CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

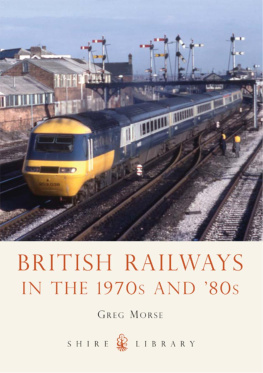

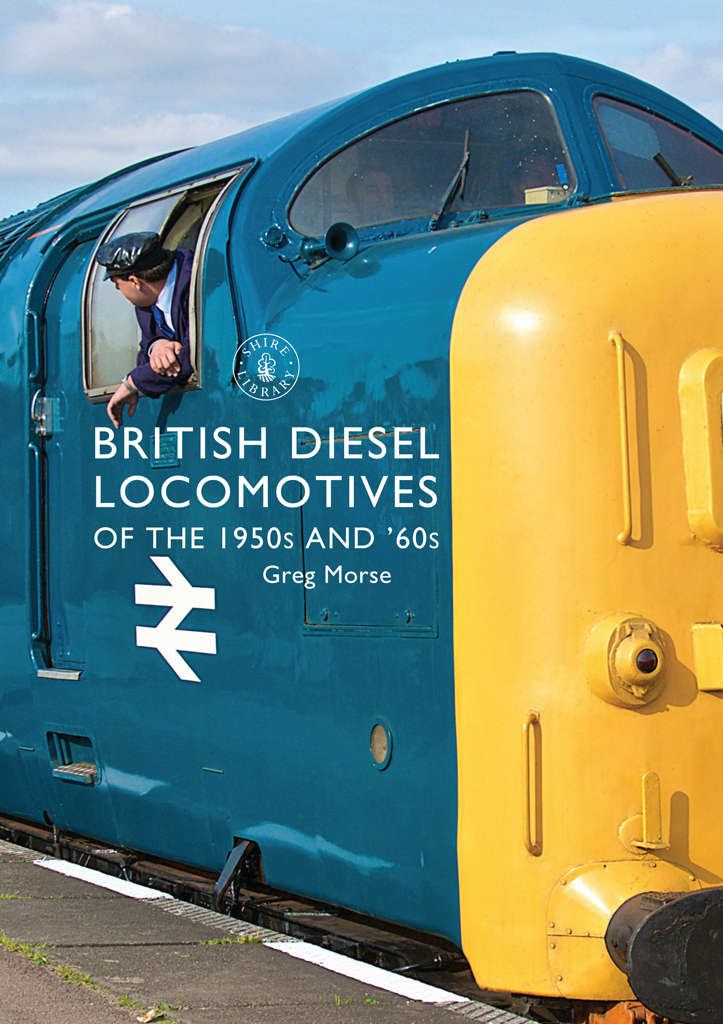

Ive seen some of these loco drivers climbing into a diesel as if it was the grave.

So said the narrator of the British Transport Films recruitment short A Future on Rail in 1957. Though the idea was to show the positive aspects of modernisation these drivers soon learn to enjoy the comforts of the cab after the toil and heat and sweat of the footplate the truth was that many men left the industry for good when forced to leave steam behind. And why not? Steam engines breathed; diesels were just boxes on wheels you got in, pushed a button and off you went. It just wasnt the same. There just wasnt the dignity the heroism in this brave new world. Not that it was all that new

At Guildford in 1963, ex-Southern N class no. 31870 waits while a porter takes a barrow of parcels up the platform a world of tradition that would soon change for ever.

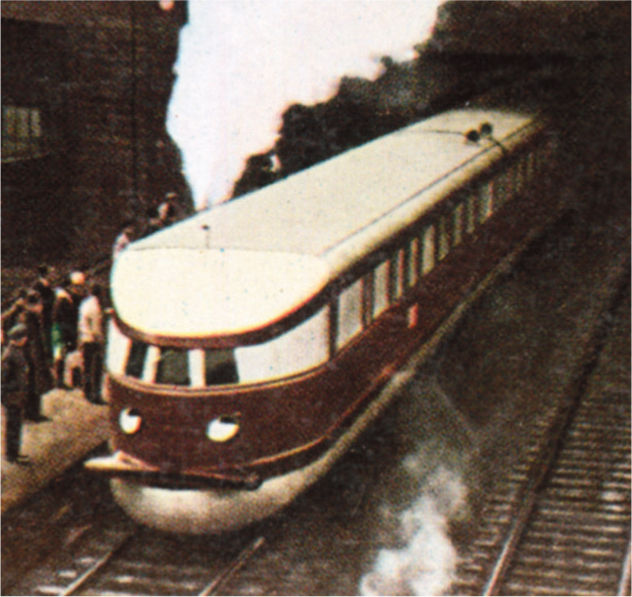

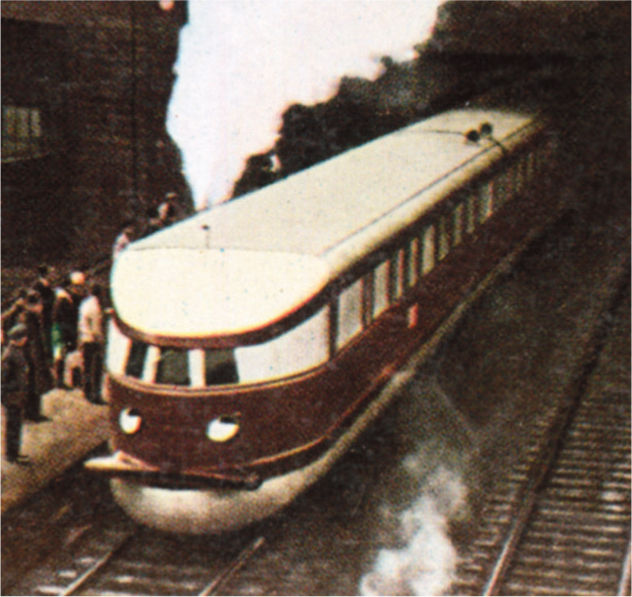

The German State Railways SVT 877 the Fliegender Hamburger was launched in 1933 and reached 100mph in service.

Invented in 1892, the diesel engine was first used to power a railway vehicle in 1912. Initial trials werent terribly successful, but a breakthrough came two years later when American giant General Electric produced a reliable control system. By 1929, Newcastle-based Armstrong Whitworth was building diesel-electric locomotives for Argentina, but in 1933 the German State Railway launched SVT 877 the Fliegender Hamburger a unit train that demonstrated the technologys true potential by reaching 100mph in service.

The elegant Art Deco lines of GWR railcar no. 4, built by AEC and introduced to traffic in 1934.

British railway companies were a little slower off the mark: the London Midland & Scottish had dipped a tentative toe in the water in 1927 with the production of a diesel railcar, but around the time the SVT 877 was taking off, another Armstrong Whitworth locomotive was being tested to no great success on the London & North Eastern. It and the Great Western would also experiment with diesel railcars, but while each of the Big Four the GW, LMS, LNER and Southern would explore the possibilities of diesel shunters, steam remained dominant, and it was not until after the Second World War that engineers started to think more deeply about putting internal combustion engines to heavy main-line use.

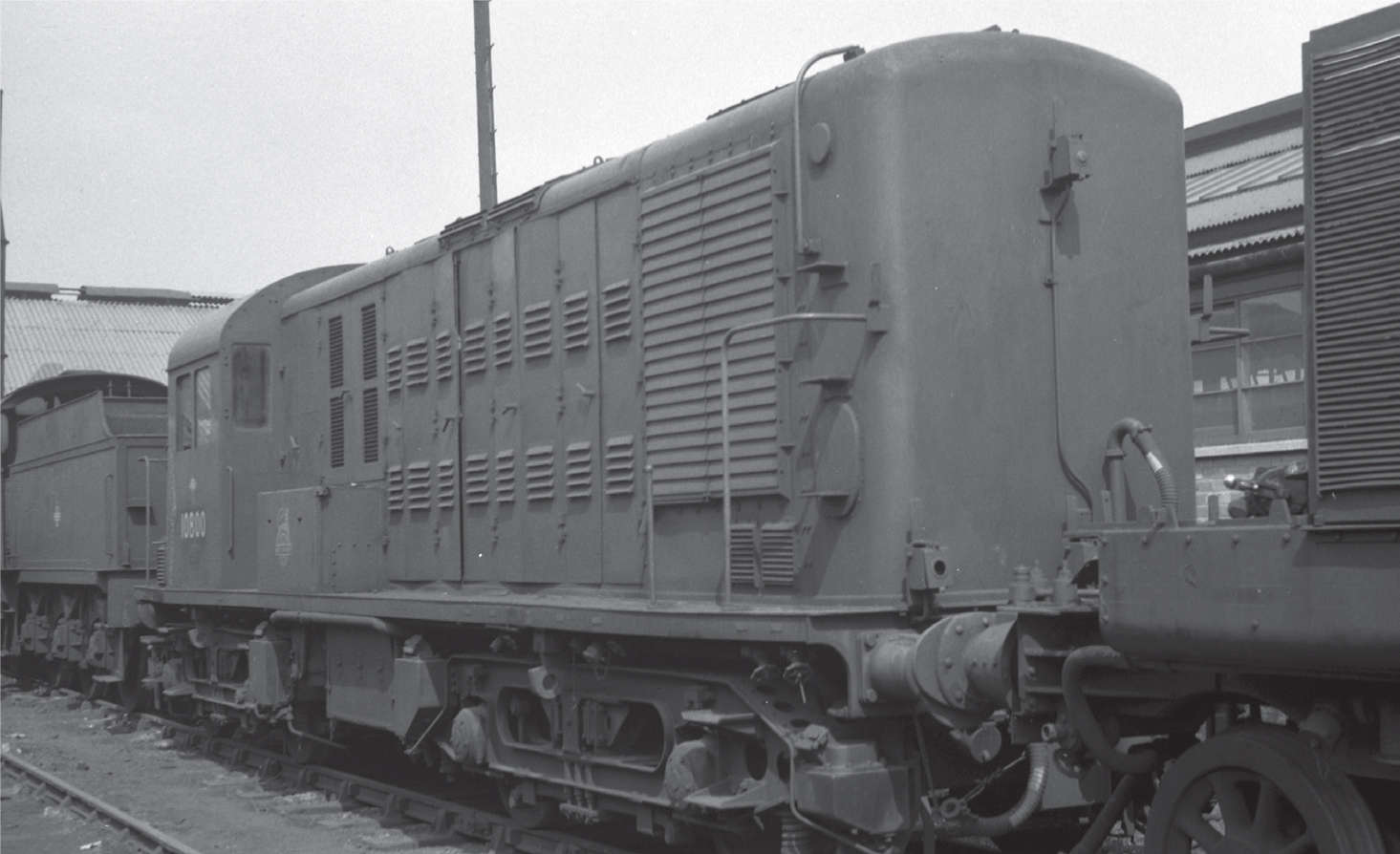

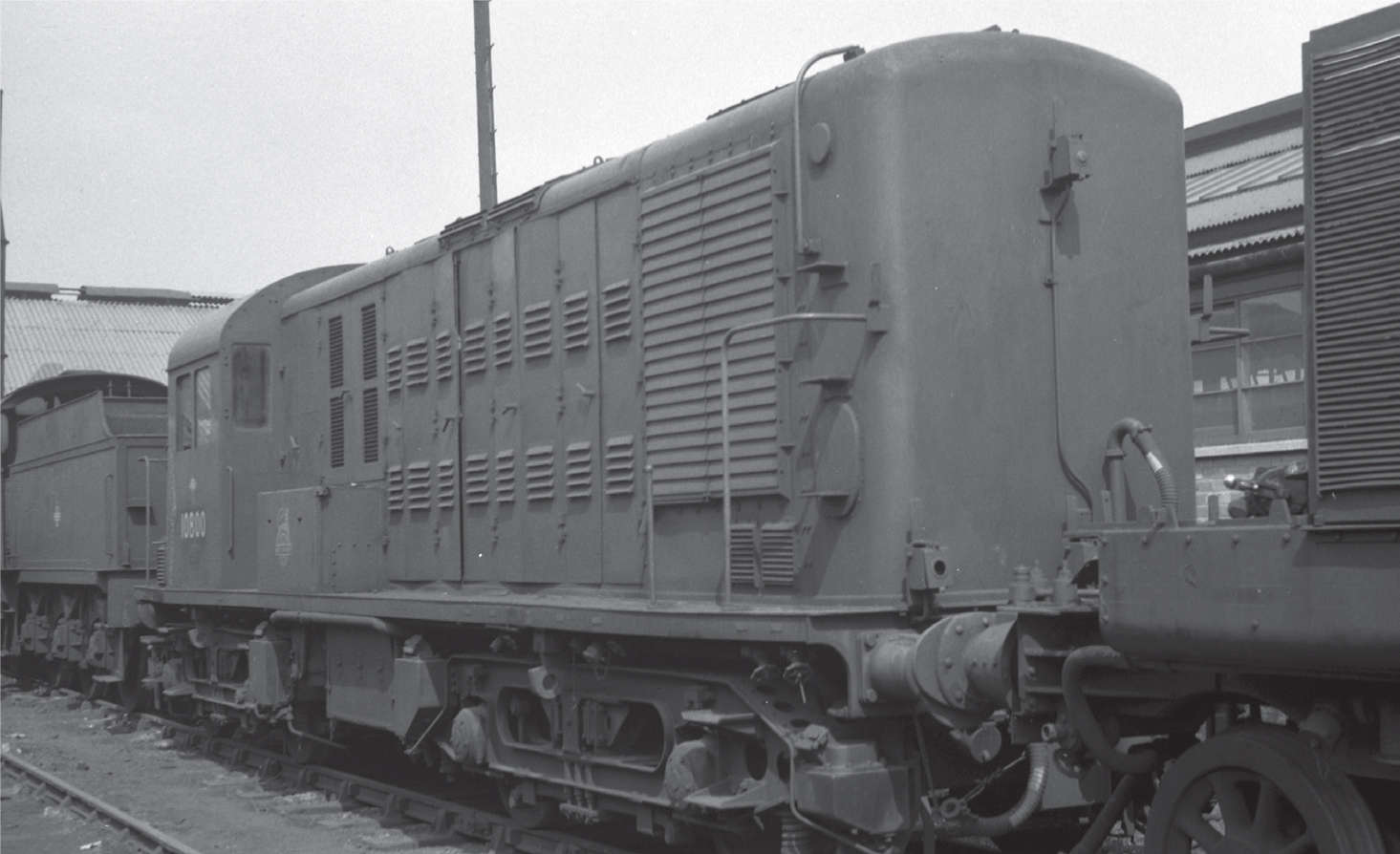

This Armstrong Whitworth 800hp diesel-electric locomotive was tested on the LNER in 1933. In a diesel-electric, the engine is connected to a generator that creates the power to drive the traction motors.

An LMS diesel shunter working at Toton marshalling yard in July 1939.

As it turned out, only no. 10000 a joint venture between the LMS and English Electric emerged before nationalisation in 1948. Though British Railways had taken delivery of six further locomotives by the mid-1950s, the tide didnt fully turn from traditional forms of motive power until recruitment problems combined with BRs financial difficulties to make it inevitable. A Modernisation Plan, published at the end of 1954, would see orders for 174 diesels placed from the following November. No one knew then that by 1968 many would be on borrowed time as the industry entered the Inter-City age and increasing competition from domestic airlines and road hauliers meant a growing need to fight for custom.

A portrait of the LMSs no. 10000, which featured a 1,600hp English Electric engine. It entered service in December 1947 the month before the LMS became part of British Railways.

PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE

A well-dressed man arrives at The Kremlin, his polished shoes tapping deftly on the pavement. Not that were in downtown Moscow, rather grey post-war London. Marylebone Road, to be precise

The building no. 222 got its nickname from its labyrinthine passageways and corridors. First a hotel, then a hostel for trainmen, its now the home of the Railway Executive (RE).

The GWRs experiments with gas turbine traction illustrated by no. 18000 indicate that the suitability of diesels for mainline use was not considered proven in the mid-1940s.

Ordered by the LMS, no. 10800 first appeared in 1950. Later rebuilt by Brush for testing purposes, it remained in active use until 1968.

The man Robert Arthur Riddles is the RE member for locomotive design and construction. Starting his career at Crewe Works in 1909, he went on to become Vice President of the London Midland & Scottish Railway. At the Ministry of Supply during the Second World War, hed been responsible for the acquisition of motive power. He owes his current position to one thing: nationalisation.

The war had moved many deceptively ordinary people to find the strength for bravery and selflessness, but it also led to a desire for social change that would see a landslide Labour victory in the 1945 general election. Once in office, the party made good on its pre-election promise to take public services into public ownership. As a result, the 1947 Transport Act saw the nationalisation of the Great Western, London Midland & Scottish, London & North Eastern and Southern railways (along with fifty smaller companies) from 1 January 1948.

The system was divided into six regions (the Eastern, London Midland, North Eastern, Scottish, Southern, and Western), above which sat the RE, which in turn answered to the British Transport Commission (BTC). The BTC had been established to provide an efficient, adequate, economical and properly integrated system of public inland transport and port facilities within Great Britain for passengers and goods. This meant that its first chairman, professional civil servant Sir Cyril Hurcomb, oversaw executives that controlled not only the railway, but also bus companies, road hauliers, docks, hotels, canals, tramways, shipping lines, London Transport, and even a film unit.

Built to the same design as no. 10000, no. 10001 appeared just after nationalisation.