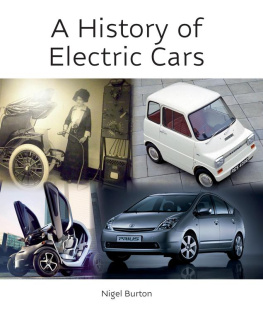

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the car industry was in its nascent period. Cars were beginning to take over from the horse and carriage, but only the wealthy could afford to buy one. All over the world, hundreds of former carriage companies had diversified into building automobiles. Three propulsion technologies were competing for the emergent market, but only one appeared to have a winning hand: it offered pioneering motorists the quietest and smoothest drive; it powered cars to the land-speed record; it was easy to start and the cars that used it were so simple to drive almost anyone could get to grips with it in a few hours; whats more, the fuel it used was both cheap and widely available throughout the developed world. Yet, despite these apparently crushing advantages, the electric car failed to capture the buying publics imagination. Its failure left drivers with only one choice: the internal combustion engine. Indeed, so thoroughly was it routed, that the role electric vehicles played in the early development of the automobile has been largely expunged from history. Only a few grainy black-and -white photos remain of cars that, once upon a time, ruled the roads.

Fast-forward 100 years and the electric car is once again in the ascendency. Vehicles such as the Toyota Prius, the Nissan Leaf and the Chevrolet Volt are in the vanguard of a new generation of cars that use battery power. Some, like the Prius and the Volt, use electricity to reduce running costs; others, like the Leaf, to slash exhaust pollution, and a select few, like the Porsche 918, harness electric motors to boost their outright performance.

The Porsche 918: state-of-the-art application of petrolelectric hybrid technology promises supercar performance with the running costs of a large family saloon. But this isnt the first highperformance Porsche hybrid.

Car manufacturers have turned to electricity over fears of a looming environmental disaster. As Carlos Ghosn, chairman and chief executive of the Renault Group, says:

The Renault-Nissan alliance is targeting sales of 1.5m zero emissions vehicles by 2016, delivering a 20 per cent reduction in our carbon footprint and a 35 per cent improvement in our overall fuel economy. Beyond pure sales volumes the LEAF symbolises our wide-angled view of society. The world already has seven billion people and one billion cars. The Nissan LEAF shows that the automobile industry can contribute to sustainability without giving up our role as a source of unmitigated excitement and mobility. The electric car will represent a very big percentage of our industry in the future.

Global warming has brought the electric car and its close cousin, the hybrid back from obscurity. However, the obstacles to sales success these new vehicles face are just the same as they have ever been. If the electric car is to accomplish in the twenty-first century what its predecessors so spectacularly failed to achieve a century ago, manufacturers must learn the lessons of the past.

Why did electric cars fail to catch on in the first years of the twentieth century, despite their early advantage? And how did the development of electric vehicles proceed so much faster than the competing technologies of internal combustion and steam power, only to come to a complete halt?

The early years of the electric car are filled with stories of snake oil salesmen, dubious speculators and patent trolls. Many of the outrageous claims made for horseless carriages were untrue. Motorists who found themselves stranded miles from anywhere with a flat battery had good reason to be angry when their car failed to achieve the range-to-empty figures they had been promised. Henry Ford, whose wife used an electric car, was so alarmed by the poor dependability of batteries that he even built a charging station just so he could be sure his wife would always be able to get home.

But, for all their drawbacks, electric cars did have many good points. Had the electric car industry found its own Henry Ford (and it almost persuaded Ford himself to be its advocate, see ), history may have been very different.

And it all began with the battery a ground-breaking discovery, which came about as a result of a friendly dispute over frogs legs.

Alessandro Volta: Italian physicist who invented the first battery capable of supplying a reliable electric charge.

Although some historians believe the electrochemical cell was invented in Mesopotamia shortly after the crucifixion of Christ, the man most widely credited with the discovery of the modern-day battery was the Italian chemist and inventor Alessandro Volta.

Volta was born in Como, Italy, and was a physics professor at the citys Royal School. In 1775, he took an invention by a Swedish professor called Johan Carl Wilcke and refined it to create what he dubbed the electrophorus. The device consisted of a dielectric plate made from resinous material and a metal plate with an insulated handle. When the dielectric plate was charged, by rubbing it with fur or cloth, the resulting electrostatic induction process created a charge in the metal plate, which could be used for experiments.