First published 2017

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright William Wright, 2017

The right of William Wright to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 9781445665481 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445665498 (eBOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

CONTENTS

MAPS

PREFACE

In the three months between late August and late November 1879 the two most warlike and dangerous potentates in southern Africa were captured, their kingdoms destroyed, the military prowess of their armies and states blown to the winds.

One man was responsible for this, one Englishman tasked with restoring national honour after a string of costly and humiliating defeats, mistakes and fiascos. His name was Garnet Wolseley. He is largely forgotten today despite a statue on Horse Guards Parade and a tomb in St Pauls Cathedral. Yet the mid-Victorians thought him the master of irregular colonial warfare, so much so that he was satirised on the stage by Gilbert and Sullivan as the very model of a modern major-general. His skills as a soldier and ability, as Disraeli said, to not only succeed but succeed quickly helped create a new term in the English language, All Sir Garnet, meaning ready and in apple-pie order.

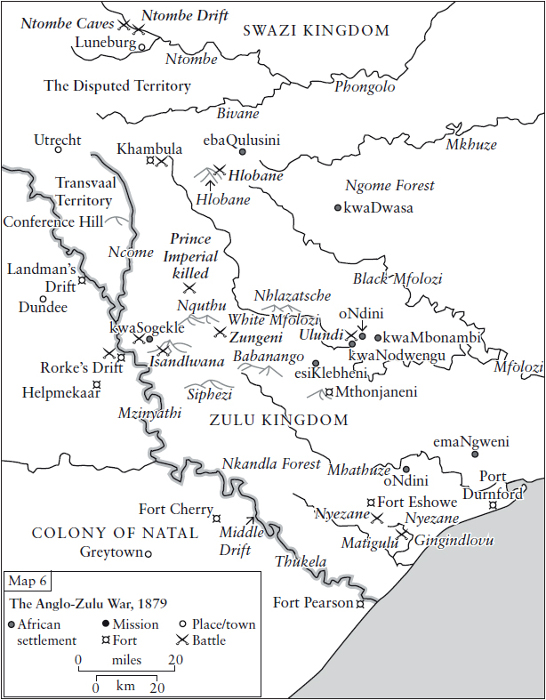

In May 1879, after a series of disasters in a war against the Zulu kingdom that was forced on the British government, a conflict planned without prior knowledge in London by the countrys man-on-the-spot, Sir Bartle Frere (in concert with his military commander, General Lord Chelmsford), the Prime Minister finally thought enough was enough. He sent out Wolseley with wide powers to end the war, capture the Zulu king, settle the country and do it all cheaply and without annexation.

Before Sir Garnet could take charge Lord Chelmsford managed to bring the Zulus to battle near the royal kraal, thus saving his reputation and ending the war. Most books on the events of 1879 end with this, the Battle of Ulundi. The whole affair was over or was it?

This book examines 1879 through the eyes of Wolseley, using his personal journal and hundreds of his letters. My special focus is that period after Ulundi. This began with an eight-week-long king hunt as Cetshwayo was pursued across Zululand. Much to their credit, his people refused to give him up. Desultory fighting continued and the last British soldier did not die in action until sixty-five days after the Ulundi battle.

Wolseley then carried out a reorganisation of Zululand. This rushed settlement has been decried ever since. It was controversial at the time and still remains so. Failings in the scheme were one cause of a disastrous civil war that rocked Zululand a few years later. It is impossible to defend the indefensible, but I have tried to examine every document of Wolseleys I could find, to see what was in his mind when he made his plans. Who really guided him? What did he hope to achieve for the Zulu people? Were his aims Machiavellian or benign?

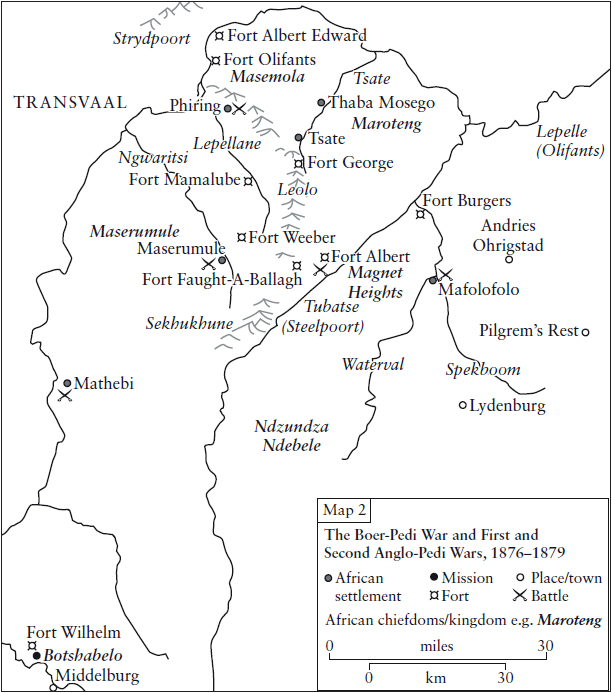

After Zululand Sir Garnet set off for the newly acquired British territory of the Transvaal, where he hoped to deal with some rumblings of Boer discontent and return home by Christmas. Trouble was unfortunately looming, with the powerful Bapedi tribe in the eastern Transvaal under a remarkably cunning leader called Sekhukhune. From their extraordinary mountain fastnesses the Bapedi had seen off Swazi and Zulu invaders as well as two white armies, one of them British. A chain of events now led Wolseley into a war he did not want. It ended on 28 November 1879 in a long and bloody battle, the only offensive one waged by the British in that years long succession of military encounters. Some defenders then hid on a last redoubt called the Fighting Kopje and took four more days to surrender.

This book presents what I think is the fullest account so far published of the Second Anglo-Pedi War. I have also toured the battlefield, tucked away in a remote corner of South Africa.

The book introduces a large and colourful cast of characters British, Boer, Pedi and Zulu. I have tried to tell their story in a narrative style and to let the original participants speak for themselves where possible. Any lapses in style or mistakes in Bapedi or Zulu terminology, or choice of spellings (is it Sekhukhune, Sekukuni, Secocoeni and so on) are down to me and I apologise if I have introduced any errors. My sources are listed at the end of the book. I also undertook two field trips to South Africa. I hope the reader thinks the efforts worthwhile.

General Wolseley was a prolific correspondent; he wrote numerous letters daily to public and private figures, not to mention his large family and especially his wife. In Zululand he also kept a daily journal to put down his thoughts. This is in the National Archives but was published with scholarly notes in South Africa in 1979. The book is now out of print and a rare find. I have used the journal as a template to expand on our knowledge of Wolseleys actions. Along the way I have read over 600 of his letters in British and overseas institutions. The generals letters to his wife are particularly revealing and sometimes quite shocking.

Two theses were of especial help in steering a path on Transvaal affairs: Kenneth Smiths pioneering study of the BapediBoer War of 1876 and the British ones of 187879, and Bridget Theron-Bushells in-depth examination of Owen Lanyons time as an administrator in South Africa. Very recently the doyen of South African military historians, John Laband, has written some chapters on the Bapedi campaigns that were also most useful. Any person researching this period owes a special debt to these historians.

Among those persons holding copyright I must first thank HM the Queen for permission to quote from the letters of HRH the Duke of Cambridge, Queen Victorias cousin. At Hove the library team were helpful as ever, and Mark Bunt was a godsend in preparing in advance all the Wolseley letters I needed to see. He even dragged down some scrapbooks from the attic. My time at Hove was wet and windy as only an English seaside town can be when out of season. My thanks to Mary Nimmo for giving me a slap-up breakfast every day before I trudged off into the storms.

In South Africa the staff at the Campbell Collections (formerly the Killie Campbell Africana Library) in Durban, the kwaZulu Natal Records Office in Pietermaritzburg and the National Archives in Pretoria all gave up their time for my odd enquiries. The director of the Lydenburg Museum was friendly to a stranger calling without an appointment, while my hosts even offered to put me in touch with the Bapedi paramount chief. A final thank you to my guide at Tsate in South Africa, whose name I have sadly misplaced, but who will never be forgotten.