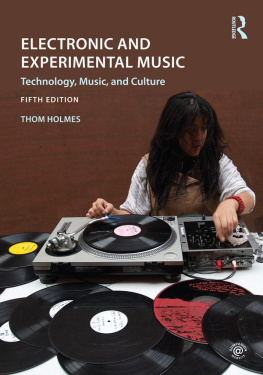

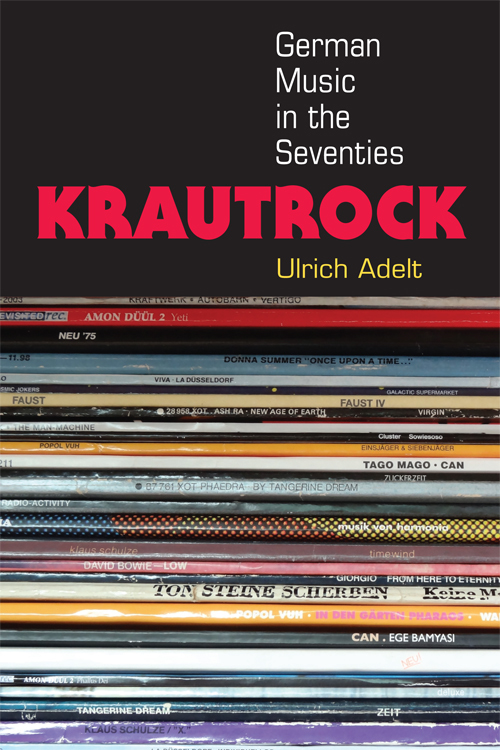

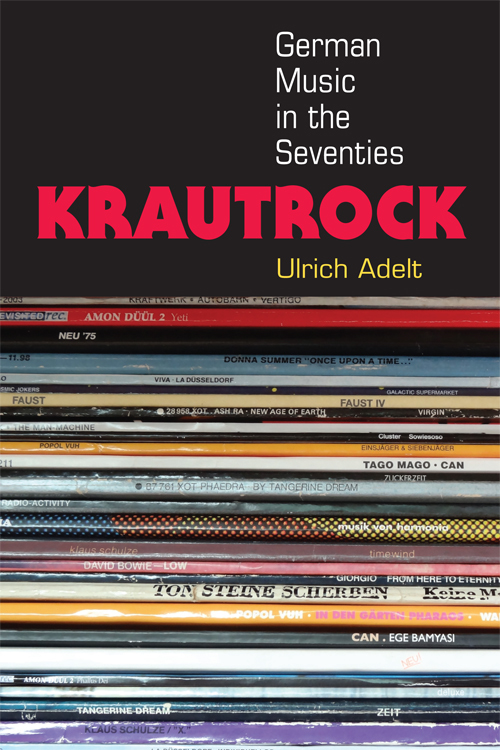

Krautrock

Krautrock

German Music in the Seventies

Ulrich Adelt

University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor

Copyright 2016 by Ulrich Adelt

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Adelt, Ulrich, 1972 author.

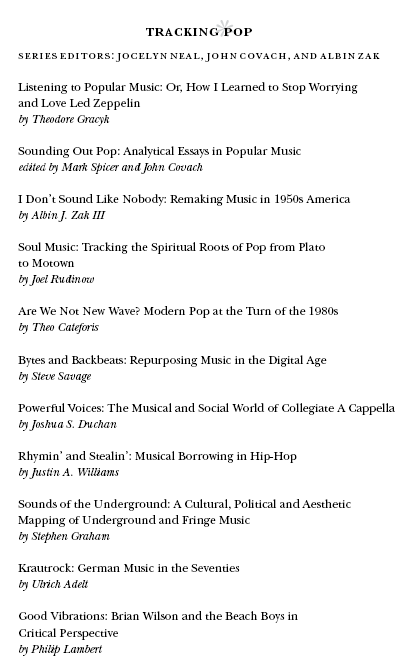

Title: Krautrock : German music in the seventies / Ulrich Adelt.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016. | Series: Tracking pop | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016006365| ISBN 9780472073191 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472053193 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122219 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Krautrock (Music)History and criticism. | Rock musicGermany (West)19711980History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3534.6.G3 A34 2016 | DDC 781.660943/09047dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016006365

First, I want to thank Hrfu Allstars (Hanno Kiehl, Dirk Reimers, and Sascha Krck), my on-and-off band for many years. We were making krautrock and didnt even know it.

I am extremely grateful for the unique and friendly environment in the American Studies program at the University of Wyoming. I especially want to thank Eric Sandeen and Frieda Knobloch, the two directors in recent years. Other Wyoming faculty that have greatly helped me with this book include John Dorst, Isadora Helfgott, Gregg Cawley, and Kerry Pimblott. Of course I cannot leave out our wonderful office assistant, Sophie Beck. I have also had many hardworking graduate assistants at Wyoming, so thank you, Glen Carpenter, Julian Saporiti, Robin Posniak, Rie Misaizu, Jascha Herdt, Kiah Karlsson, David Loeffler, Maggie Mullen, and Susan Clements.

In preparation for this book, I was able to spend a research semester in Germany, and I would like to thank the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), Sabine Broeck from the University of Bremen, and Ulrich Duve of the Klaus Kuhnke Archiv fr Populre Musik.

Thanks to everybody at the University of Michigan Press, especially Chris Hebert and the anonymous reviewers. Im also grateful to Joel Rudinow for recommending the press.

For answering questions about my research, I want to thank Jean-Herv Pron and Zappi Diermaier of Faust, Giorgio Moroder, Rusty Egan, Rudi Esch, and the Pitchfork writers Brian Howe, Dominique Leon, Nick Neyland, Brent Sirota, Nick Sylvester, Joe Tangari, and Douglas Wolk. For inviting me to talk about my research in Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, I want to thank Uwe Schtte, Hans Bak, Frank Mehring, and Barry Shank.

And finally, thanks to God and my wonderful family, without whom I would be nothing: my wife Ursula and my children Maya, Luna, Stella, and Noah.

Contents

West German popular music from the late 1960s and early 1970s, commonly referred to as krautrock today, has had an astonishing renaissance in the last decade. Reissues of long out-of-print albums, eagerly anticipated live appearances by formerly obscure artists like Faust, and the ongoing references to bands like Kraftwerk, Can, and Neu! in the music of post-rock, indie, and electronica artists have prompted a renewed interest in musicians who deliberately operated outside the Anglo-American mainstream. However, this book is not an attempt to celebrate the essential Germanness of artists like Klaus Schulze or Amon Dl II. Instead, I investigate how national identity gets transformed when it has become impossible to defend (as in the case of post-Nazi Germany). As I argue throughout the book, krautrock represents a process in which the nation-state becomes deterritorialized, hybridized, and ironically inverted, as well as increasingly cosmopolitan, communal, and imbued with alternative spiritualities.

I situate krautrock within its particular context of national identity and globalization and address krautrocks intersections of transnational musical production and the reshaping of the globalization of US popular culture within this framework. Although it emerged with an emphasis on a specific white West German counterculture, krautrocks expressions of sonic identity proved to be varied and conflicted. The transnational focus of my analysis within the context of globalization demands a broader definition of the term krautrock that is inclusive of developments on the periphery of any German mainstream, in particular in terms of gender, race, and nationality. Therefore, unlike other accounts of the music, this book prominently features artists like Donna Summer and David Bowie.

Generally, krautrock is used as a catch-all term for the music of various white West German rock groups of the 1970s that blended influences of African American and Anglo-American music with the experimental and electronic music of European composers. Many krautrock bands arose out of the West German student counterculture and connected leftist political activism with experimental rock music and, later, electronic sounds. There are no precise dates for krautrock, and while the heyday of the movement was roughly from 1968 to 1974, one could also argue that it lasted well into the 1980s. Krautrock was primarily a West German art form and differed significantly from East German Ostrock, with the latters emphasis on more traditional song structures. Krautrock and its offshoots have had a tremendous impact on musical production and reception in Great Britain and the United States since the 1970s. Genres such as indie, post-rock, techno, and hip-hop have drawn heavily on krautrock and have connected a music that initially disavowed its European American and African American origins with the lived experience of whites and blacks in the United States and Europe. At the same time, while reaching for an imagined cosmic community, krautrock, not only by its name, stirs up essentialist notions of national identity and citizenship.

Despite being frequently mentioned in magazines and on Internet blogs, krautrock continues to be a much-understudied topic among popular music scholars (a notable exception is a special issue of Popular Music and Society from December 2009). Apart from a few publications that merely list individual performers and bands, the only books about the topic available in English are David Stubbss journalistic overview Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany (2014) and Nikos Kotsopouloss coffee-table tome Krautrock: Cosmic Rock and Its Legacy (2010).

Krautrock and Spatiality

I hesitate to call krautrock a genre or movement and would rather describe it as a discursive formation or a field of cultural production. According to Michel Foucault, the unity of a discourse is based not so much on the permanence and uniqueness of an object as on the space in which various objects emerge and are continuously transformed.

Rather than providing a purely musicological or historical account, I discuss krautrock as being constructed through performance, articulated through various forms of expressive culture (among them, communal living, spirituality, visual elements but, most importantly, sound) by people not even directly interacting with each other but still structurally related. This explains how krautrock succeeded through time and space and does not merely reflect historical events. Barry Shank has recently addressed the complex and dynamic relationship between music and identity in which real politics can emerge: The act of musical listening enables us to confront complex and mobile structures of impermanent relationshipsthe sonic interweaving of tones and beats, upper harmonics, and contrasting timbresthat model the While Shanks examples are mostly Anglo-American, krautrock serves to illustrate the transnational dimension of the politics he so aptly describes.

Next page