All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

INTRODUCTION

I cant remember a time I was a child without also being a girl, a time I was a person before also being a female person. My mother told me a story about boys and girls, one thats taken on the weight of allegory for me: It was the summer before I turned four, and I was enrolled in a preschool called Magical Years. On a parent-chaperoned trip to the playground, my class put together a game of Peter Pan. My mother, with her long dark hair, was cast as Captain Hook. The moment the game began, the boys closed in, thwacking her as high up as their short arms could reach. The girls fled, yelling, Chase me, chase me! My mother was a diligent diarist in those years, and I asked her to look up her record of this day: The girls want to taunt me and have me chase them; the boys want to hit me and kill me and eat the parts. How, she wondered, had this happened? My mother went to college in the seventies; she worked, she was part of a generation of women who had fought to break down the barriers of traditional gender roles. Insidious, theyd seeped in anyway.

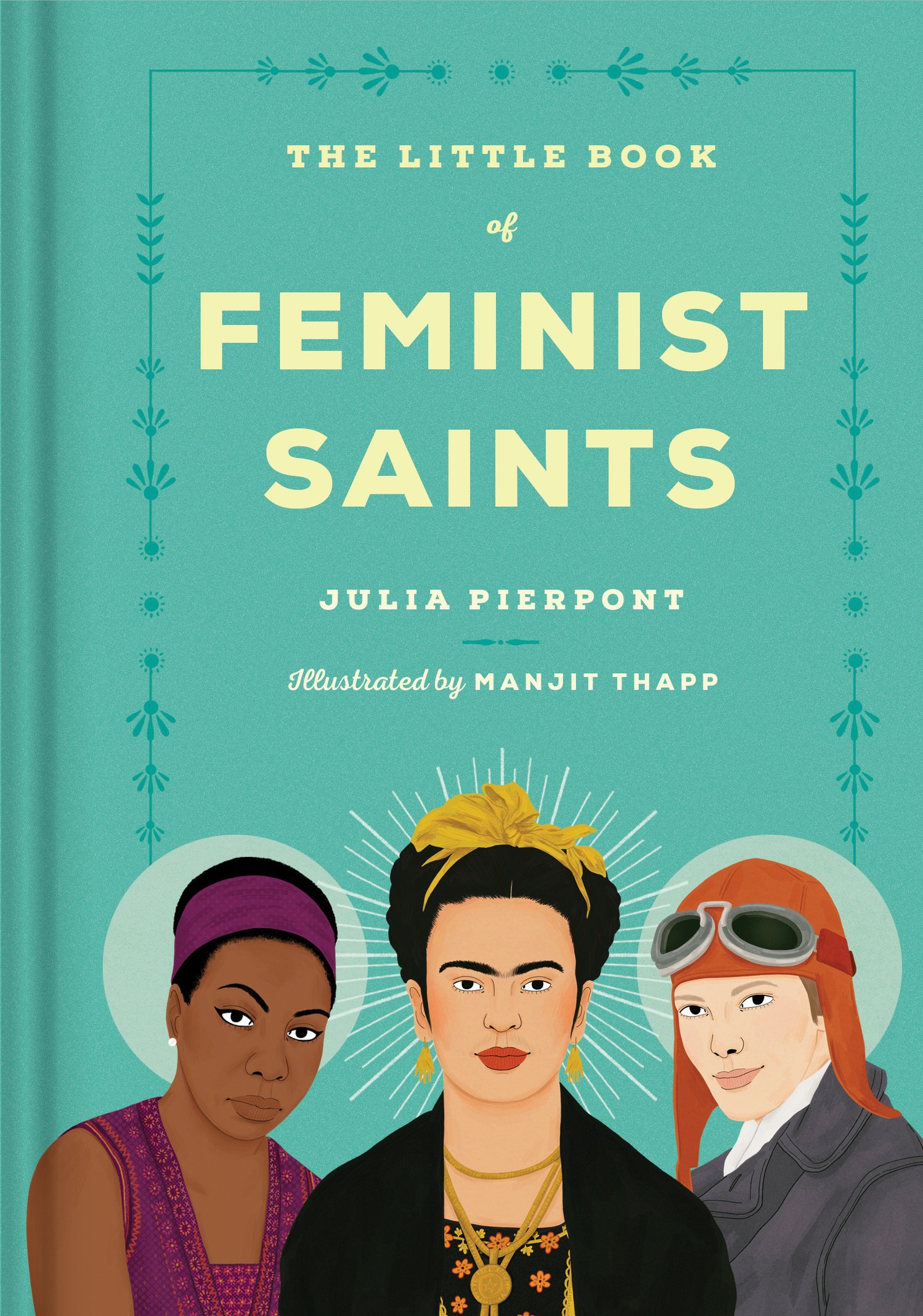

This is a book about women who flouted those roles, thank god, because the world would be a lot worse off if they hadnt. Comprising a hundred women, our list is by no means complete. Wemy editor, Caitlin McKenna, and Ibegan by compiling a few handfuls of names, those of women who had inspired and challenged us. Then we crowdsourced. My friend Jennifer Rice, in Austin, nominated Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to the United States CongressHer campaign button said CHISHOLM: READY OR NOT because she didnt give a damnand forty-fifth governor of Texas Ann Richards, who appointed women to everything. When Manjit Thapp came on board as our illustrator, she put forth such candidates as Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama and gay-rights activist Marsha P. Johnson. Caitlin got her friends and colleagues at Random House to contribute a terrific variety of names as well. Katharine Hepburn got five independent nominations, and Marie Curie eight. When the list had swelled to four hundred, we began the disagreeable task of winnowing it down. The hundred women who remain come from all over the world, ranging as far back in time as the Greek poet Sappho, born c. 630 B.C. , and as far forward as Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai, born in 1997.

So why, then, is this The Little Book of Feminist Saints, when the women within encompass all religions, or sometimes no religion at all? The idea came from the Catholic saint-of-the-day book, the kind one might read as a source of daily inspiration throughout the calendar year. Each woman in the book is assigned her own feast day, so that, for example, one might read about the banana-skirted Josephine Baker on June 3, the day of her birth. On Valentines Day, we celebrate Sappho and her poetry of desire. May 20 is for Amelia Earhart, who began her transatlantic solo flight on that day in 1932. Traditional Catholic saint books come with a complicated history. I happened upon an account of one such book of saints while reading about Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant ruler in a previously Catholic country. When the dean of St. Pauls gave her the gift of a prayer book with pictures of saints, she rejected it. You know I have an aversion to idolatry, she told him. I would argue that all the women in this book have done something with their lives that makes them worthy idols. So let this be the little, secular book of feminist saints.

These entries are not meant to serve as short biographies, summaries of each womans life that could just as easily be found online. I tried, instead, in my daily research, to zero in on the colorful, the anecdotes I would find myself repeating to a friend that night. Connections began to emerge among the women as well. Some links were indirect: at the Chicago Worlds Fair in 1893, while Mary Cassatts feminist mural Modern Woman was causing a stir within the exhibition, Ida B. Wells was just outside, boycotting the fairs omission of the African American community. As time went on, and the world got smaller, there were occasions of direct support among them. When Gloria Steinems Ms. magazine debuted, in 1972, featuring a petition titled We Have Had Abortions, the first lady of tennis, Billie Jean King, was among its fifty-three signees. When Ruby Bridgeswho, in 1960, became the first African American child to attend an all-white Louisiana school following Brown v. Board of Educationwas reunited, thirty-six years later, with her first-grade teacher, it was on a talk show helmed by the Queen of All Media, Oprah Winfrey. I had the feeling of stumbling upon a great sisterhood.

There is another entry in my mothers diary, written a month earlier: It was an unusually warm day in February, and we were at the schoolyard, playing Peter Pan then, too. I was Captain Hook, my mother wrote. Julia was Michael and John, Gabriella the crocodile, Lindsay was Wendy, and tiniest Antonia, whom we met there, was Pan. What is remarkable about this entry, apart from my mothers meticulously recorded cast list, is that there were no boys in the group that day, and so, like water, we girls filled the new space wed been given. The women in these pages made and filled their own spacesvery often, big spacesfrequently when they hadnt been afforded any at all.

MATRON SAINT OF ARTISTS

B. 1593, ITALY

Feast Day: January 1

The judge ordered them to use thumbscrews, to ensure that the victim was telling the truth. There were gynecological exams in court, to confirm that her virginity had been, as she claimed, taken from her. The trial dragged on for eight months, during which time Artemisia never wavered from her testimony: Agostino Tassi, a painter her father had hired to act as her tutor, had raped her. In the end, Tassi, whod been accused of rape before, was given a one-year sentence that he was never made to serve, and Artemisia was married off, quickly and quietly, and sent away, to Florence, where her real lifes work began. She could neither read nor write, but she could paint. And she did paint: powerful women, women seeking revenge. Her best-known work, Judith Slaying Holofernes, depicts the Old Testament story of the widow Judith decapitating the general Holofernes, with remarkable violence. But it was her own face she used for Judith, and for the face of Holofernes, she painted Agostino Tassis. It is the work for which he is remembered now, a man who was meant to be her tutor, and instead became her subject.