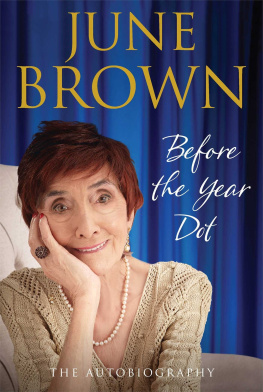

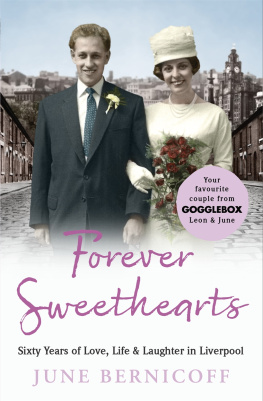

BEFORE THE YEAR DOT

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2013

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2013 by June Brown

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of June Brown to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-47110-182-3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-47110-183-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-47110-185-4

The author and publishers have made all reasonable efforts to contact copyright-holders for permission, and apologise for any omissions or errors in the form of credits given. Corrections may be made to future printings.

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Joy and woe are woven fine,

A clothing for the soul divine.

Auguries of Innocence by

William Blake, 1863

#xa0;

Oh, why should she who holds all my hopes of peace

Seek her peace with strangers

And increase the number of her failures?

Personal poem by

James Law Forsyth, 1948

Prologue

At sixteen I was very interested in palmistry. The fate line on my right palm had a distinct break at the age of thirty. It broke into two parts that ran for a quarter of an inch on parallel tracks. I used to look at it and wonder, What will happen to me when I am thirty that will change my life? Of course, it was Johnnys death. But, in fact, my life was changed twice by death.

I cant remember a time when Marise wasnt there (she was sixteen months older than me).

Junie, Junie, quick, get the cotton wool and the olive oil. My sister Micie (my name for her, pronounced Meecie) woke me early one morning in June 1934. I was seven years old.

She was sitting up beside me in the bed that we shared in the big attic of our flat over Fathers electrical business. The first floor had two main rooms a drawing room and a dining room that seemed enormous to me. There was a kitchen, a bathroom and two bedrooms; one where my parents slept and the other where my fathers canaries were kept in cages. They had had an aviary at our previous house in Warwick Road but the flat had no garden.

Micie and I were relegated to the attic, which, ironically considering Fathers business, had no electric light and we had to go to bed by candlelight. I was scared whenever I was sent up into the darkness to fetch our nightdresses in order for us to be able to undress downstairs in the light.

The attic frightened me because there was a trap door set in the floor. It opened up to reveal a disused, back staircase, which would have led straight from the maids attic bedroom to the kitchen, keeping her out of sight. We would wait in dread for this door to open, revealing some unknown terror.

I ran down the main staircase to the bathroom to fetch the olive oil and cotton wool a panacea for earache. I did not think to wake my mother.

Micie was put into my parents bed where Mother could care for her more easily. I wasnt aware that Micie was very ill. I can still see her sitting up in Mothers bed. I must have gone to say goodbye to her before I went to school. I have a memory of my granny going in to see her there and coming out saying, There is a dying child, but, do I remember it or did Mother tell me long afterwards? I know I have a picture of it in my mind.

A few days later, I came home from school and Micie wasnt there. She had been taken to Ipswich General Hospital for a mastoid operation.

Rosebud (Rosemary, our younger sister) and I never saw her again.

My mother did tell me, much later, how dreadful it was to hear Micie cry out when the dressings packing the wound behind her ear were drawn out and then replaced. Whether an infection was introduced through this, I dont know, but Micie developed meningitis, became paralysed and, a few days later, she died. Had she lived, she would have been permanently paralysed and would have spent her childhood in one of those long, wicker spinal carriages. Yet, Mother, who was with her, said that, just before she died, she suddenly sat up in bed, held out her arms and smiled.

Micie was a very spiritual child. In the hospital, she had asked Mother to bring her Bible to her. In contrast, she was also a tomboy. I wasnt. I was timid.

I cant remember a time at all when Micie wasnt there. I can see myself at school outside the classroom door saying to my teacher, Miss Downing in a very ordinary, prosaic voice, Micie died yesterday.

Her coffin lay in the darkened drawing room with the door closed. We never saw her, Rosebud and I. We just knew she was there.

On the day of the funeral, twelve-year-old Maggie Forsdyke had come to take care of us. She often used to come and play with us in the garden of our old house in Warwick Road and play our piano for us in the drawing room. Although she didnt know what the day was about, Rosebud, who was four, was aware of the atmosphere of misery and she started to cry. Rosebud didnt know why but she didnt want Maggie to play.

Micie was buried in the childrens section of Ipswich Cemetery. She was buried in my brother John Peters grave, who had died as a baby eighteen months before. She has a marble headstone, with angels on either side. Afterwards, we would walk to the cemetery to put flowers on the grave. In the winter, it was always chrysanthemums. I have never liked chrysanthemums since. Their smell reminds me. She and I had always shared a room, walked to school together and were hardly ever apart. Had she lived, we would have been in the same class at school, as I was to jump a class that summer, being clever as a child. Suddenly I was on my own. There was Rosebud, of course, but she was only four, and so was not much of a companion to me. She was a dear little girl but we were never as close as Micie and I had been.

Micie was born on the 6 October 1925, and died in June, 1934. Had antibiotics been available, there would have been no operation, she would not have died and, consequently, my life would have been quite different.

The loss of her affected my whole character and shaped the way I behaved for a long time. In particular, it influenced my expectations of men. Too dependent, I found it impossible to be happy alone. I was constantly in and out of love, always looking for the kind of caring that Micie had given me the wholehearted acceptance of me just as I was. I kept looking for the friend I had lost.

I wanted to share everything as I had for the first seven years of my life. I found that companionship for a while, when I married my first husband Johnny. He was a great sharer and he did look after me and, in many ways, I looked after him.

I can be happy on my own now. Ive learnt how to be.

Having written that I realise that Im not being entirely truthful. After ten years of being a widow I would still like to share thoughts, laughter, meals, visits to the theatre, problems, house repairs! Not a husband nor a lover do I want. Just a compatible companion.

Chapter One

We moved very quickly after Marises funeral to a semidetached house in Grove Lane. Moving into this unfamiliar, gloomy house with its dark bare attics disorientated me further. It never seemed to feel or see the sun. Mother must have found the memory of Marise sitting up in her bed, seemingly not seriously ill and so soon afterwards lying in her coffin in the drawing room, too much to bear.