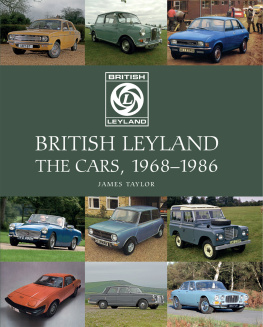

BRITISH LEYLAND

THE CARS, 19681986

BRITISH LEYLAND

THE CARS, 19681986

JAMES TAYLOR

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

James Taylor 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 392 9

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The story of British Leyland is a vast one, and already there have been many books and monographs that have tackled aspects of it. There are many different ways of looking at the story, but this book deliberately focuses on the cars and car-derived commercial products. The story of the companys evolution in the first section is designed to provide essential background to those products, and is not in any sense intended as an in-depth study of what is an enormously complicated piece of British social, economic and political history.

Surprisingly perhaps, defining exactly what was a British Leyland product and what was not is by no means straightforward. The approach taken here is a logical one, which separates the products into two groups: those that were inherited at the formation of BLMC in 1968, and those that were developed or reached the showrooms during the British Leyland era.

Inevitably these groups are complicated by the fact that some inherited products were further developed under British Leyland; the Mini, as an extreme example, was inherited, but survived right through the British Leyland era and beyond. The solution I have chosen is to discuss the further development of inherited models in the chapter devoted to them, but to treat any major change as the creation of a new model, therefore including it in the British Leyland chapter. So, to follow the example of the Mini, the story of the inherited Mk II models is in the earlier chapter, but from the point where they became Mk III models with Leyland badges, they are in the later chapter.

As for a cut-off point, I have chosen 1986 because this was the year that the old British Leyland ceased to exist, and what was left of the car and light commercial business was renamed the Rover Group. Inevitably, some new models appeared right on the cusp of the changeover a notable example being the Rover 800. However, even though these were developed under British Leyland, they were not sold during that companys lifetime and are therefore not included in this book.

Vitally important in the British Leyland story is the question of exports. Listing all the countries to which each individual model was exported would be tedious and probably not very enlightening. So would the full story of all the overseas assembly plants that built BL models from CKD. However, where overseas plants developed distinctively different models, I have guessed that their story might be of more interest, and so have included these in a further chapter.

Next, British Leyland used an enormous and potentially confusing variety of engines in its car and car-derived commercial ranges in this period. To avoid complicating the main text, and to avoid a degree of repetition, I have put the details of all these engines in an Appendix. Finally, British Leyland inherited a large number of factories, and another Appendix provides a ready reference to these.

Throughout this book, every effort has been made to ensure technical accuracy. I have drawn on a large number of sources for the information in it, and I have also tapped into the knowledge and the memories of a very large number of people. To all those who contributed their thoughts and ideas, here is my chance to say thank you, and to apologise if I have misunderstood what you tried to tell me.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire, 2017

1 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH LEYLAND

T HE STORY OF BRITISH LEYLAND is an enormously complicated one, and the purpose of this section is simply to provide a framework to act as background to the story of the cars it produced. Indeed, it is sometimes difficult to determine exactly when British Leyland began and when it ended; the dates chosen for this book are 1968, when the British Leyland Motor Corporation was formed, and 1986, when what was left of that grouping was formally renamed as the Rover Group.

One other point needs to be made at the start. British Leyland was a vast organization, with manufacturing interests in many areas beyond cars and light commercial vehicles. This book makes no attempt to deal with these other interests: it is purely about those cars and the light commercials that were directly derived from them.

The British Leyland Motor Corporation, 1968

BLMC formally came into being on 17 January 1968, and was the result of a merger between British Motor Holdings (BMH) and the Leyland Motor Corporation. BMH was then the largest car manufacturer in Britain, nearly twice the size of the Leyland group. It had been formed as BMC (British Motor Corporation) in 1952 by the merger of Austin and the Nuffield Organisation. In 1966 it had become BMH, when Jaguar and its Daimler subsidiary joined the fold. Leyland, meanwhile, was a long-established truck and bus manufacturer that had branched out into car manufacture by taking over Standard-Triumph in 1961.

The 1968 merger was brokered by the Industrial Reorganization Committee, which was then run by Tony Benn. It was an organization established by the Labour Government under Harold Wilson to create a more efficient British industrial base through mergers and reorganization. While the Leyland group was in a strong position, BMH was getting dangerously close to collapse, partly because many of its models were outdated.

Benn was particularly concerned that Britain had no motor industry group big enough and strong enough to counter the major groups in Europe, particularly Volkswagen. He believed that merging the two British groups would produce a group large enough to achieve this, and would also save BMH from collapse. Over the summer of 1967, he encouraged talks between the top management of both sides, and agreement was reached.

Next page