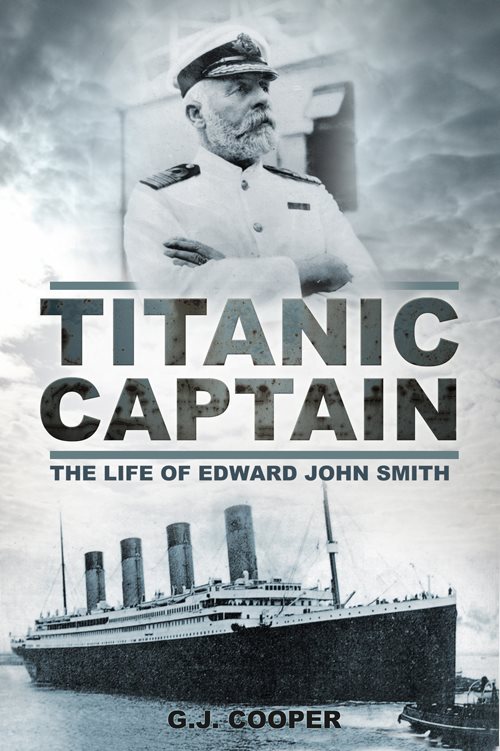

To my parents William and Barbara Cooper

and in memory of my uncle Peter Tomkinson,

the first historian in the family.

I t would have been difficult if not impossible to have written this book without the interest and assistance of a number of institutions and individuals. The author would therefore like to start by thanking the staff of the following establishments: the Maritime History Archive at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada; the National Archives, Kew, London; the Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool; the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; the New Brunswick Museum, St John, New Brunswick, Canada; Paris Smith LLP, formerly Paris, Smith and Randall, solicitors, Southampton; the University of Keele Library; Hanley Central Library and Archives; Liverpool Library; Lichfield Library.

The list of private individuals I wish to thank begins with Ernie and Pauline Luck who have pretty much been my co-conspirators in this work. Ernie introduced me to Captain Smiths family link with the Mason and Spode pottery dynasties, then went out of his way to trace the exact address of the house that Smith was born in and the credit remains with him for that. Both Ernie and Pauline also proofread a number of my chapters and prevented a few of my barbarisms getting into print. Via Ernie I would also like to thank a number of other people whose information contributed to this biography: the late Marjorie Burrett; Lyane Kendall; and Barbara Faruggio. I would also like to thank the members of the Masons Pottery Collectors Club for allowing me to give a talk on Captain Smith and for the many kind comments I received afterwards.

Another person who has my sincerest thanks is Norma Williamson, a descendant of Captain Smiths uncle George. Her research into her family history came as a pleasant revelation saving me a great deal of legwork and filling in a few otherwise embarrassingly large blanks in the Smith family tree.

Other individuals I wish to thank are: my friend and work colleague Paula Brown, who proofread several of my chapters and brought a number of points to my attention; Martin Biddle who helped me out of a number of geneaological holes; Steve and Gill Jones who provided me with the location of the grave of Smiths mother and were good enough to send me some photos; Susan M. Wickham who put me onto Kate Douglas-Wiggins memoirs; and in a very useful info swap, novellist Ann Victoria Roberts and her husband Captain Peter Roberts, master of the heritage steamship Shieldhall, pointed out a number of researchers and landsmans errors in my work that I had not noticed. G.W. Robinson, Geoffrey Dunster RD, RNR, and Lt. Commander Raymond J. Davies RD, RNR, contributed useful information to my earlier research and deserve to be thanked here still. So too does Jeff Kent, who many moons ago published my first book on Captain Smith. Two other individuals I would like to thank (though they may both have long since forgotten about me) are Biddie Garvin, who in 1987 during a college trip to Stratford to see a production of The Taming of the Shrew, gave me the idea for my first book on Smith and started me on this path; and Mike Disch, an American actor who in 2003 contacted me out of the blue for any insights I might have into Smith and rekindled interest in what for me had by that time become a rather dusty subject.

One major difference between this work and my original research, is that the online community has provided me with a wealth of research and opinions to draw upon, most notably on Philip Hinds excellent Encyclopedia Titanica website. Though I have by no means corresponded with all of the individuals listed here, to paraphrase Lightoller somewhat, their online comments, knowledge and good common sense in the face of much Titanic-related silliness has given me much guidance and food for thought and it would be churlish not to acknowledge the fact. I should note, though, that any opinions expressed in this work, are mine and mine alone. I would, therefore, like to thank, in no particular order: Inger Shiel, Mark Chirnside, Michael H. Standart, Erik Wood, Dave Gittens, David G. Brown, Bob Godfrey, Brian J. Ticehurst, Bill Wormstedt, Tad Fitch, George Behe, Addison Hart, Scott Blair, Samuel Halpern, Senan Molony, and Randy Bryan Bigham. Dustin Kaczmarczyk of the German Titanic Society contacted me privately pointing out a number of problems with my original text that needed addressing and has my thanks for that. Mark Baber, along with his many contributions to the Titanica site, also very kindly provided me with the fruits of his research showing that Captain Smith had been unfairly blamed for the grounding of the SS Coptic in 1889. Another community member, Parks Stephenson was good enough to contact me with information on the installation of Marconi wirelesses on White Star vessels, for which he too has my thanks. I have no doubt there are others, but it is difficult to recall everyone and should I have obviously missed anyone out they have my apologies.

Last, but by no means least, I would like to thank my family and friends who, without badgering me too much over the years, have continued to be interested in the progress of my research.

CONTENTS

1

H anley in North Staffordshire, where Edward John Smith, the future captain of the Titanic, was born in 1850 was one of six towns that by the time of his birth were known collectively as the Potteries. Only two centuries before, the district had not existed. Hanley and its near neighbours, Tunstall, Burslem, Stoke, Fenton and Longton, had still been a group of small moorland farming settlements, but the heavy upland soil and higher than average rainfall made for poor farming and circumstances had obliged the inhabitants to indulge in supplementary crafts to make ends meet. The local abundance of clay and coal had made pottery-making the natural choice in this respect and over time the locals had earned a reputation for the production of a wide range of domestic wares and pottery storage jars that were sold at the larger county markets. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution during the eighteenth century, these village crafts rapidly blossomed into full-blown industries and the small settlements had grown as people flooded into the area looking for work. So successful had the subsequent rise of the area been, that by the middle of the eighteenth century the six towns of the Potteries supplied the bulk of the pottery used in Britain and by the beginning of the nineteenth century the area was well on the way to dominating the worlds ceramic market.

Success, though, had come at a heavy price. As photographs of the Potteries in the nineteenth century reveal, 100 years of industry had produced a grim urban landscape and visitors to the area met with an interesting, if rather apocalyptic scene. When a German traveller, Johann Georg Kohl, first saw the district in about 1843, he was put in mind of an embattled line of fortifications. On approaching the Potteries from Newcastle-under-Lyme, the first thing he noticed was the thick cloud of smoke that spread out over the region. This poured from hundreds of factory chimneys and bottle ovens the distinctively shaped pottery kilns of the region of which dozens were often gathered close together looking, Kohl noted, like colossal bomb-mortars in the distance. The conical slag heaps of the local collieries, the high roofs of the drying-houses and warehouses and the thick walls that enclosed the factories, along with the piles of clay, coal, flint, bones, cinders and other matters lying scattered about, served only to strengthen the illusion. Nor did the Potteries diminish in interest as he passed its borders. In the sooty cobbled streets between the great factories, or pot banks as they are known locally, he spotted the small terraced houses of the workers, the shopkeepers, the painters, the engravers, the colourmen, and others, while here and there the intervals were filled up by churches and chapels, or by the grander houses of those who had grown rich as a result of the pottery industry.

Next page