For Corbett Sionainn, living proof that Colorado

continues to produce remarkable women.

Copyright 2002, 2012 by Morris Book Publishing, LLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford CT 06437.

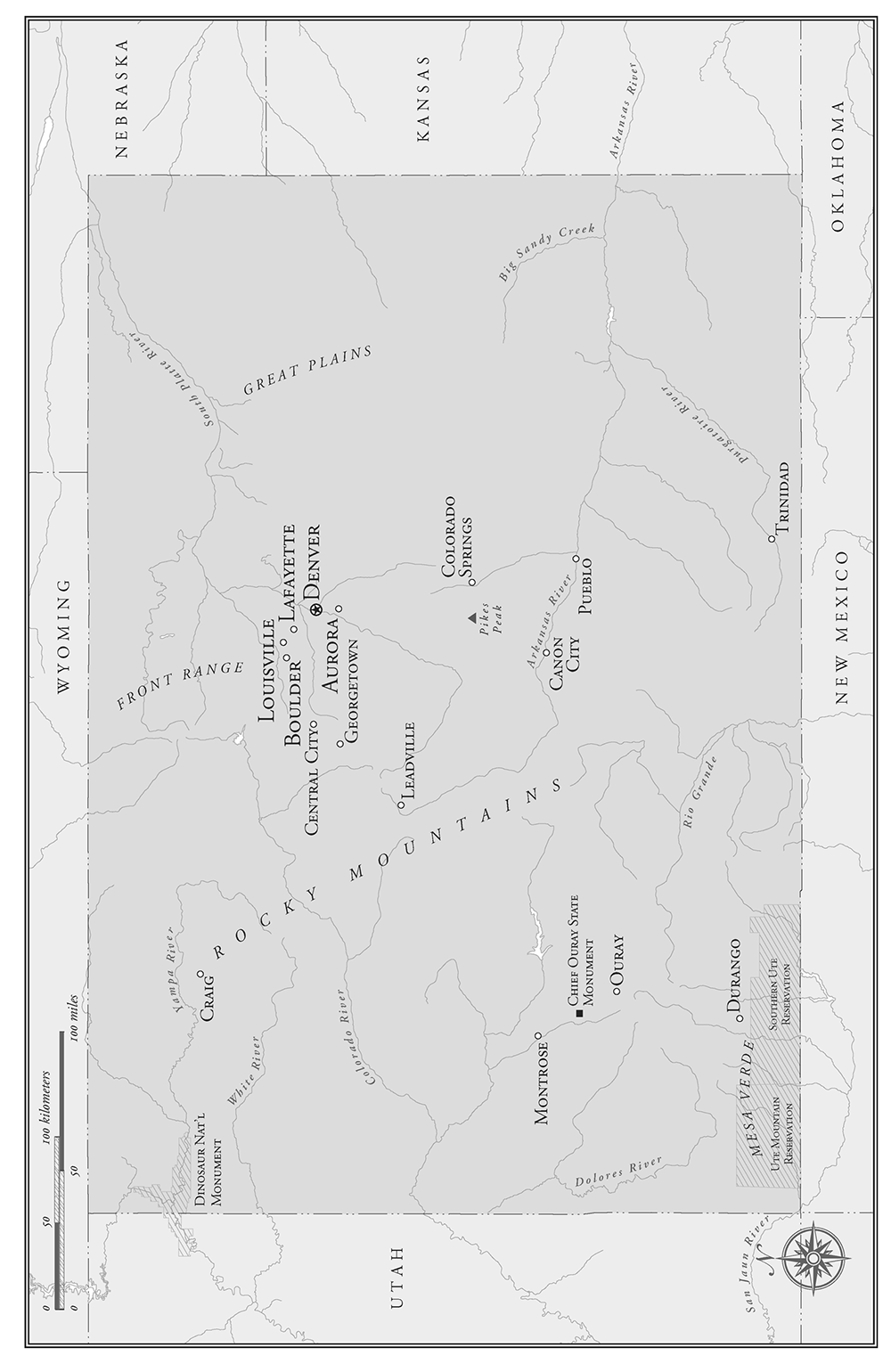

Map by Daniel Lloyd Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Sue Murray

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-6444-0

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for the assistance of the following:

The staff of the Lewis and Clark County Library in Helena, Montana, was always courteous and helpful in looking for the many books and articles I requested through its interlibrary loan program.

The staffs of the Western History Department of the Denver Public Library, the Colorado Historical Society, and the Uintah County Library Regional History Center in Vernal, Utah, were very helpful in nailing down elusive details and providing photographs of these remarkable women.

Gerald R. Armstrong of the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company in Denver liberally offered information on Josephine Roche.

Millie Arvidson, manager of Matchless Mine-Baby Doe Tabor Museum at Leadville, provided information on Baby Doe and the museum.

Staff members at Dinosaur National Monument, the Molly Brown Museum in Denver, and the Ute Indian Museum in Montrose were also helpful.

INTRODUCTION

There is an adage that men make history, but women are history. That certainly was the case for all too many generations. For two centuries after our forefathers gave birth to our nation, presumably without the help of foremothers, every American student studied a history made up of kings, presidents, emperors, and generals. History books were laden with patrilineal family trees, etchings of famous male warriors and leaders, and maps of battlefields where men slaughtered other men as they conquered new lands.

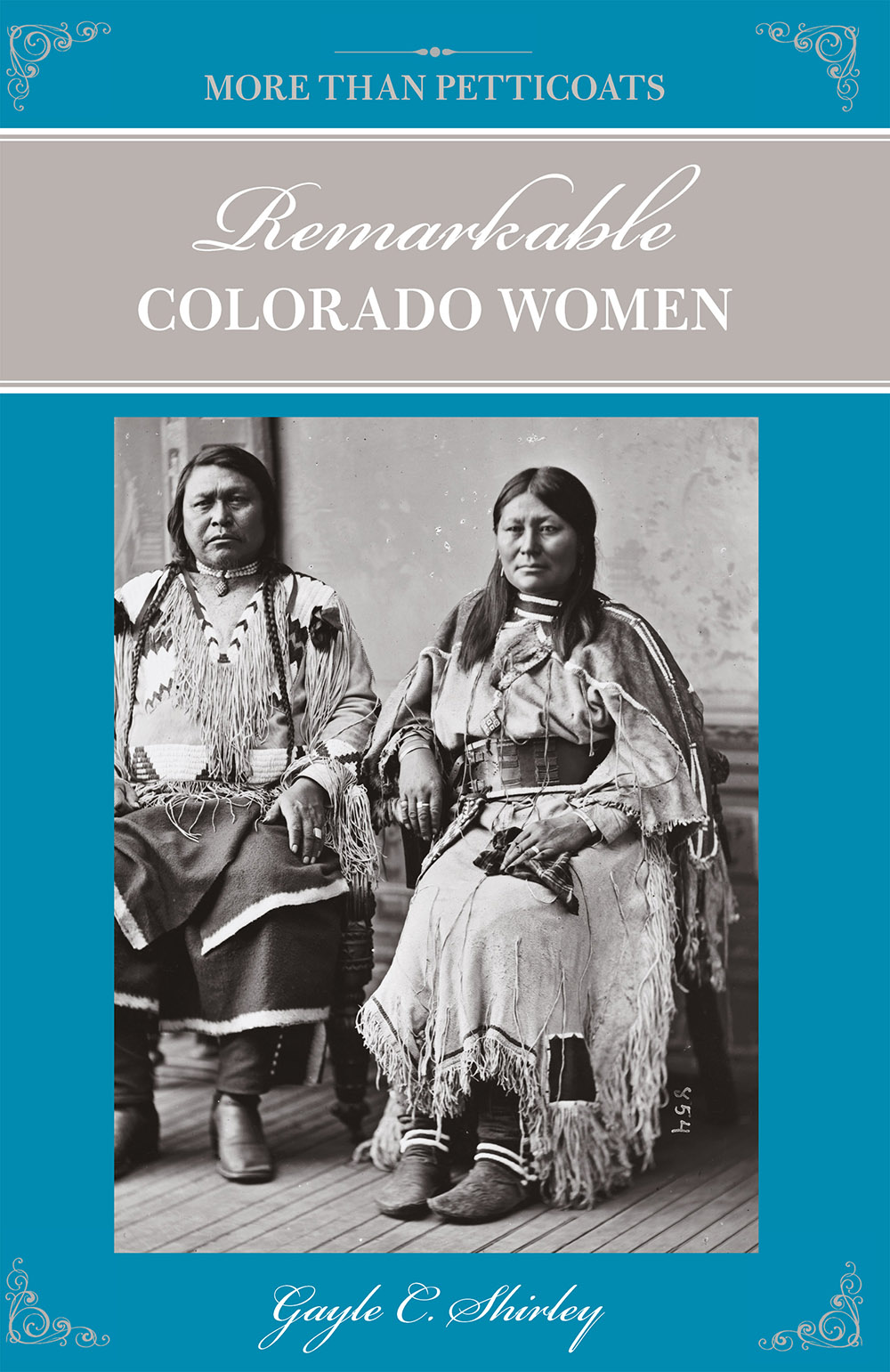

But in the 1960s and 1970s, women did make history. In the course of what became known as the Feminist Revolution, they demanded recognition for their value and contributionstoday, tomorrow, and yesterday. In the decades since, historians have begun taking a serious look at the role women played in building our nation. Eventually, they trained their spotlights on women of the Westthose who came by steamboat, train, and covered wagon, and those who were here already.

At first, scholars shuffled western women into convenient pigeonholes. There was the idealized Madonna of the prairies, a long-suffering pioneer wife and mother who gamely toiled across the Great Plains in calico and sunbonnet. There was the disreputable soiled dove, an enterprising floozy who made her living in hurdy-gurdys and houses of ill repute. And there were the maiden schoolmarms, the servile squaws, and the pistol-packing Calamity Janes.

But as historians unearthed letters and diaries left behind by flesh-and-blood frontier women, and as they learned more about the American Indian and Hispanic women who were here even earlier, they discovered that there were no convenient stereotypes. The women of the Old West were as diverse as the Colorado mountains and plains. They came from different backgrounds, had different experiences, and responded to frontier life in different ways.

For some, the move West was like taking off a corsetvery liberating. The frontier offered new chances to express their individuality. For another group of women, the West was a land of privation and hardship, where the struggle to survive overwhelmed other desires. Still other women attempted to make the West an extension of the life they knew back East. They brought with them all the repressive baggage of the cult of true womanhood, which demanded that they be pious, pure, submissive, and domestic.

If there is one truth about frontierswomen, one historian contends, it is that they were not any one thing.

This wealth of diversity is apparent in this book, which celebrates many remarkable women who made their mark on Colorado history.

One hazard inherent in writing about the past is the tendency to view historical events from a contemporary perspective. Yet, how can we do otherwise? Were all products of our times. Values and attitudes change, and what may have been socially acceptable a century ago may not now be politically correct. This is especially apparent with regard to women and minorities.

Ive tried to keep modern sensibilities in mind as Ive written this bookbut not at the expense of historical accuracy. For how can we judge how far weve come if we refuse to acknowledge where weve been? The fact is, women and minorities were considered inferior a century ago, an attitude that may be reflected in some of the quotations I use in this book. That we know better today doesnt mean that its our job to erase incidents of sexism and racism from our history books and pretend they never happened. Our responsibility, I believe, is to recognize them for what they were and demonstrate with our own behavior that civilization has made progress.

When I began work on this book, my first challenge was to identify a dozen or so women who were worthy of inclusion in it. I wondered if I could find enough. But as I dug into historical archives, I developed a new worry: How was I to decide which of the countless fascinating Colorado women to include? How could I be sure I wouldnt overlook someone important?

To keep the book a manageable size, I chose to limit it to women born before 1900. I also tried to choose a cross section of women who excelled in various fieldsfrom journalism and charity to business and science. Some were feminists and activists, but others simply were women without political agendas who stood out among their peers.

Obviously, I couldnt include all of Colorados remarkable early-day women. Among the intriguing people I left out were Emily Griffith, who founded Denvers famous Opportunity School; Helen Hunt Jackson, who wrote Ramona and other popular books; Josephine Meeker, who survived a kidnapping by Ute Indians; Dr. Susan Anderson, who provided health careoften freeto Fraser Valley residents for almost half a century; Katherine Lee Bates, who wrote America the Beautiful after being inspired by the view from the top of Pikes Peak in 1893; and Mary Cronin, the first woman to climb all fifty-one Colorado peaks over fourteen thousand feet high. This book also could have featured at least two former Colorado residents who starred on the international stage: Golda Meir, Israels fourth prime minister, and former First Lady Mamie Dowd Eisenhower. All these womenand many morehave fascinating stories, and I regret having to leave any of them out.