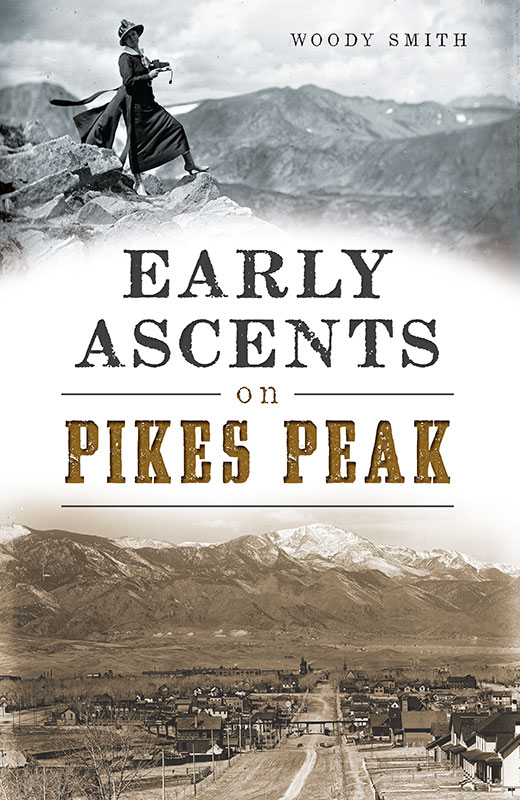

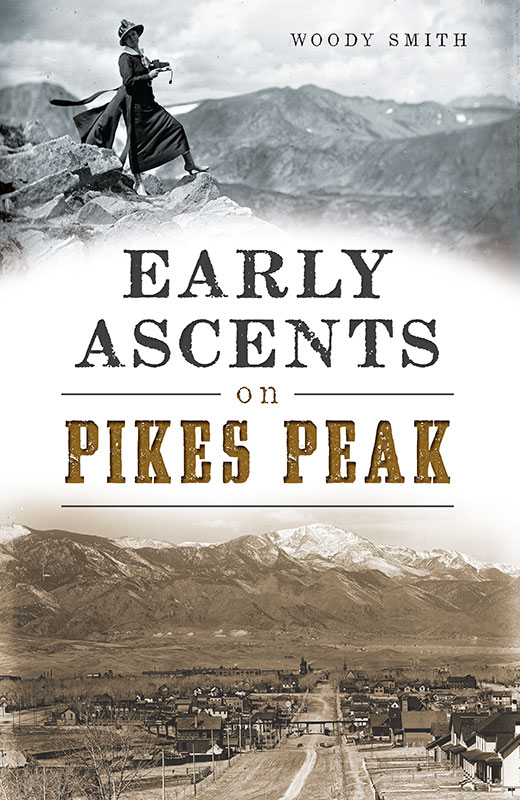

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Woody Smith

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.589.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942729

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.839.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Mom and Dad.

Thanks for the good brain.

CONTENTS

Pikes Peak Summit. Photo by Haines Photo Co., August 21, 1908. Library of Congress.

FOREWORD

Pikes Peak was once the most widely known mountain in the American West. Zebulon Pike failed to reach its summit in 1806, but by the latter half of the nineteenth century, thousands did so annually. The rush toward the peak began after hardy argonauts painted signs of Pikes Peak or Bust on their wagons. They headed west in search of gold but were not entirely sure of the peaks location relative to the gold fields. Once they had crossed the plains, however, there was no mistaking the mountains prominence.

With no other mountains of similar height within a sixty-mile radius, massive Pikes Peak stood as an undisputed landmark. It became a beacon for all who followed. Some pushed past the mountain seeking gold and silver discoveries. Others settled along Colorados Front Range and in the new town of Colorado Springs. But these were just the vanguard.

Railroads soon brought flocks of tourists to the base of the mountain. While a few adventurers roamed the peak in all seasons, tourists sought the easiest route to the summit in summer. The mountain soon became a must on the Colorado tourism circuit. First on foot and by horseback and later by horse-drawn carriage and cog railway, hundreds, then thousands and then tens of thousands reached its lofty top. Many summiteers returned east boasting, Yes, of course, they had climbed Pikes Peak.

The main ascent route by foot or horse evolved into the Barr Trail. Running from Manitou Springs to the 14,110-foot summit, the trail climbs 7,500 vertical feet in almost eleven miles and remains a grueling one-day outing. A carriage road was constructed to the top in 1889, and the following year, the Manitou and Pikes Peak Cog Railway was completed to the summit with grades approaching 25 percent. By 1915, an automobile road had replaced the old carriage route.

If one reaches the summit of Pikes Peak on a cold and foggy day and thick clouds encircle the mountain, one may wonder what all the fuss is about. But on a clear day, the views eastward across the plains, westward into the verdant expanse of South Park or north and south along the Front Range awe many a visitor. No wonder that after an 1893 visit, Katherine Lee Bates was inspired to write the words that became America the Beautiful.

Woody Smith has prowled the archives, newspapers and photo collections of Colorado libraries to assemble an intriguing, firsthand look at what it was like to ascend Pikes Peak and experience the mountain in the early days. Here are stories of tranquil summer outings and posed photographs. But there are also far more rigorous tales of danger during the icy blasts of winter or an ill-fated search for rumored treasure. In such a wild and beautiful place, death was sometimes right over the next rise.

Lace up your boots, straighten your tie or long skirt and step back into the nineteenth century for a trip up one of Americas most storied mountains.

Walter R. Borneman is the co-author with Lyndon J. Lampert of A Climbing Guide to Colorados Fourteeners, first published in 1978 and in print for twenty-five years. His 2005 book with acclaimed photographer Todd Caudle, 14,000 Feet: A Celebration of Colorados Highest Mountains, remains a Colorado favorite. Bornemans other books include The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy, and King; American Spring: Lexington, Concord and the Road to Revolution; and Iron Horses: Americas Race to Bring the Railroads West.

FOREWORD

There is the story about Zebulon Pike. When he was out with his small army group, they kept getting lost. At one point, it is told, they planned to go west but went by their compass and headed south, where a Spanish army detachment captured them and held them briefly. Historians found that they had a compass made by the Tate Company in Boston. It seemed to function properly. From this there came a saying: He who has a Tates is lost.

I understand that Zebulon was fairly even-tempered, but now and then something would really irk him. This was known as Pikes Pique.

Woody Smith has performed a wonderful archival feat to rescue accounts of exploits on Pikes Peak in the nineteenth century. Included are verbatim descriptions of early, often harrowing, climbs in all kinds of weather; extensive reports of lightning phenomena; the first death-defying descent via bicycle; and many deaths, some by murder. Readers will find fascinating the very words of these pioneers and newspaper accounts of the day.

Al Ossinger was the 101st person to report climbing all of Colorados fourteen-thousandfoot peaks (August 1969). Since joining the Colorado Mountain Club in 1965, Al has been club president (1986), served on the CMC Board (198386), led at least 154 trips (197291) and served as chairman of the Winter Activities Committee (198488). He has also written for the CMC magazine Trail & Timberline. Al has climbed over four hundred fourteen-thousand-foot peaks.

FOREWORD

When I retired in Pueblo, Colorado, in 1976, I used to occasionally make an early morning drive to Manitou Springs and walk up the Barr Trail to the top of Pikes Peak, where Id have coffee and a couple of donuts and then ride the cog down or hitch a ride on a tourist bus. Sometimes I would encounter a guy from back east who came out to Colorado Springs every summer and sometimes walked up Pikes Peak two or three times in one day. I was amused when the army paid no heed to his offer to walk up the mountain four times in one day if they would make him the loan of a helicopter. Once, I shared a seat with him on the cog, and he asked what he might do to get the Colorado SpringsPikes Peak area more attention. Tongue in cheek, I suggested that he walk up the trail naked, but he didnt think that was funny. Anyway, I was not interested in any challenges or marathons. Those walks were pure enjoyment, and I was grateful to Fred Barr for having built the trail.

Woody has artfully and skillfully compiled a lot of information about the early days, and I have scanned an advance copy with interest; I look forward to its publication.

Paul Stewart has been a member of the Colorado Mountain Club since 1954. He joined so he could attend that years summer outing to Mount Holy Cross, whose co-leader was climbing legend Carl Blaurock. They remained friends until Blaurocks passing in 1993 at age ninety-eight. Stewarts other CMC activities include leading nearly 130 CMC trips all over the state between 1965 and 1990 and serving as editor of the CMC magazine

Next page