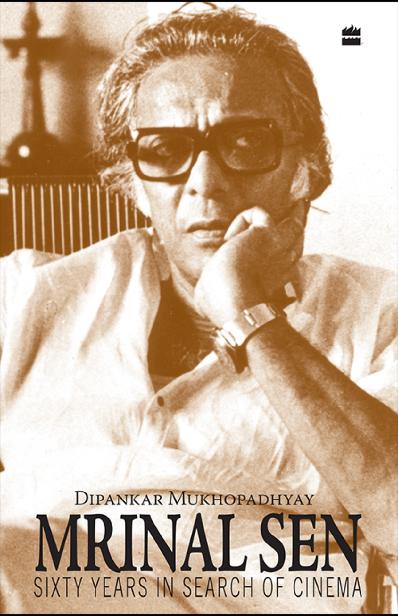

MRINAL SEN

S IXTY Y EARS IN S EARCH OF C INEMA

Dipankar Mukhopadhyay

HarperCollins Publishers India

With affectionate regards

To Gita-boudi,

an extraordinarily gifted artist

whose talents were grossly underutilized by

the film industry,

and who has been, for the last six decades,

a pillar of strength for her iconic husband

C ONTENTS

Pratap K. Das Gupta

Almost fifteen years ago, I wrote The Maverick Maestro when HarperCollins India, which had just started operations here, came up with an ambitious scheme to publish biographies of some eminent Indian film personalities to coincide with the centenary of cinema. The luminaries who figured in the list were, to the best of my memory, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy and Ashok Kumar. I had no quarrel over their greatness, but the absence of Mrinal Sens name in the list upset me immensely as I considered him the tallest personality of Indian cinema after the demise of Satyajit Ray, an opinion which has not changed in the intervening years. Not only did I send a strong letter to the publishing house, protesting against this arbitrary omission, but also volunteered to do the job myself if the company could not find a better candidate. I still do not know how it happened, but almost immediately I was offered the assignment. I had never written a book before; the only things I had going for me were almost two decades of journalistic experience, a few vital years spent in the promotion and development of Indian parallel cinema, and one and a half decade of intimacy with the subject of the book. If my memory serves me right, this was in early 1994.

I realized the difficulties once I started on the assignment. There was very little documentation available on Sen. I had to go through moth-eaten, dog-eared pages of journals and magazines of defunct and semi-defunct film societies and stray newspaper articles. In the beginning, Sen himself was not very enthused about the project. He must have been approached by many people for information on his life, none of which had obviously gone anywhere. Only after he saw the first few chapters did he open up. After that, I virtually shadowed him with a cassette recorder. But to my dismay, I found him not particularly organized. He had never bothered to keep a scrapbook, or a diary, so I was totally dependent on the memory of a seventy-two-year-old man. Here, I must gratefully acknowledge my debt to the late Mriganka Shekhar Roy, not only an eminent film critic but who had also worked as Sens assistant in his early years. A storehouse of information, he not only came up with interesting anecdotes, but also guided me to whatever documentation was available.

Another massive drawback was the non-availability of his films. Most of his prints were lying in pathetic conditions in various laboratories all over the country and there was nobody to look after them (this is true even today as seen from the cancellation of the retrospective of his films at Cannes this year owing to non-availability of good quality prints). The era of digitalization had not yet dawned, so all that he could give me for viewing was a bad videocassette of Matira Manisha. I had to write about his films mostly from memory as I had seen most of them and had been associated with some of them from inception. There was no point in looking at the scripts as Sen had the habit of shooting extempore, independent of the script.

In spite of all these problems and roadblocks, the book finally saw the light of day in October 1995 and, I am gratified to say, was appreciated not only at home but also abroad. Many foreign books published over the next decade referred to this book not only as Sens standard biography but also as a guidebook to the New Indian Cinema. Appreciation came not only from film circles, but also from unexpected quarters. I was floored when about five years ago I received a congratulatory letter from the then Deputy Prime Minister Shri L.K. Advani, expressing his happiness for this account of his Dear friend Mrinal, although politically and ideologically they were, and still are, miles apart. When I showed it to Sen, he also reciprocated the sentiment. Their friendship started during L.K. Advanis brief tenure as Information and Broadcasting Minister in the late 1970s and it was revived during Sens Rajya Sabha days.

About five years ago, the book somehow disappeared from the Indian market, although it still features prominently on Amazon.com, where one can obtain it by paying the princely sum of $28. I am immensely grateful to the present management of HarperCollins Publishers India, especially to its dynamic publisher and editor-in-chief V.K. Karthika, for the decision to reissue the book in the Indian market. Writing the text this time was much easier as there have been lots of publications and documentations on Sen after my humble beginning and I believe more will follow this year. Some of his major scripts are also available in both Bengali and English and, wonder of wonders, most of his films from the middle and later period can be easily obtained in DVD/VCD format, although it seems that most of the films he made in the first decade of his career are lost forever. Still, one must be thankful for small mercies.

At eighty-six, Sen may not be a maverick any more, but he undoubtedly remains a maestro. Only history will tell whether he will make another film. His spirit is very much willing and he is looking for a suitable story. But film-making is not only a cerebral activity, it involves considerable physical hardship. In the meantime, I am fortunate to get yet another chance to pay my humble tribute to this extraordinary man, internationally considered a modern master of the audio-visual medium, who, along with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, will always remain the third figure of the Holy Trinity of Indian cinema.

N EW D ELHI , M ARCH 2009

D IPANKAR M UKHOPADHYAY

Pratap K. Das Gupta

I first saw Mrinal Sen about twenty-five years ago, at the end of the first commercial screening of his film Interview. Clad in a slightly crumpled kurta-pyjama, he stood near the exit gate of a North Calcutta cinema house and bombarded the spectators as they trooped out: did they like the film, why and why not. Since it was the first day, first show, I had no preconceived idea or knowledge about the film. I expected something on the lines of Bhuvan Shome, but all the Brechtian alienation and cinema verite style of shooting totally confused me. I somehow managed to avoid the questioning director with a vague nod and a vaguer smile and rushed to Coffee House for a hot cup of stimulant.

Exactly ten years after that, the same gentleman in the same attire barged into my room at the Directorate of Film Festivals in Delhis Lok Nayak Bhavan. He introduced himself and told me that he had brought the print of his new filmit had a strange title: Ek Din Pratidin. It had to be despatched to Cannes for a preview. This was our first exchange, a strictly official one, but it soon spilled over to a typically Bengali adda . This soon became a habit. I particularly remember one occasion when he met me around three-thirty in the afternoon, and when I finally saw him off in a taxi, after going through a number of location changes in the course of our adda, it was one-thirty a.m.! Yet, after getting into the cab, he put his head out of the window and exclaimed, Delhi is not too conducive to adda. Come to Calcutta, we will have a grand session! And we had, not only in Calcutta alone. We had nightlong marathons at the Imperial Hotel in Delhi, the NFDC Guest House in Bombay, and even in distant Berlin. What fascinated me during those sessionswhich must have lasted a few hundred hours altogetherwas that he seldom spoke about anything other than cinema. It seemed that his whole existence was only for cinema and nothing else. I have never seen such complete devotion or dedication to ones profession before.