I am deeply grateful to all those who helped make this volume possible, especially my husband, Harold. Hannah Carney, my editor, deserves great credit for her kind and expert guidance; Laurie Wagner Buyer for her editing; and friends Andy Weinzapfel, Ann Carlisle, Bill Arbogast, and Bridget Ambler for their support. Frank Ross of Coffrins Old West Gallery in Bozeman, Montana, made possible the exquisite images from L. A. Huffman. Finally, I am sincerely grateful to all of my friends from the First Nations for their help with this work, including Loya Arrum, Clifford Duncan, Jimmy Arterberry, Ben Ridgley, and Wankiyan Sna Mani. Thanks also go to Neil Cloud, Gordon Yellowman, Lorene Willis, and Billy Evans Horse. Unless otherwise noted, images are from the authors collection.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cassels, E. Steve. The Archaeology of Colorado . Boulder, CO: Johnson Publishing, 1990.

Coel, Margaret. Chief Left Hand: Southern Arapaho . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

Goodman, Ronald. Lakota Star Knowledge . Rosebud, SD: Sinte Gleska University, 1992.

Grinnell, George Bird. The Fighting Cheyennes . North Dighton, MA: JG Press, 1995.

Haley, James L. Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Hassrick, Royal B. The Sioux . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Mens Worlds . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Kroeber, Alfred L. The Arapaho . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

Mendosa, Patrick M. Song of Sorrow: Massacre at Sand Creek . Denver, CO: Willow Wind Publishing, 1993.

Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

Robinson, Charles M. Bad Hand: A Biography of General Ranald S. MacKenzie . Austin, TX: State House Press, 1993.

Simmons, Virginia M. The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico . Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2000.

Smith, Anne M. Ethnography of the Northern Utes . Albuquerque, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1974.

Swanton, John R. The Indian Tribes of North America . Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1969.

Tiller, Veronica E. Velarde. The Jicarilla Apache Tribe . Albuquerque, NM: Bow Arrow Publishing, 2000.

Wallace, Ernest, and E. Adamson Hoebel. The Comanches: Lords of the South Plains . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.

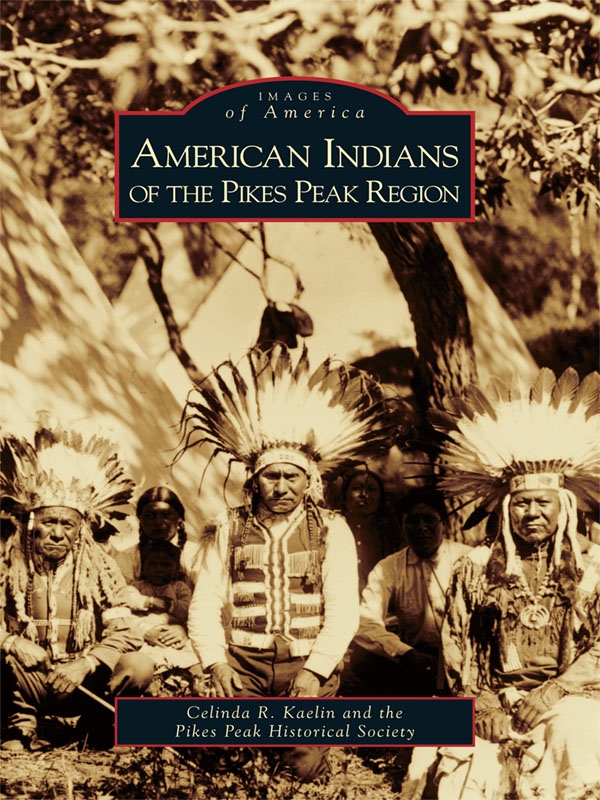

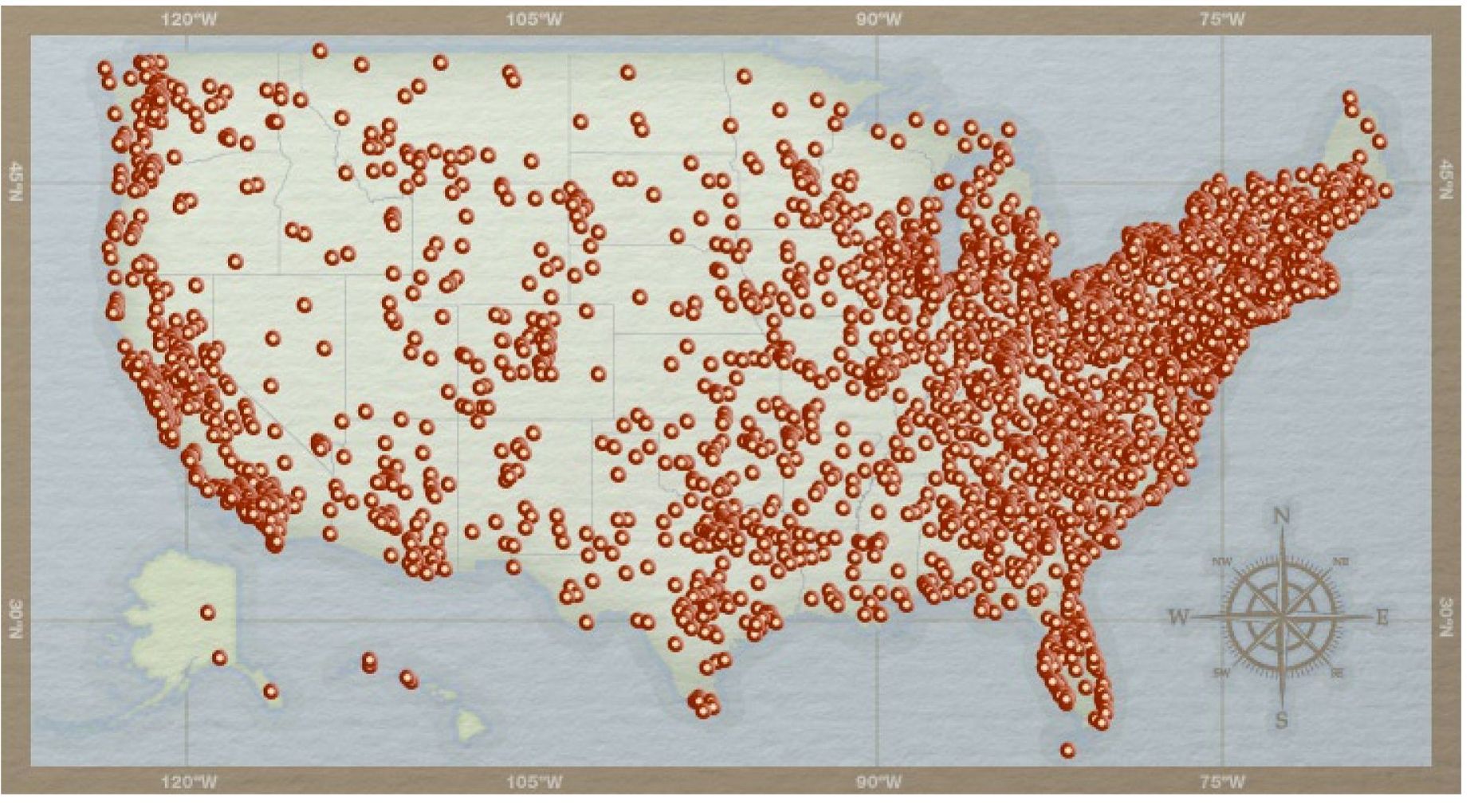

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

PREHISTORIC PEOPLE OF THE PIKES PEAK REGION

We have no way of really knowing what language was spoken. They left no written record other than mysterious, pecked images on well-weathered stone. These are the ancient people of the Pikes Peak region, occupying the area from at least 12,000 years ago. Maybe they were created here. Or maybe they were an ancient migration of the Olmec culture from Central America. Or maybe they came by sea, island hopping along the Bering Strait.

Whoever these first people of Pikes Peak were, they left many intriguing mysteries. In the 1930s, famed anthropologist E. B. Renaud performed the first scholarly study documenting Paleo-Indian presence in the Pikes Peak region from about 10,000 BCE. Meanwhile, on the west slope of the peak, an ethnological survey at Mueller State Park included finds of Paleo-Indian and Archaic stone tools. A little farther west, near the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Renauds team found Yuma and 12,000-year-old Folsom points, as well as tipi rings, stonework shops, and campsites.

On the east flank of Pikes Peak, archaeologists found evidence of human occupation from 5,000 years ago on Turkey Creek at Fort Carson. At the Air Force Academy, scientists uncovered a prehistoric stone circle with charcoal dating back 830 years. They also found a brush structure with 310-year-old charcoal. At Garden of the Gods, prehistoric etchings from at least 1,000 years ago mark the presence of these first people. They also left a fire pit in an arroyo about 3,500 years ago.

Finally, east of Colorado Springs, near Jimmy Camp Creek, there is evidence of numerous prehistoric occupations. Among these, one is dated from 665 CE, a second from 1400, and a third from 1650.

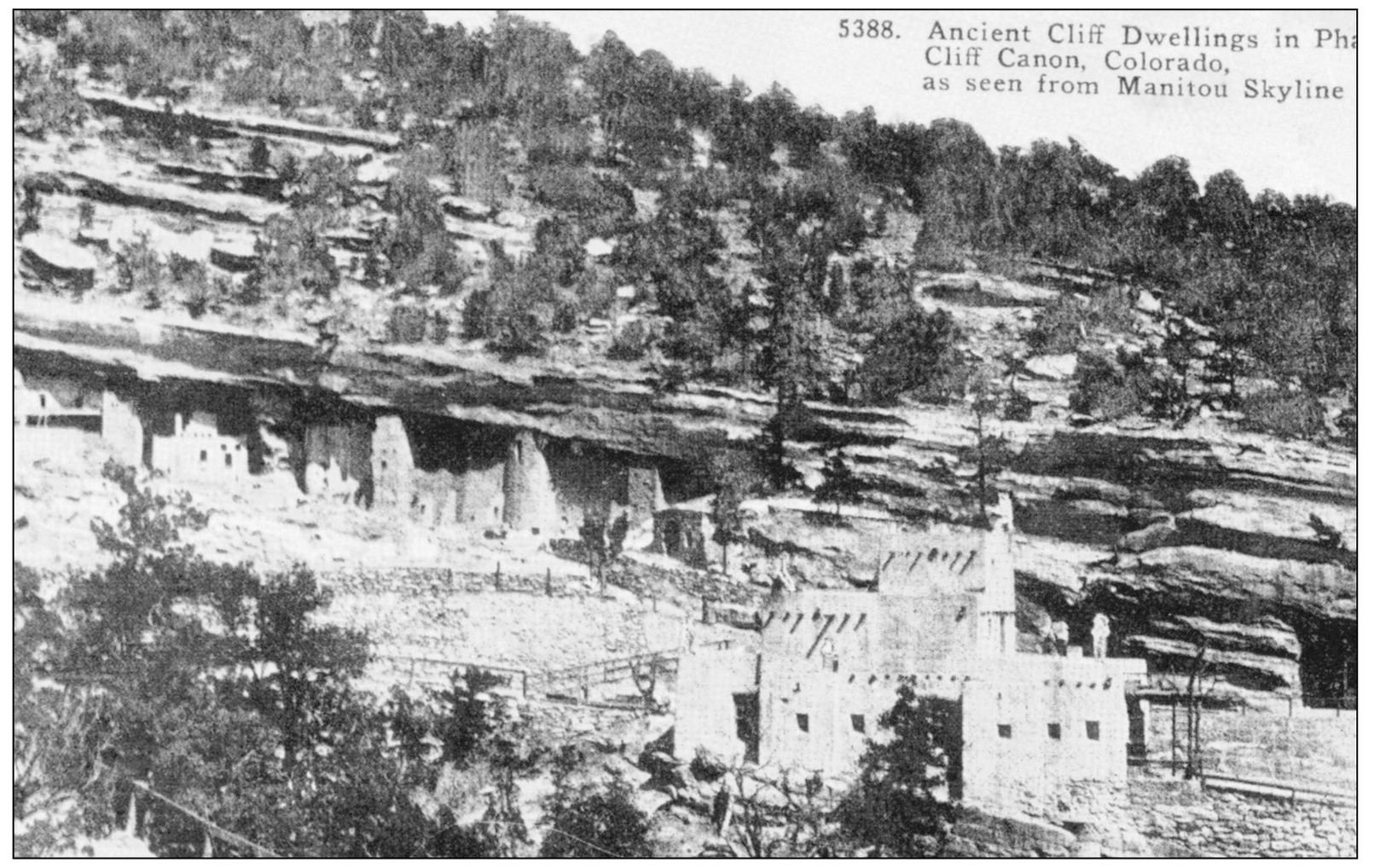

These cliff dwellings off Highway 24 north of Manitou Springs are authentic of prehistoric people, though not authentic to their location. In the early 1900s, some enterprising residents moved these Anasazi dwellings from the Mesa Verde area and had them reconstructed at their current site. (Courtesy Ute Pass Historical Society.)

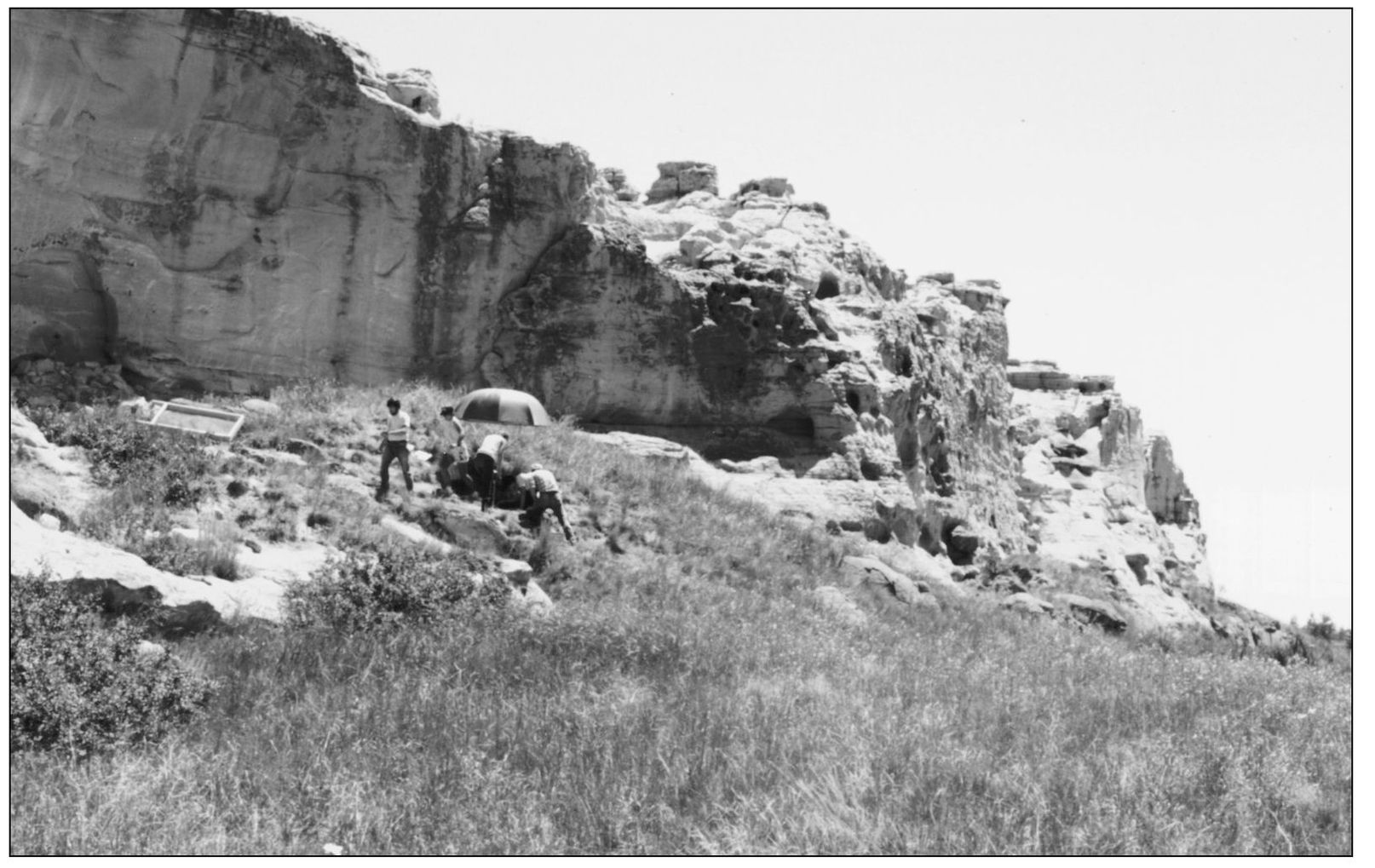

Archaeologists examine evidence from a mid-Archaic (about 6000 BCE) to late-Ceramic (about 1700 CE) bison jump at Crows Roost, east of Colorado Springs. Early people drove herds of buffalo over this steep cliff, leaving behind the stone and bone tools used to process the meat. (Courtesy University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.)

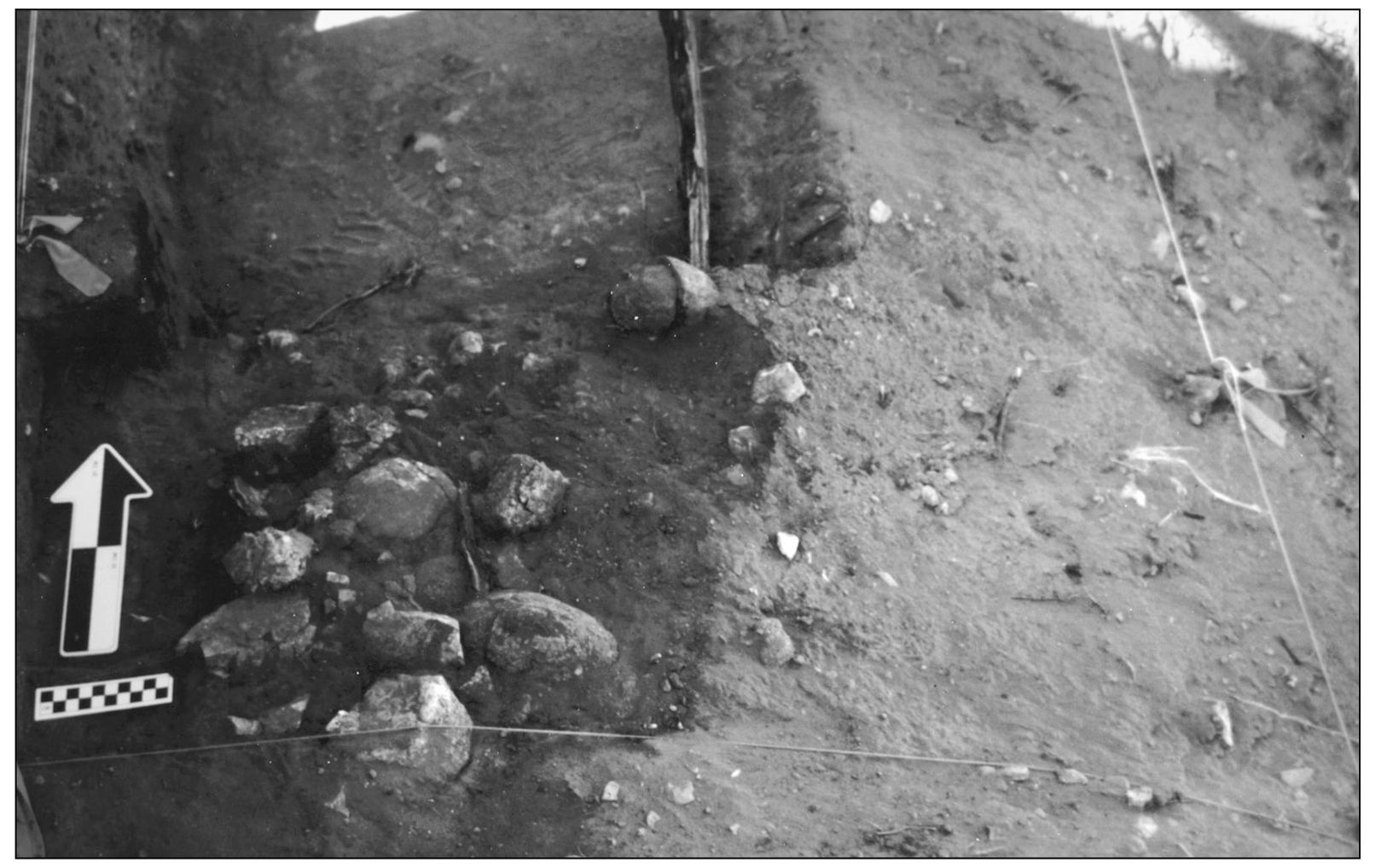

Rain, dust, and erosion buried this prehistoric hearth for more than 8,000 years at Garden of the Gods. Stones from the hearth are clustered in the center of the photograph. Rain has eroded the hillside, giving a nice profile of a fire pit that once warmed an ancient hunter and his family. (Courtesy University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.)

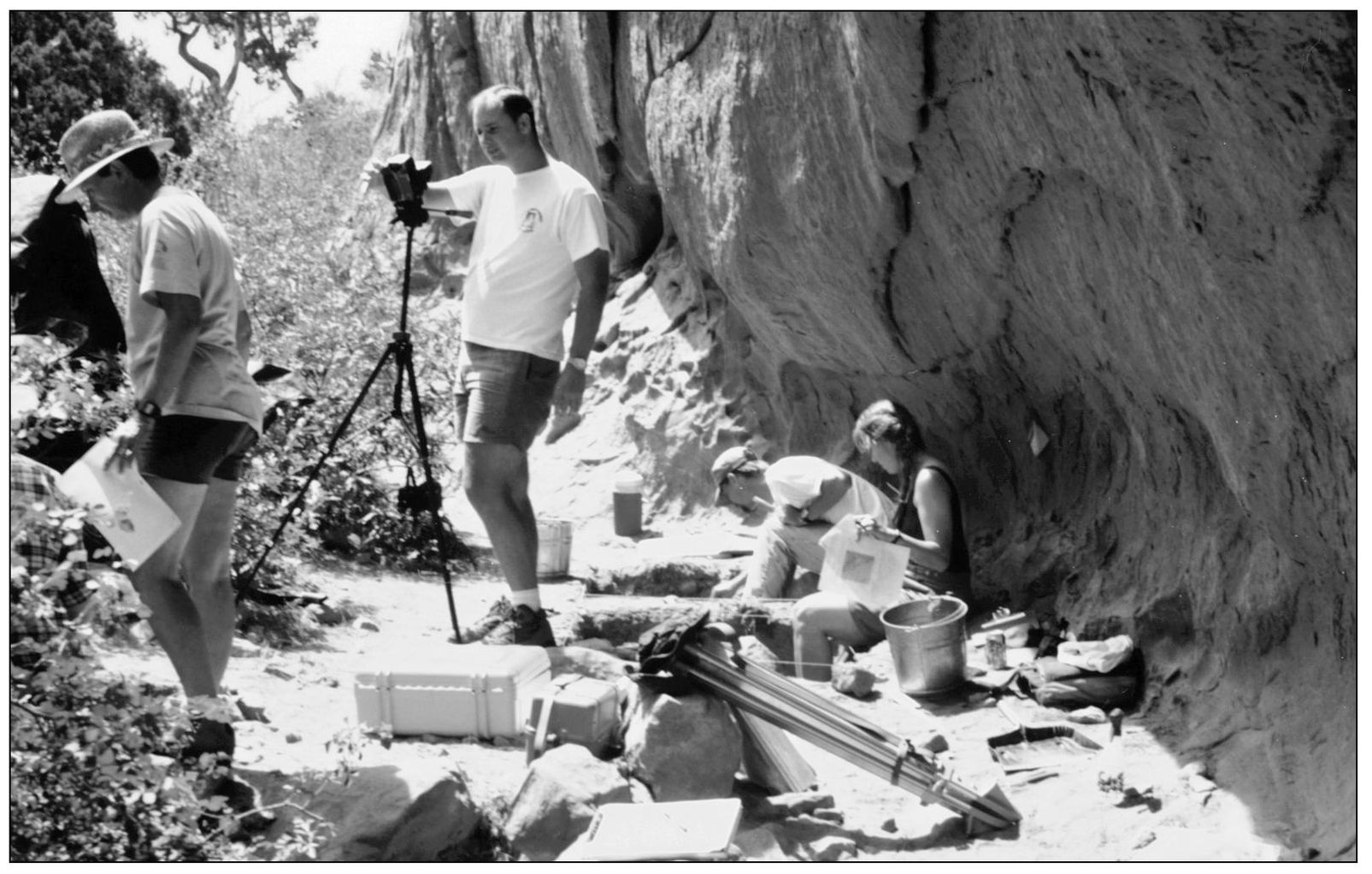

Prehistoric people probably related to the numinous landscape at Garden of the Gods much as American Indians do. This rock shelter, which would have provided a convenient place to camp for the night, was used from about 6000 BCE to around 1800 CE. (Courtesy University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.)

Ute Indians likely cooked their game in this fire pit at Garden of the Gods. Archaeologists date it to approximately 500 CE. Utes referred to the rock features at Red Rock Open Space and Garden of the Gods as the bones of Mother Earth. (Courtesy University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.)

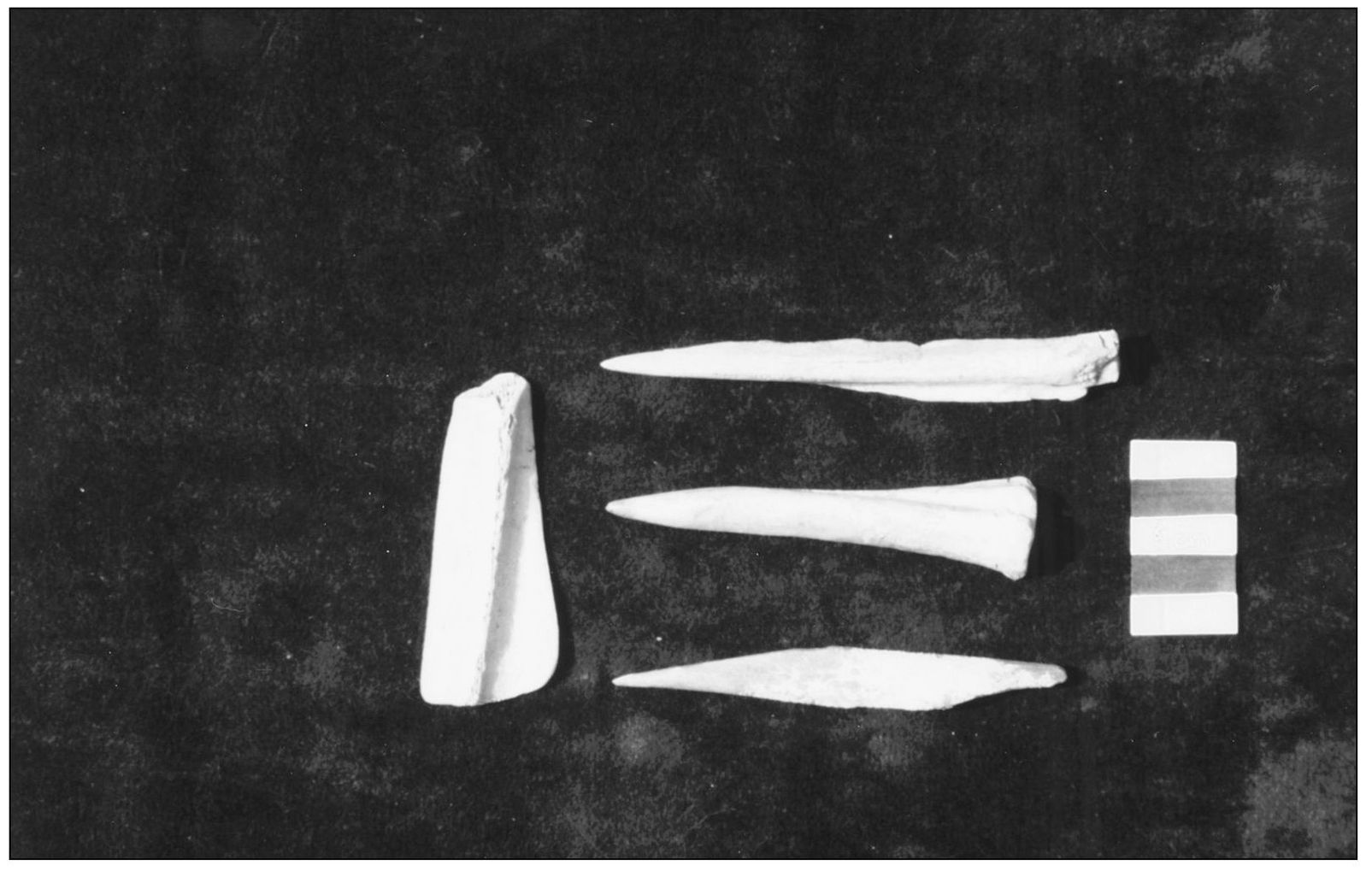

These bone tools, dated to about 790 CE, were found in a burial near the heart of Colorado Springs. Scientists associate them with the Plains Woodland culture. These people generally left few clues to their identity, as their structures were highly perishable. (Courtesy University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.)