FURTHER READING

Anderson, Curtis Darrel, and Anderson, Judy. Electric and Hybrid Cars: A History. McFarland, 2005.

Kirsch, David A. The Electric Vehicle and the Burden of History. Rutgers Universi ty Press, 2000.

Larminie, James, and Lowry, John. Electric Vehicle Technology Explained. John Wiley & Sons, second edition, 2012.

PLACES TO VISIT

In addition to the permanent exhibitions listed here, many motor and other museums hold special electric-vehicle exhibitions fro m time to time.

Grampian Transport Museum, Alford, Aberdeenshire, AB88 8AE. Telephone: 01975 562292. Website: www.gtm.org.uk The museum has a replica of the electric powertrain made by local inventor Robert Da vidson in 1839.

Route 66 Electric Vehicle Museum, 120 W, Andy Devine Ave, Kingman, AZ 86401, USA. Website: www.hevf.org This is the worlds only specialist museum for ele ctric vehicles.

Transport MuseumWythall, Chapel Lane, Wythall, Worcestershire, B47 6JA. Telephone: 01564 826471. Website: www.wythall.org.uk This museum has an important collection of battery-electric light commercial vehicles, built between the 1930s and t he early 1980s.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Alexander Migl/.

Page numbers refer to the print edition.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

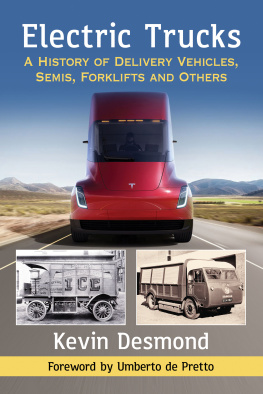

James Taylor has been writing about cars and transport since the 1970s and his books for Shire include Family Cars of the 1970s, British Sports Cars of the 1950s and 60s, Land Rover and Vauxhall Cars.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Kemp House, Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9PH, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

www.shirebooks.co.uk

SHIRE is a trademark of Osprey Publishing Ltd

First published in Great Britain in 2022

This electronic edition published in 2022 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

James Taylor, 2022

James Taylor has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on p. 63 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978 1 78442 491 6

eBook ISBN: 978 1 78442 492 3

ePDF ISBN: 978 1 78442 494 7

XML ISBN: 978 1 78442 493 0

Shire Publications supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity.

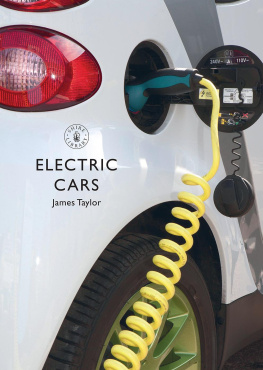

Front cover: An Electric Smart car on charge (Alamy). Back cover: The British road sign indicating a charging point (Crown Copyright/Open Government Licence).

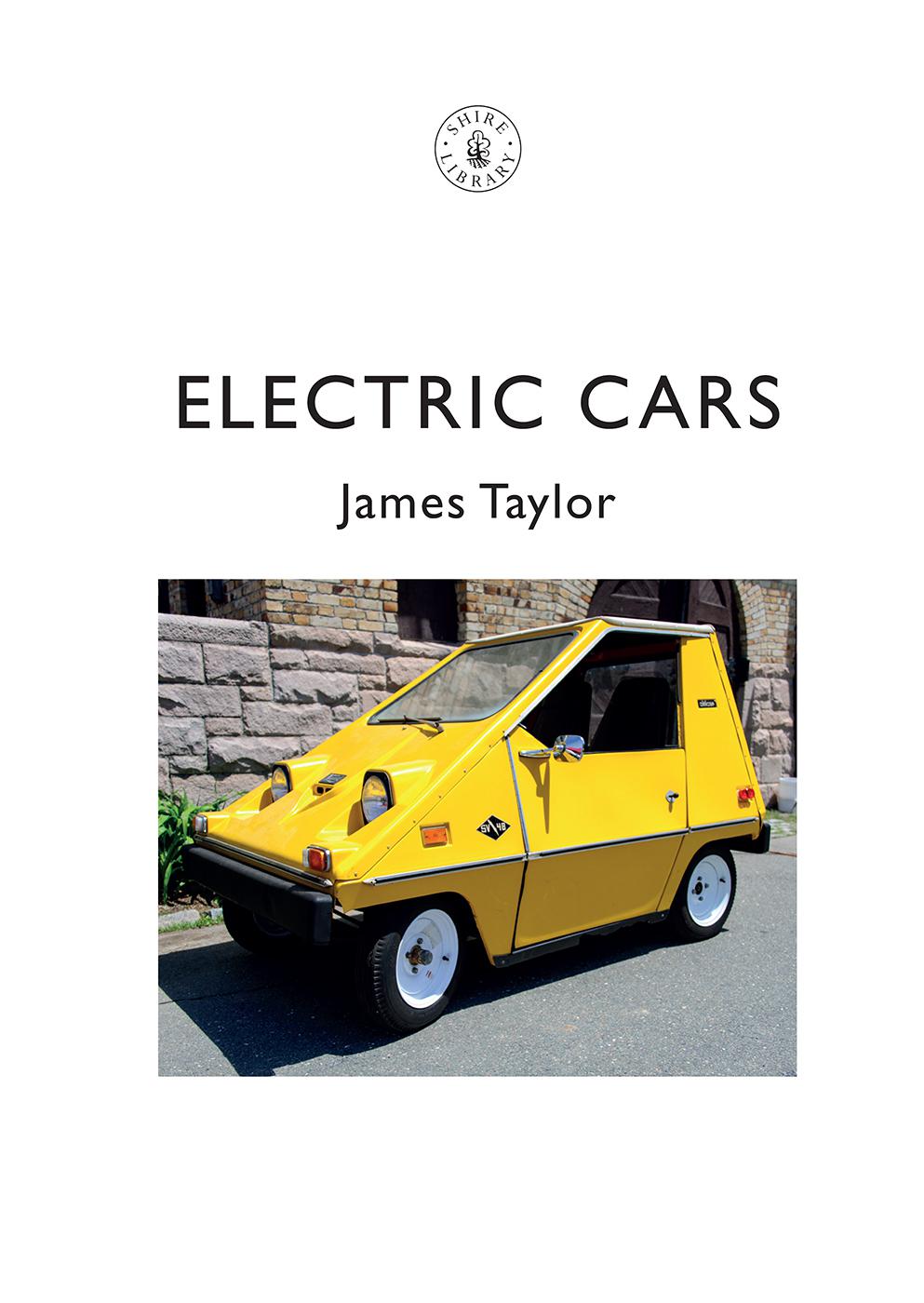

The CitiCar was designed and produced in Florida from 1974 to 1977. (Eric Kilby/CC-BY-SA-2.0)

The dashboard ot the 2020 Honda E Advance, which deliberately tackled the urban runabout market, offering a range of just 125 miles but driving dynamics that tempted the driver to use it for longer runs. (Honda Wales/CC-BY-SA-4.0)

EARLY DAYS

A t a time when electric or hybrid electric cars appear to provide the future of personal road transport, it is no surprise to find car manufacturers dredging up claims to early experiments with battery propulsion. In fact, the earliest experiments with battery-powered cars pre-dated the founding of any of todays car manufacturers. They were, however, ju st experiments.

The defining feature of an electric car is its use of electricity to power the wheels that provide motion. That electricity must be stored on board the vehicle, and as a result, electric cars are and always have been entirely dependent on the storage capacity of their batteries and on the ability of these batteries t o be recharged.

The first true battery was invented by Alessandro Volta in 1800, but it suffered from numerous problems and was impractical except as an experimental tool. The technique of storing electricity in a battery was gradually developed by several inventors over the next half century, but the batteries of the period could be used only once: their usefulness ended when the chemical reactions that created electric ity were spent.

None of that prevented inventors from seizing on this new source of portable power and designing battery-powered vehicles in the first half of the nineteenth century. Working independently of one another, individuals in Hungary (1828), the Netherlands (1835), the USA (1835), and Scotland (1839) came up with experimental vehicles, but the details and precise dates of some of these inventions are obscure. As demonstrations of theory, they were a start, but they were not by any means practical passenger-car rying vehicles.

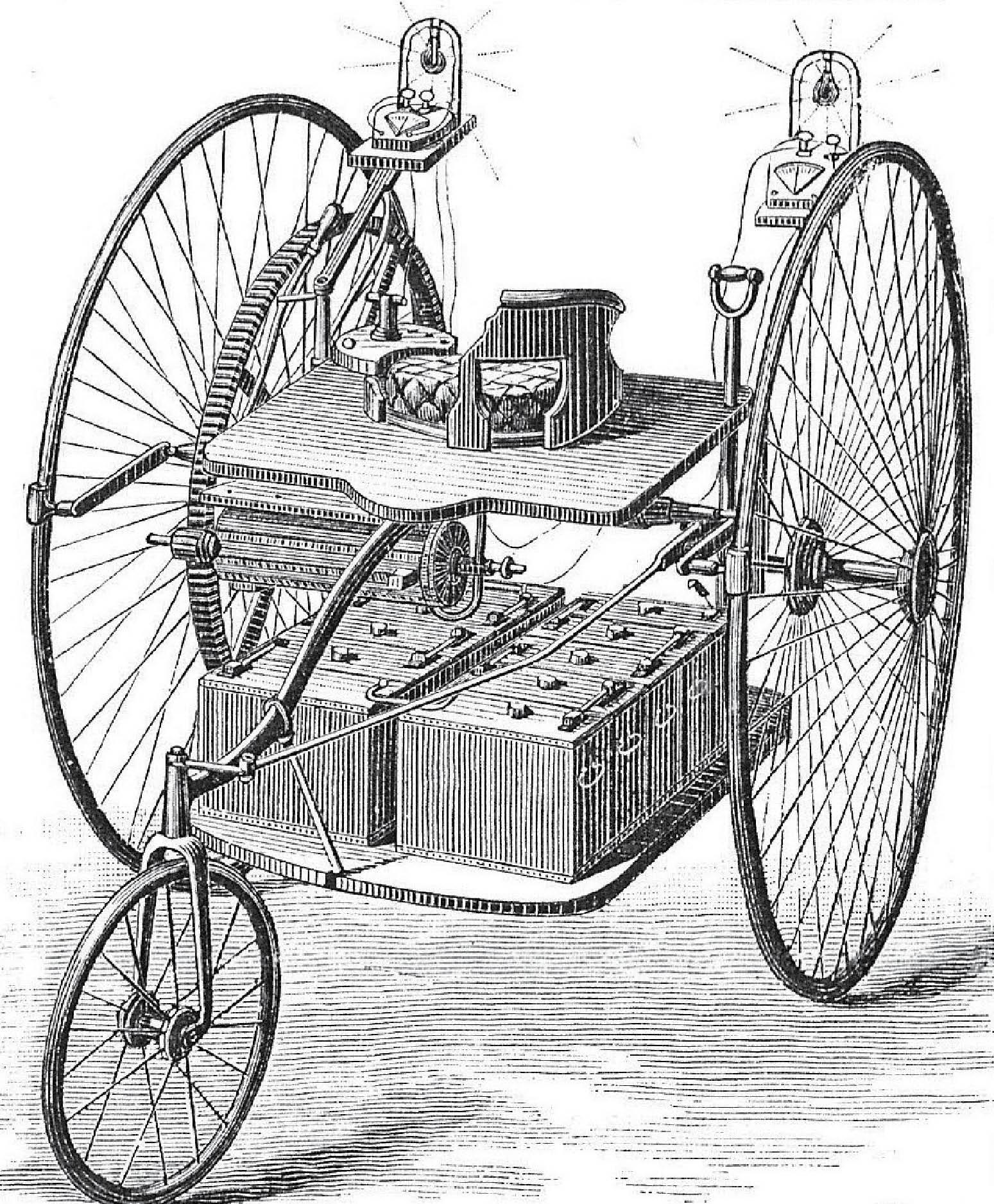

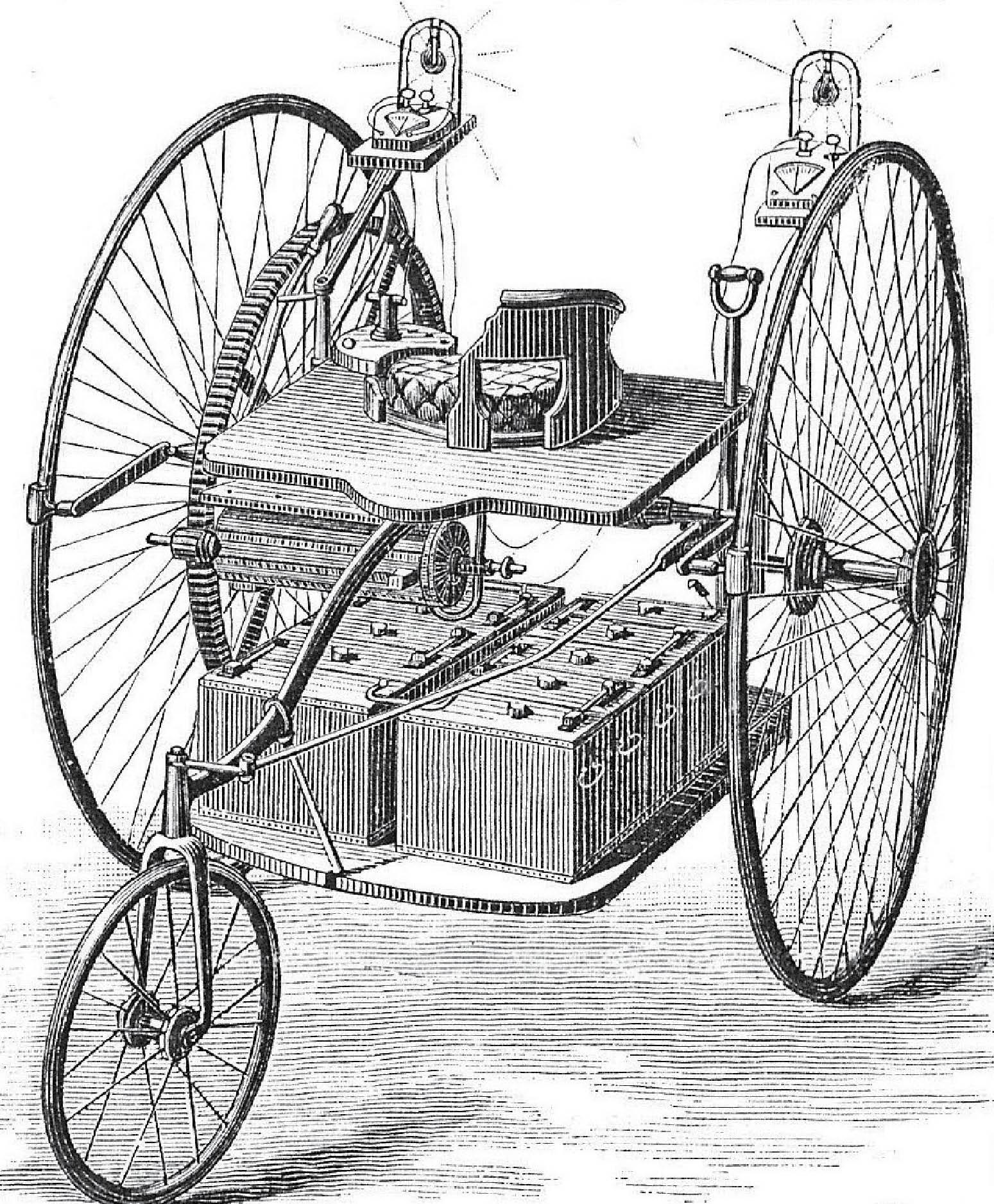

Gustave Trouv added batteries and an electric motor to a British-made tricycle in 1881.

The invention of the leadacid battery by the French physicist Gaston Plant in 1859 brought a key advance in battery technology: it could be recharged by passing a reverse current through it. However, even then it would be some years before such batteries would become readily available. It was only after some major improvements to the design of the leadacid battery by another French scientist, Camille Alphonse Faur, that mass production of batteries was made feasible.

A number of experiments with battery-powered road vehicles followed in Europe. Quickest off the mark was the French inventor Gustave Trouv, who adapted a German Siemens electric motor to power a British-made Starley tricycle, and tested it on a Paris street in April 1881. Developing his ideas further, he presented an electric car at the Exposition internationale dlectricit in Paris that November. This unfortunately proved to be a dead end as he was unable to patent his ideas, so he turned his attention towards electricity for marine prop ulsion instead.

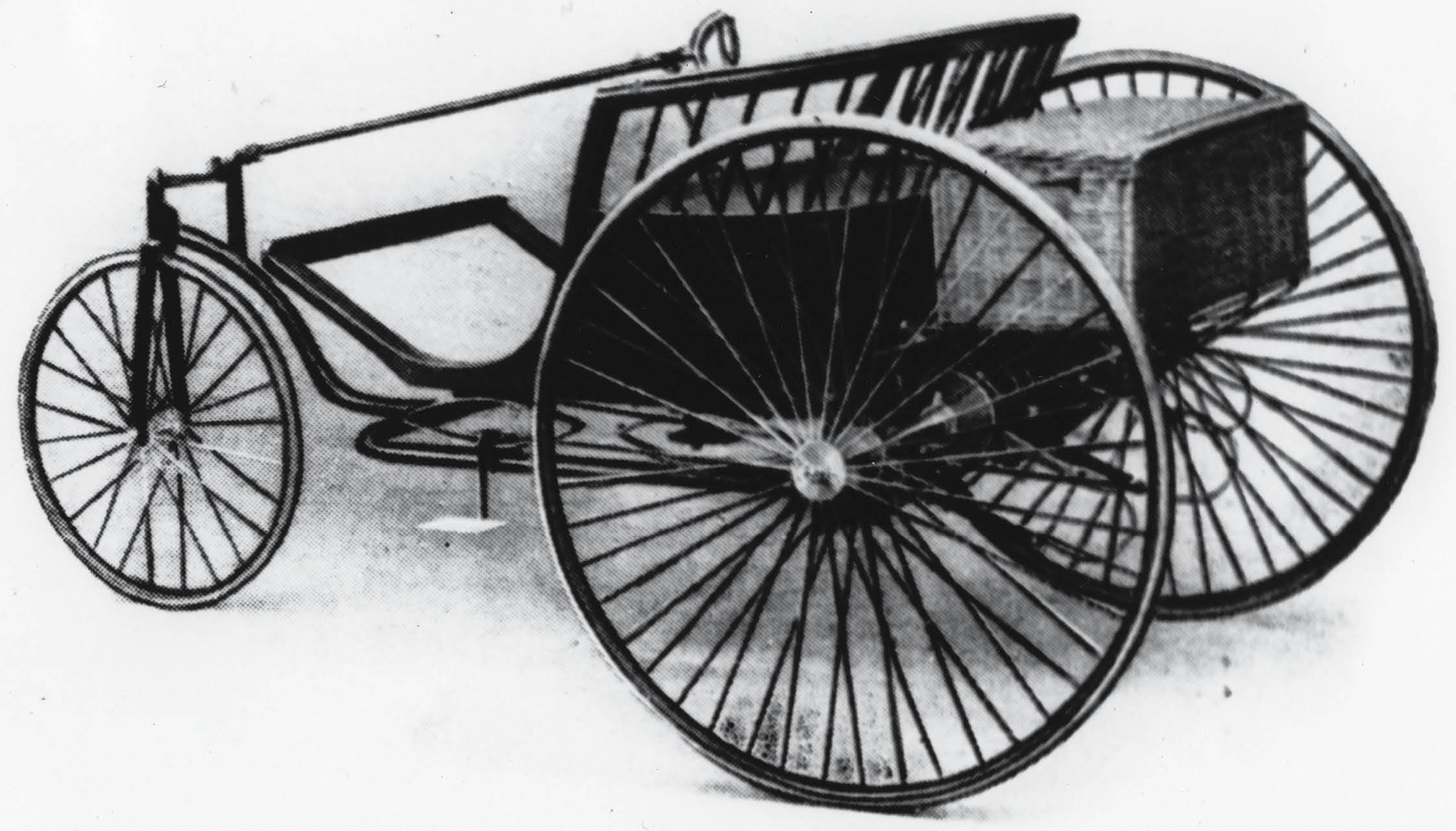

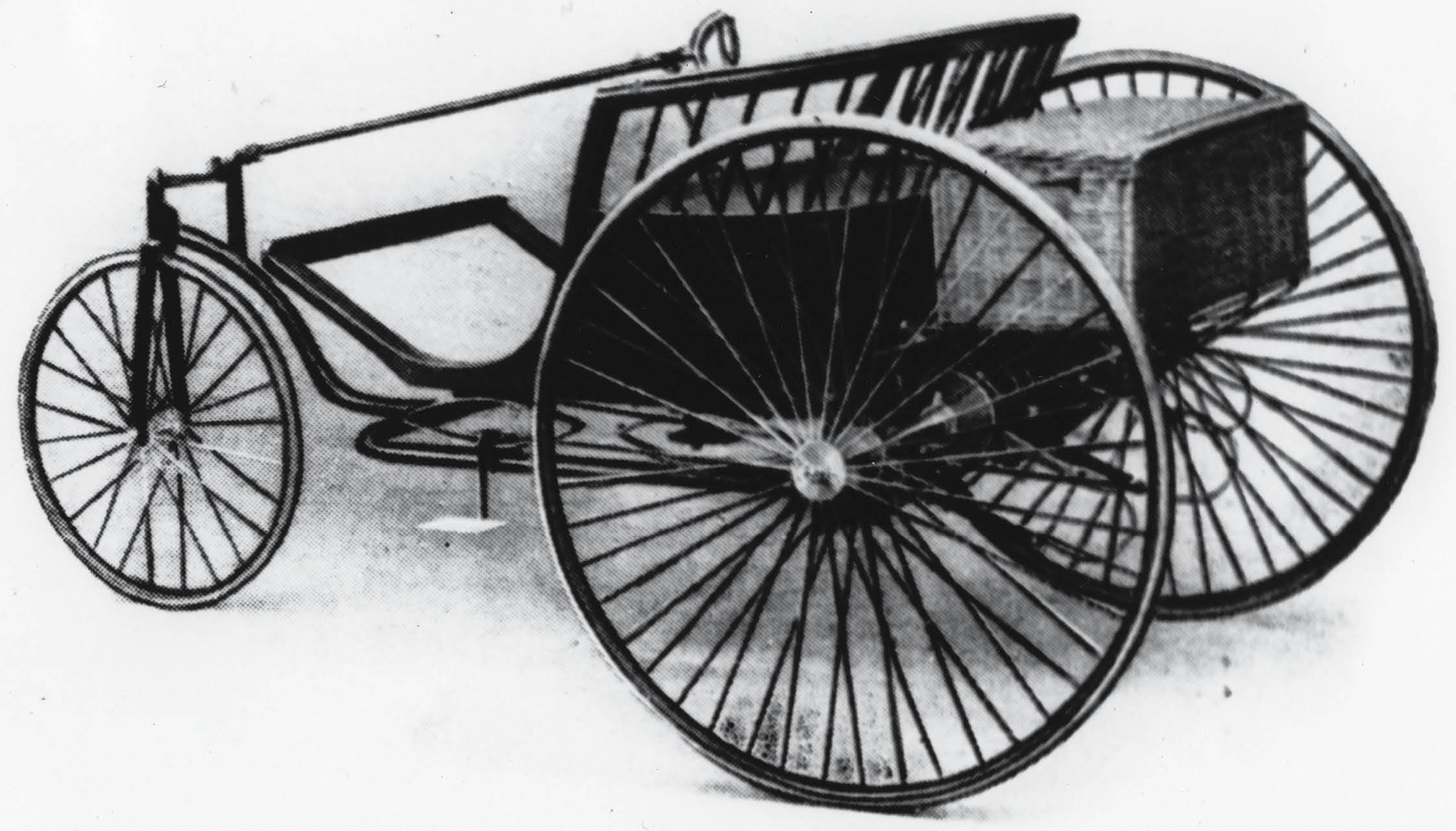

In 1887, JK Starley in Britain built an electric version of his companys tricycle the latest version of the model that Gustave Trouv had electrified six years earlier.

Not long afterwards, the British inventor Thomas Parker began to look at the viability of an electric-powered car for his company, Elwell-Parker of Wolverhampton, which was established in 1882 as a maker of accumulators and would later be responsible for major urban electrification projects such as the London Underground and the tram systems in Birmingham and Liverpool. Parker had an experimental electric car running by 1884, and his experiments continued after the company became part of the Electric Construction Corporation in 1889. Notable among them was an electric dog cart that was built in 1896. Meanwhile, in Germany, the inventor Andreas Flocken produced his idea of an electr ic car in 1888.

Next page

Next page