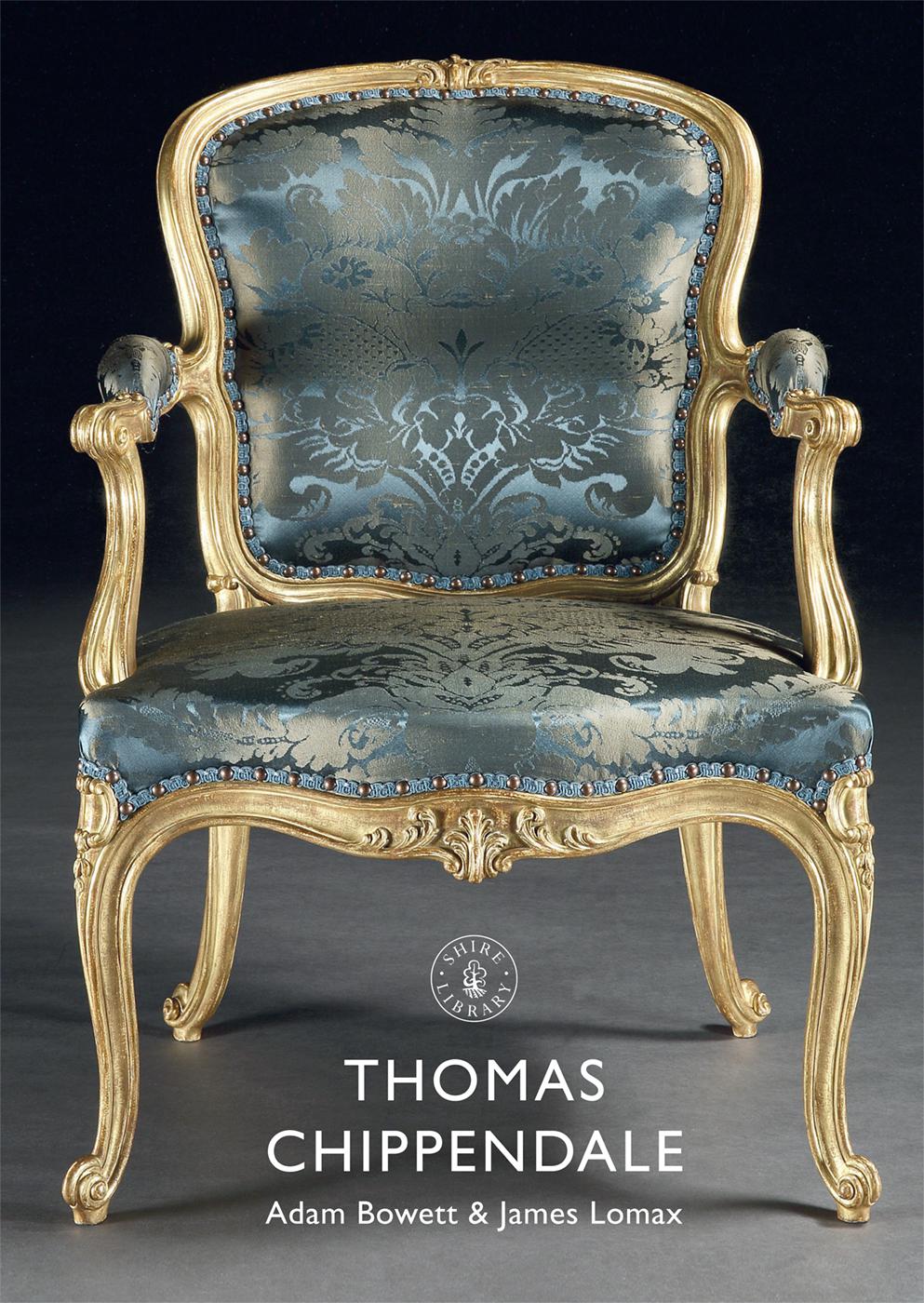

CONTENTS

THOMAS CHIPPENDALES LIFE AND CAREER

T homas Chippendale was born in Otley, near Leeds, and baptised in All Saints Church on 5 June 1718. He was the only son of John Chippendale and Mary Drake, who married in July 1715. John Chippendale was a carpenter/joiner, as were other members of his extended family in and around Otley. John Chippendales house is thought to have been on the site now occupied by the Skipton Building Society in Boroughgate, Otley. After Marys death in 1729 John remarried and had six more children, some of whose descendants still live in and around Otley today.

It is not known where Thomas was trained, but it is thought that, having received some initial tuition either with his father or with a relative, he went to York to be apprenticed to a cabinet maker. This was probably Richard Wood (fl.172672), who ordered eight copies of Chippendales Director when it was first published in 1754, four times more than any other subscriber.

Thomas retained his links to York and Yorkshire throughout his life, both through fellow tradesmen in York and Wakefield, and through the wealthy patrons whose houses he furnished. There is a traditionally held belief that some of his early career was spent working at Nostell Priory, near Wakefield, perhaps under the tutelage of the architect James Paine, but no evidence has yet been found to support it.

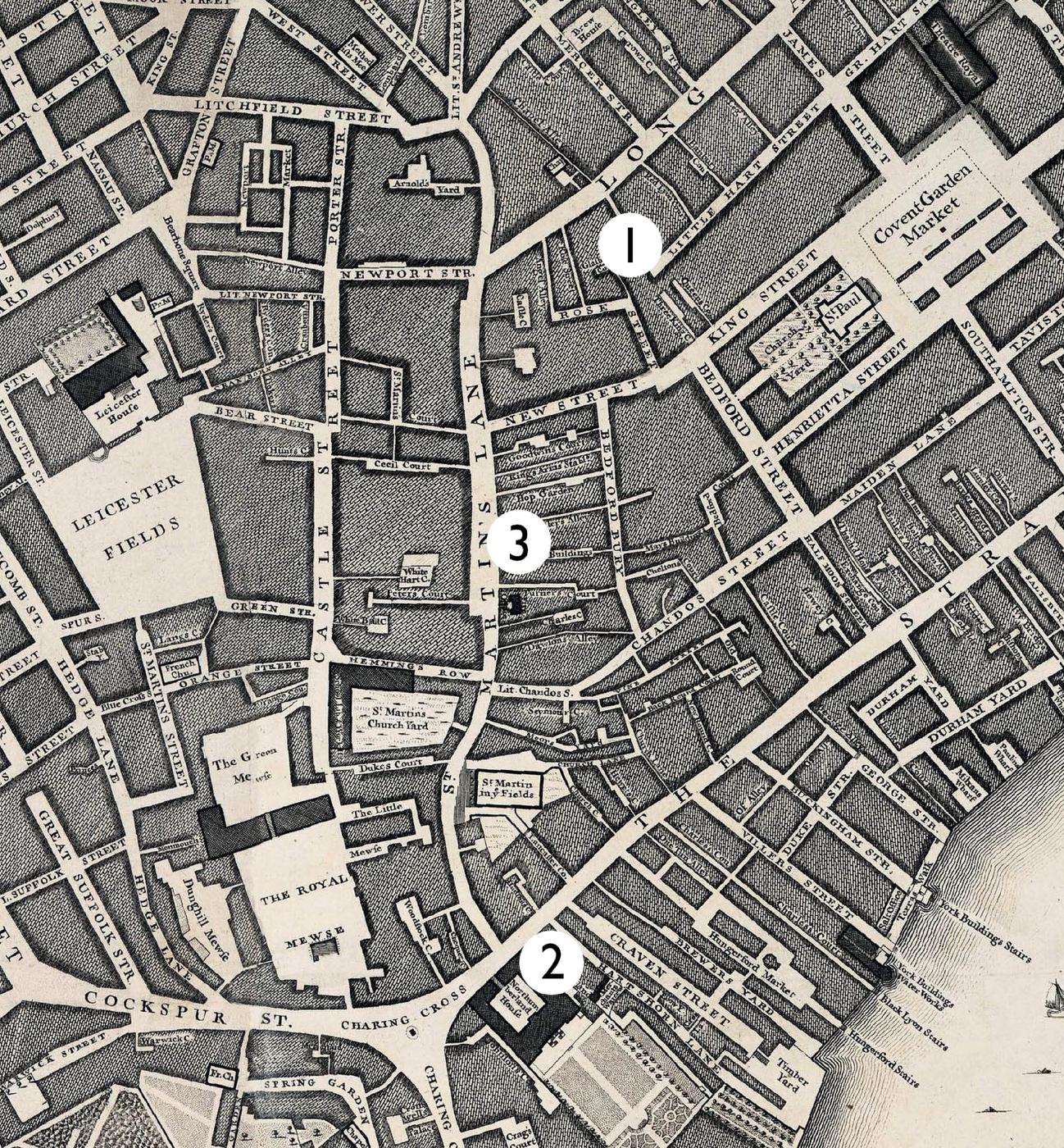

Nothing further is known about Chippendales life or work until, at the age of twenty-nine, he married Catherine Redshaw in St Georges Chapel, in Mayfair, London, on 19 May 1748. Their first child, Thomas Chippendale junior, was born in April 1749, and between Christmas 1749 and summer 1752 the Chippendale family lived in Conduit Court, off Long Acre. From there they moved to Northumberland Court off the Strand before finally settling in St Martins Lane in December 1753. Each move marked an increase in prosperity, indicated by the increase of the properties rateable value from 12 to 22 to 124.

All Saints Church, Otley, where Chippendale was baptised on 5 June 1718.

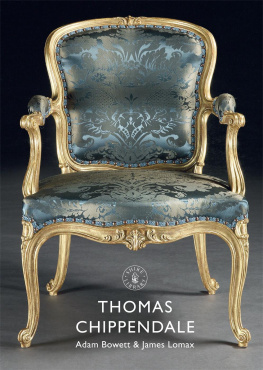

The few years between marriage and establishment in St Martins Lane were pivotal for Chippendale. He had developed a strong working relationship with the designer and engraver Matthias Darly and, either through Darly or some other tutor, had mastered drawing in the Rococo style with which his name is forever associated. He also conceived his plan to create the most comprehensive furniture design book yet published in England but, lacking the capital for such an ambitious venture, he formed a partnership with James Rannie, a Scottish businessman and entrepreneur. It was probably Rannie who provided the funds both to set up in St Martins Lane and to publish The Gentleman and Cabinet-Makers Director in 1754.

Chippendale claimed that he had been encouraged to publish by persons of distinction but of eminent taste, suggesting contacts with fashionable customers whom he may have encountered while working as a journeyman. As its title made clear, the book was aimed at both the buyers and the makers of furniture, to guide the one in the choice and the other in the execution of the designs. It was in effect a manifesto of contemporary Rococo taste in furniture, demonstrating the infinite variations which could be achieved by a skilled craftsman working in the Gothic, Chinese or Modern styles. Advertisements appeared in the press inviting pre-publication subscriptions for a large folio with 160 plates at 1 10s in sheets or 1 14s bound, limited to 400 subscribers. Thereafter it would sell at two guineas. In the event there were 303 subscribers named at the front of the book, of whom some 49 were from the nobility or gentry, plus a handful of professional men, academics and booksellers. The rest were all tradespeople. So successful was the venture that a second edition appeared in 1755, almost identical to the first.

Thomas Bowles, 1753, A View of Northumberland House, Charing Cross. Northumberland Court was the alley leading from the arch immediately to the left of the mansion.

London, 1746, showing: (1) Conduit Court, (2) Northumberland Court, (3) nos. 5961 St Martins Lane.

St Martins Lane, Westminster, with the church of St Martin in the Fields, showing the area before it was opened up to create Trafalgar Square.

The St Martins Lane premises comprised nos. 59, 60 and 61, on the right-hand side of the street going north from Charing Cross (no. 62 was eventually occupied by Thomas Chippendale junior in 1793). The street was at the hub of creative activity in London. Chippendales neighbours included the leading furniture makers William Hallett, William Vile and John Cobb, the sculptor Franois Roubiliac, the painter William Hogarth and the architect James Paine. Immediately opposite his premises was Old Slaughters Coffee House, which was a rendezvous for the artistic and artisan lite of London. The firms trade card described Chippendale and Rannie as Cabinet Makers and Upholsterers, indicating the wide range of services they provided. They could furnish and equip a whole house, from servants rooms in the attics to family apartments and grand state rooms, including wallpapers, curtains, carpets and kitchen equipment. Specialist work was probably out-sourced, including locks, handles and other hardware and perhaps marquetry. The firm even provided an undertaking service. Chippendale himself probably no longer worked at the bench, but was fully occupied in design, liaising with clients and quality control, while supervision of the different workshop departments was undertaken by a succession of experienced foremen. For important new commissions Chippendale would generally be recommended by the consultant architect, such as Robert Adam or John Carr. The architect would expect to be shown and to approve Chippendales proposals before they were executed.

Despite a serious workshop fire in April 1755 the furniture business thrived, and the first fully documented commissions (all Scottish) arrived in the late 1750s: from Lord Arniston (1757), the Duke of Atholl (1758) and outstandingly the Earl of Dumfries (1759). At the end of the decade, spurred on by a proposed new publication from his rivals, Ince and Mayhew, Chippendale prepared a third edition of the Director which eventually appeared in 1762. It contained 200 plates, 100 being entirely new, and included his vision of a fully mature Rococo style, while acknowledging the arrival of a new taste, the Antique style which we now call neo-Classicism.

By the mid-1760s Chippendales reputation was such that in November 1767 the London Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser called him that celebrated artist, Mr. Chippendale, of St. Martins Lane. But earlier, in January 1766, James Rannie had died, plunging the business into financial crisis. Chippendales money worries at this time are well documented, and it is probable that he never fully recovered from the financial damage caused by the demands of Rannies creditors. Stability only returned with a new partnership between Chippendale and Thomas Haig, the firms former book-keeper, in 1770. It also included the shadowy figure of Henry Ferguson, an erstwhile colleague of James Rannie.