years later, some accounts were finally given literary form.

Though naturally influenced by the tumultuous events around them, the West Germanic tribes underwent a gradual development. The most notable migratory action was that of the Angles and some of the Saxons, who, after the Roman forces had pulled out of Britain, began to settle there in the fifth and sixth centuries. On the Continent, historical progress took place under the steady ascendancy of the Franks. Clovis I (481-511) united all major West Germanic tribes, with the exception of the Continental Saxons, under Frankish leadership. When Clovis converted to Roman Catholicism, Latin culture quickly accompanied Christianity on its missionary journeys. The ensuing political and cultural unification was underscored by a growing linguistic unity among the tribes. Starting among the Alemanni of Germanys southern highlands, a consonant shift spread through the West Germanic tribes, differentiating their language from that of their North Germanic neighbors as well as that of the Angles and Saxons. This language, Old High German, is considered the first distinct forerunner of modern German.

The unity of the West Germanic tribes reached its culmination under the rule of Charlemagne (768-814). Charlemagne was not only a brilliant political leader but also a farsighted patron of the arts; the earliest extant literary fragments in the vernacular date from his reign. Baptismal vows, creeds, and prayers give evidence of the importance that church and state placed on the vernacular in their concerted effort to convert the Germanic peoples to Christianity. Nevertheless, cultural life under Charlemagne and his Carolingian successors proceeded mostly in Latin. Of lyric poetry in Old High German, only two fragments of poems have survived. Both are religious in nature, though secular poetry did exist, as is indicated by an ecclesiastical injunction against the writing or sending of Winileodos (songs of friendship). The Wessobrunner Gebet (c. 780; Wessobrunn Prayer) contains in twenty-eight lines a fragmentary account of creation, while the Muspilli (c. 830), almost four times as long, describes the Day of Judgment.

The most important poetic work of the ninth century, however, is an epic, the religious epic Der Heliand (c. 840; The Heliand, 1966). In its six thousand lines of dramatic alliterative verse, Christ has been transformed into a magnanimous Germanic lord and his apostles into retainers who, moving with him from castle to castle, believe in his mission with unflinching loyalty. Unfortunately, the epic did not have its deserved impact on German literature, because it was not written in Old High German, but in Old Low German (Old Saxon), a Germanic dialect as yet unassimilated by the developing German language. Thus, it was quickly forgotten and not rediscovered until, in the sixteenth century, the Protestant Reformation searched high and low for a historical tradition.

Next page