Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor New York, NY 10018, USA.

E-mail:

www.shirebooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2016 James Taylor.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 832.

ISBN: 978-1-7844-2064-2 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-7844-2187-8 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-7844-2186-1 (eBook)

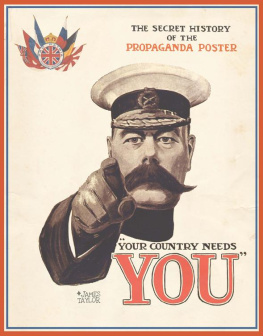

James Taylor has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

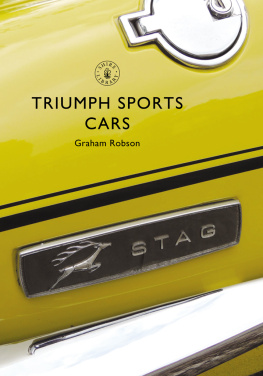

COVER IMAGE

A 1964 3.8 litre Jaguar Mk 2.

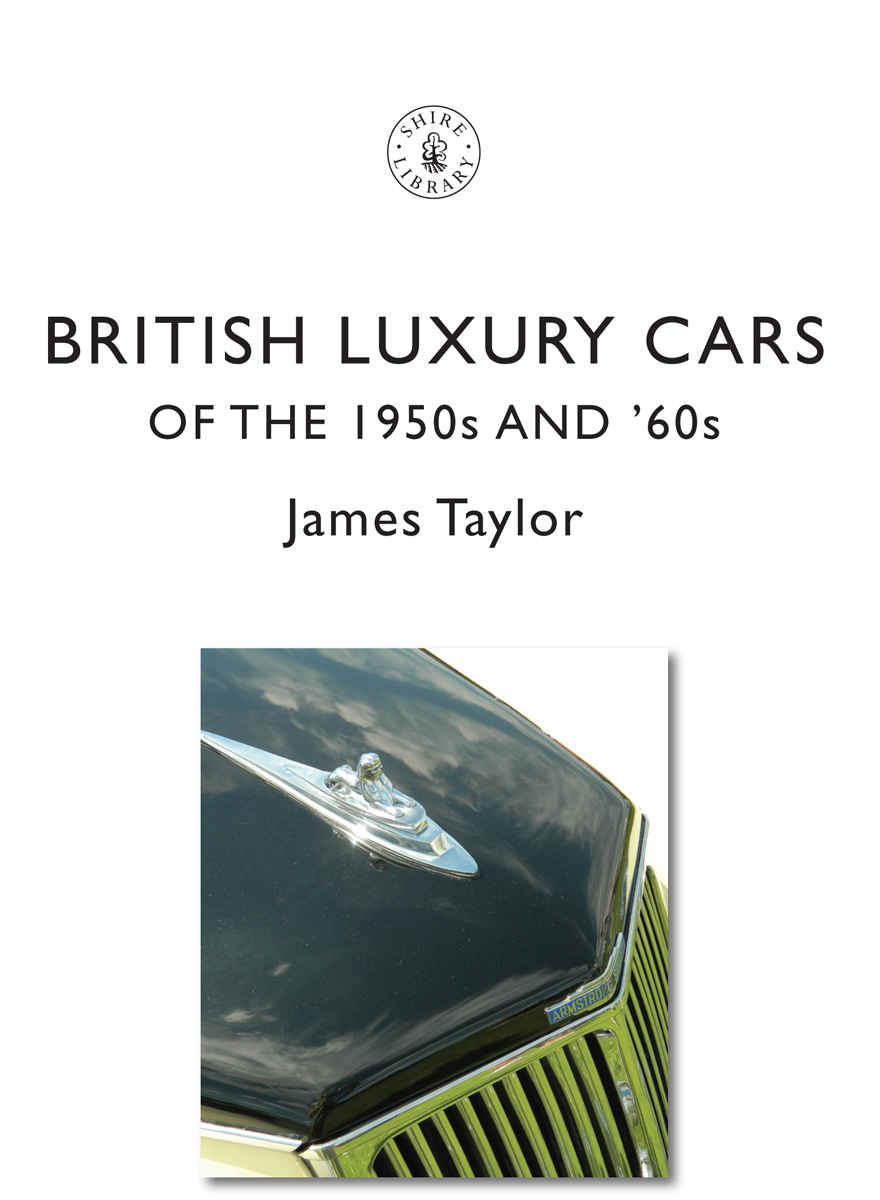

TITLE PAGE IMAGE

Many of the British luxury car makers went to the wall before the 1960s were out. This is the sphinx bonnet mascot of one of them, Armstrong-Siddeley.

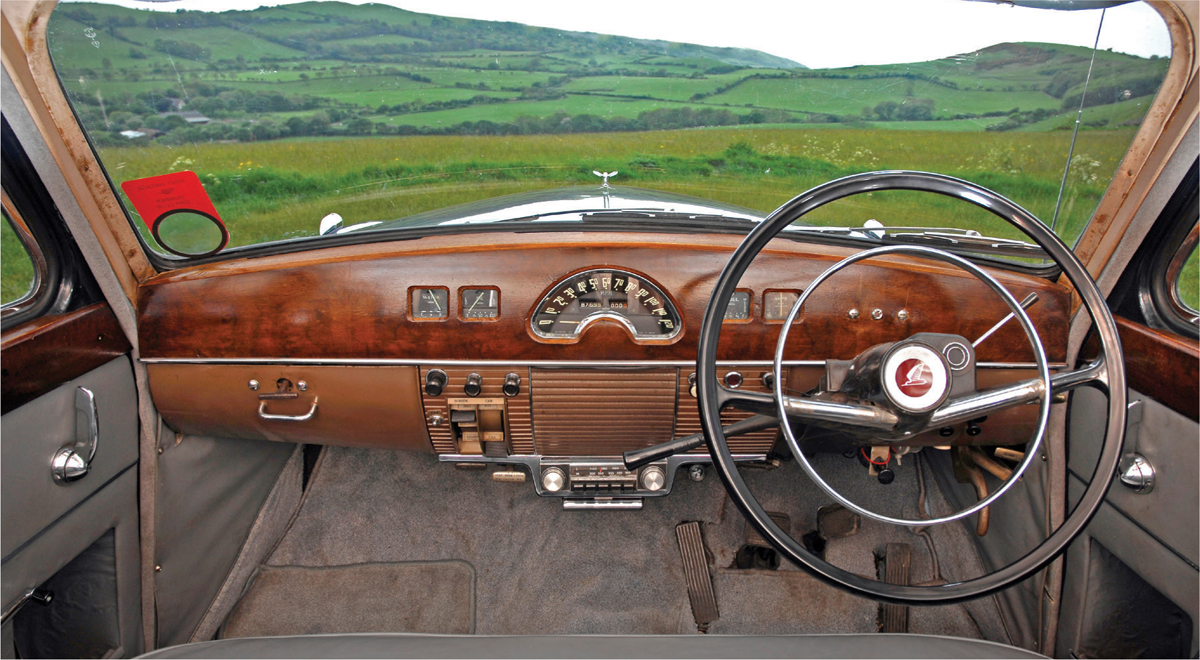

CONTENTS PAGE IMAGE

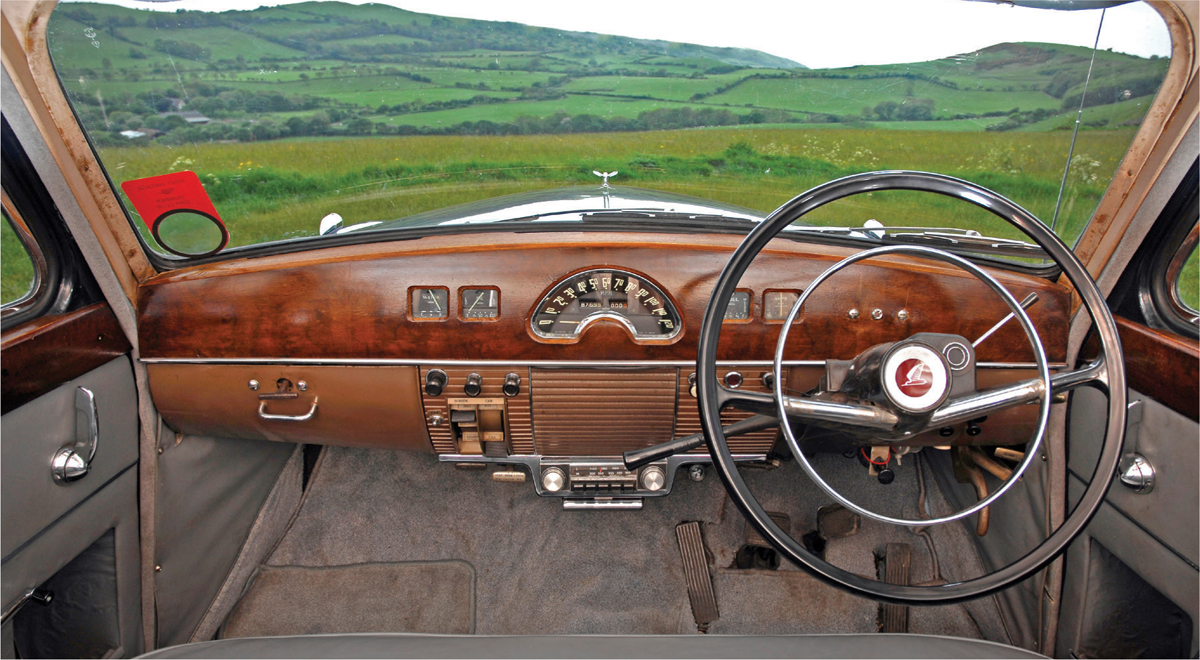

The Humbers dashboard blended transatlantic styling ideas with the traditional British reliance on wood.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Alamy, cover image; Charles01/Wikimedia, page .

CONTENTS

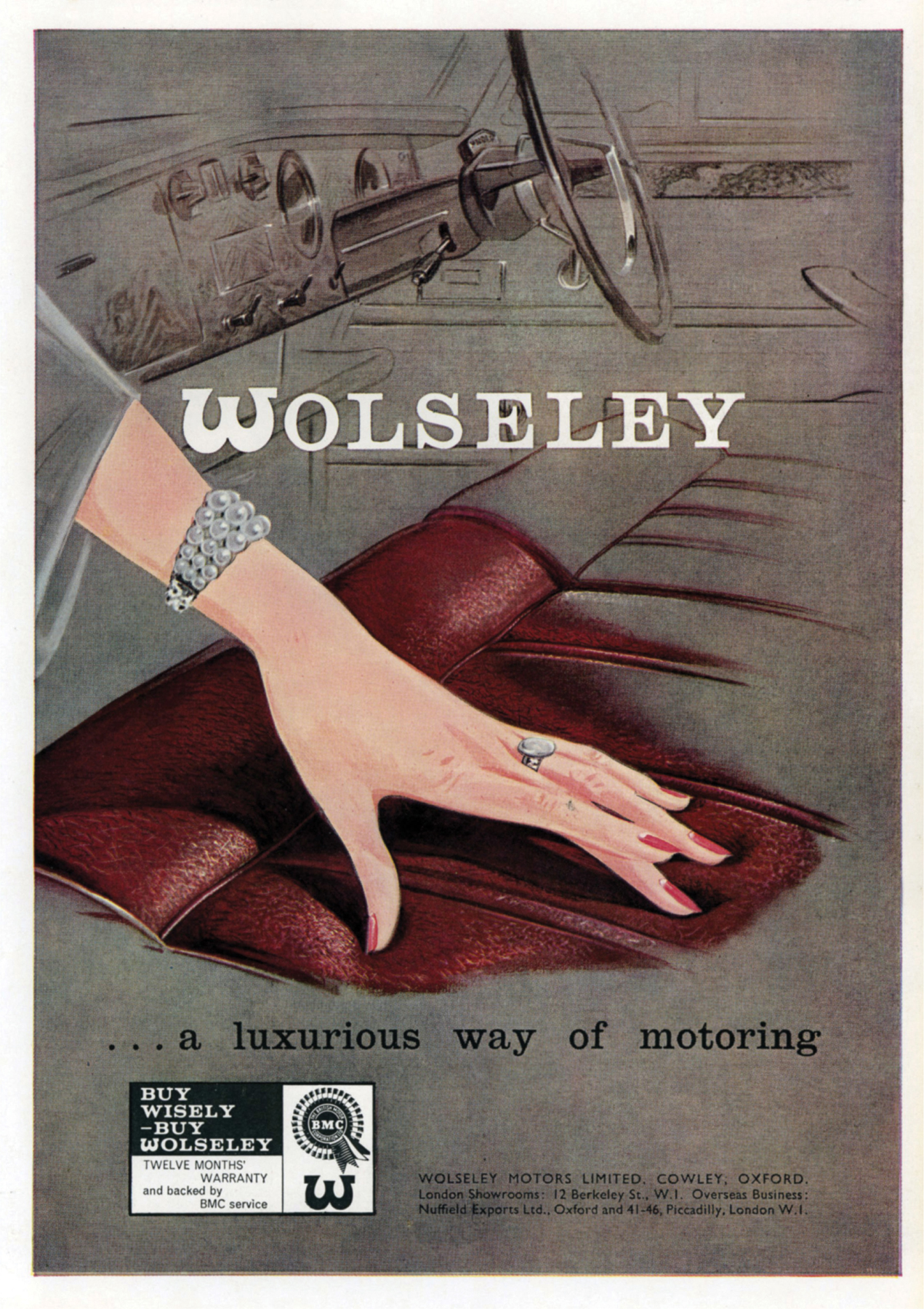

The cachet of leather upholstery was used to help sell a derivative of the big Austin, in this case badged as a Wolseley. The elegant female hand with its expensive jewellery is all part of the image.

INTRODUCTION

IN THE 1950s and 1960s, class distinctions were still very much part of the British national consciousness. Although the Second World War had gone a long way towards breaking down what remained of the old class structure after the Great War of 19141918, notions of them and us still shaped many aspects of British social behaviour. One of the aspects they affected was that of car ownership.

To some extent, it was a question of price: cost put most luxury cars beyond the reach of the average family. But, as is the case today, older luxury cars became more affordable when second-hand, and their buyers were able to enjoy their perceived superiority over more ordinary cars as well as benefit from their more luxurious specification. So demand for these cars remained strong after their first owners had moved on to something newer.

Right at the top of the car hierarchy were the twin marques of Rolls-Royce and Bentley. Traditionally, Rolls-Royce made The Best Car in the World, and few buyers knew or cared that this description was a trademark rather than an independent assessment. Rolls-Royce had asserted this position before the Great War and there was still no reason to believe otherwise. It was not until the early 1960s that Mercedes-Benz in particular made a determined attack on the Rolls-Royce market.

So, as the car maker at the top of the hierarchy although the small volumes it made meant it was far from the largest Rolls-Royce set the standard for others to follow. Despite changes made in the late 1940s to cope with a harsh economic climate, a Rolls-Royce was still a very superior kind of car, and its characteristics influenced the designs of other less expensive luxury saloons.

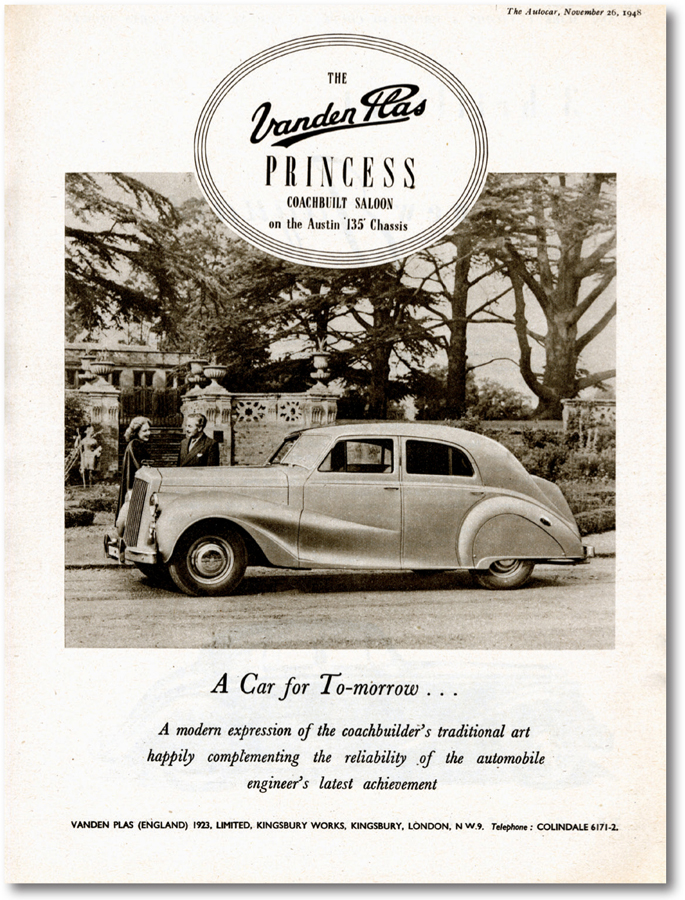

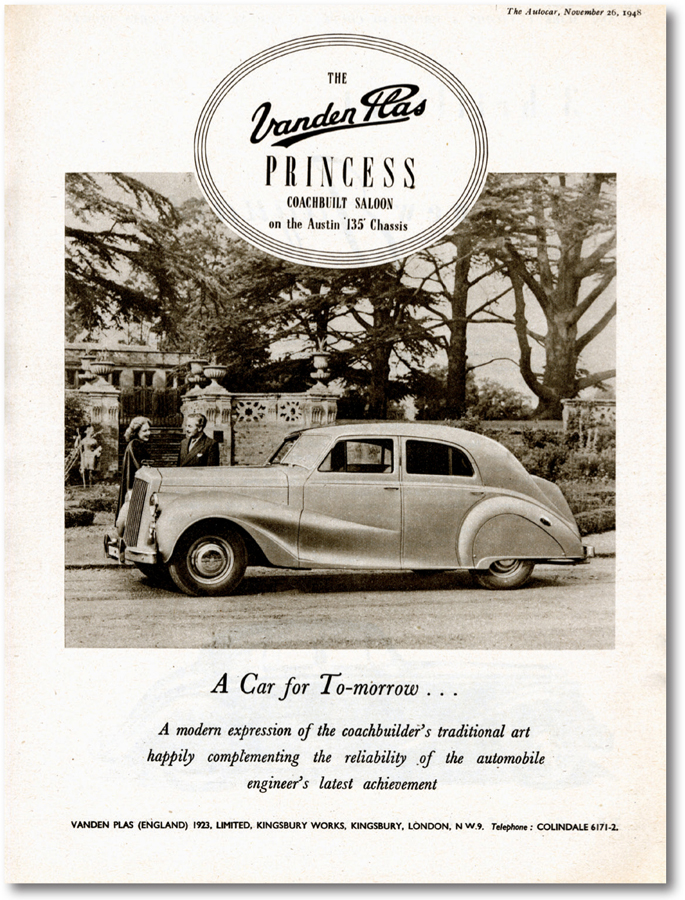

Vanden Plas had been a traditional coachbuilder before the Second World War. BMC bought it out in 1946 and used its name and expertise on luxury cars and limousines like this one. The basic design remained in production under different names for twenty years.

Britons at the start of the 1950s expected a luxury saloon to meet certain criteria: it needed to be large and impressive, and obviously superior to even the most expensive family saloons. It had to have a turn of performance that would leave ordinary family cars behind, although neither sporty handling nor exceptional speed were requirements. It needed spacious passenger accommodation with room for a division to be fitted behind the front seats so that rear-seat occupants could enjoy privacy while a chauffeur drove. A large luggage boot was also important.

Luxury cars were an important attribute of every VIP. Here, a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud collects Hollywood actress Joan Crawford in Johannesburg in 1957.

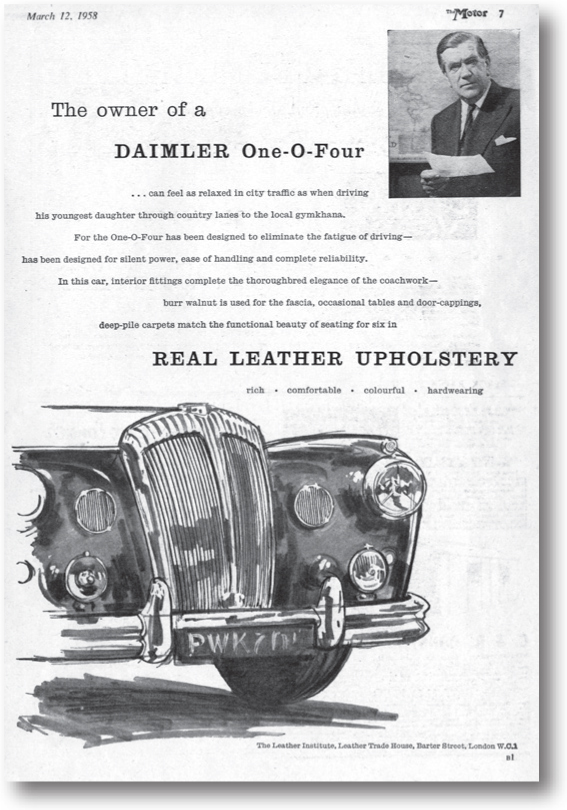

Upholstery had to be made of leather or, usually in limousines, the West of England woollen cloth that was less affected by extremes of temperature. When vinyl upholstery became more common in 1950s cars, it was deemed by many to be just that common and was not under any circumstances to be found on the seats of a luxury model. Top-end models often had leather or cloth on the door trim panels, although vinyl here was acceptable. Wood trim was an essential. At the very top of the market, carefully matched figured veneers and even inlaid wood finishes were expected, although by the end of the decade, there was acceptance for simpler and plainer wood finishes.

At a time when vinyl upholstery was becoming increasingly popular, leather took on its own cachet of exclusivity. This advertisement features the Daimler One-O-Four luxury saloon.

Luxury cars needed large and powerful engines to propel their bulk and weight at respectable speeds, and by the middle of the 1950s, it was widely accepted that anything smaller than 3 litres was insufficient because such engines generally lacked the necessary power and accelerative ability. The term 3-litre class came to define the luxury class, and both Rover (in 1958) and the British Motor Corporation (for their Vanden Plas model in 1959) chose the 3-litre name for their cars. It did not only define engine size; it also made clear that these cars were intended for customers of high social rank. The class distinction between these types of cars and more ordinary models was undisputed at the time, as was the distinction between the ordinary middle class and upper middle class, which it more or less paralleled.

The smoothness of a large-capacity, multi-cylinder engine was an important luxury car ingredient. This is the 3-litre six-cylinder in a Humber Super Snipe of the early 1960s.