My thanks again to Elizabeth Bodill for the patience in coping with many revisions of this book. My thanks are also due to Miriam Vigar for reading the draft manuscript and contributing constructive suggestions; to Peter Quantrill, my co-author on other projects, for valued observations; to Michael Leventhal of Frontline Books for his continual interest and encouragement; John Young for his generosity in supplying the jacket illustration; the staff of the Killie Campbell Library (now called The Campbell Collection); and likewise the Africana Museum, Johannesburg; to Arthur Konigkramer of AMAFA and, last but not least, my graciously long-suffering wife in the midst of rooms strewn with books and papers whilst moving house.

Chapter 1

First Come the Traders

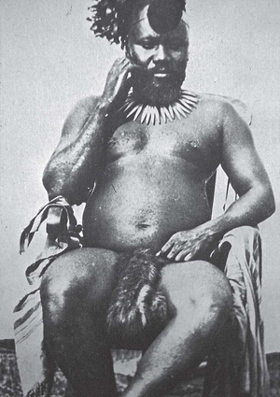

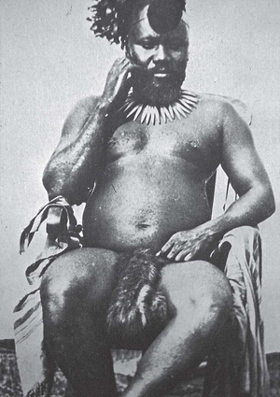

First came the trader, then the missionary, then the red soldier. Such was the remark attributed to Cetshwayo kaMpande, king of the Zulu nation, as he attempted to grasp the implications of an ultimatum that the British High Commissioner for southern Africa had served upon him in December 1878. It was an ultimatum so outrageous in what it demanded, that it was quite clear it had been designed to be totally beyond the compliance of the Zulu king. Now there would be war: Cetshwayos army, medieval in terms of weapons, versus the red soldiers of Queen Victoria, armed with the breech-loading rifle.

Although the Zulu, who call themselves the People of Heaven, had held sway in south-eastern Africa ever since King Shaka had forged numerous Nguni clans into a single realm, they had only encountered white men some fifty years earlier. Now, in less than a mans lifetime, the red soldiers were coming to enforce the White Queens rule.

For centuries there had been rare appearances of Europeans along this south-eastern coast of Zululand but they had been castaways, the survivors of tragic shipwrecks. Perhaps the first white men to set eyes on the rolling green hills and forested valleys, fringed with a shoreline of crashing breakers, were Vasco Da Gama and his Portuguese sailors. They did not set foot ashore in fact, for the next 300 years no one would deliberately do so but Da Gama nevertheless gave the land a European name, Natal, having sighted it on Christmas Day 1497.

Tides and winds ensured that unseaworthy ships, or ships with incompetent crews, were wrecked on a particular 500-mile-long stretch of the South African coast. It was as if a magnet drew the ships ashore there instead of elsewhere on a coastline over 2,000 miles in length. Many of the passengers and crew survived the numerous shipwrecks and got ashore some desperately injured but many unscathed. However, all were as one in their desperate plight. Their only hope of succour and rescue was to reach the Portuguese base of Loureno Marques, no more than a toehold on the African coast but blessed with a natural harbour, if little else, where Portuguese ships called at infrequent intervals.

The Nguni/Zulu people, far to the north, were amongst the last of the tribes to witness the tragic human remnants of the shipwrecks. By the time the survivors reached Nguni territory their numbers would have been decimated again and again by injury, murder, cannibalism, disease, starvation and despair. As few reached so far north, records of encounters with the Nguni/Zulu are rare; the survivors of the San Alberto, wrecked in 1593, were most likely the first white men to encounter them.

The San Alberto castaways also recorded that as they made their way further north, so the local people became increasingly friendly. On crossing the Uchugla River the present-day Thukela the Nguni/Zulu became so impressed with the fervour the Portuguese displayed during their religious devotions that they naively joined in with great abandon and rejoicing, kissing and embracing the Portuguese and treating them with the utmost familiarity. The Portuguese also found that mutual beard-stroking an affable form of greeting that they had encountered during their march north was also practised by the Nguni/Zulu.

1. Cetshwayo kaMpande, king of the amaZulu

In 1755 a handful of Englishmen, the first of what would become a massive invasion of Britons over the next 200 years, was thrown upon the shores of Zululand. Unlike the Portuguese ships that had met disaster on the return journey from India, the Doddington, a British East Indiaman, was wrecked on its outward voyage, three months after setting sail from England. She went aground near Algoa Bay (present-day Port Elizabeth) and so quickly did she sink that only twenty-three of the total ships company of almost 300 men and women survived.

Sixty years later, in preparation of a survey of the coast between Port Natal and Delagoa Bay, three ships of the Royal Navy dropped anchor off what is now Zululand. In 1819 Shaka, the illegitimate son of Senzangakhona, the ruler of the Zulu clan, had defeated the numerically superior Ndwandwe army of Chief Zwide kaLanga. It was the first of many victories that Shaka would win with a ruthlessness of purpose that, within a few short years, would establish the kingdom of the Zulu. Shaka saw to it that what had been an insignificant Nguni clan, would become the Zulu nation. He introduced a new form of warfare: instead of the opposing sides standing back, throwing spears at each other, Shaka invented a short, broad-bladed stabbing spear similar to the Roman sword of ancient times that was to be used hand-to-hand and thus retained. It was never to be thrown, on pain of death. The Zulus named this weapon iklwa, derived from the sucking sound made when the blade was withdrawn from a victim, but the Europeans used the term assegai for both this and the lighter throwing spear.