In September 2000 it was my honour to give the Liam Lynch oration in Fermoy, Co. Cork. General Lynch was a War of Independence and Republican Civil War General who was shot at the age of twenty-nine . My father, at the conclusion of the War of Independence, was just twenty-three. He was born in 1901. In Dublin Made Me he sets out in proud detail his involvement with Liam Lynch, for whom he acted as Adjutant.

As a family, we were very proud of our father but did not realize until early adulthood his immense contribution to the foundation of the twenty-six-county Republic and his subsequent involvement in many historic landmarks along the way of his career up to his retirement . He was over seventy when he wrote his two books, Dublin Made Me and Man of No Property. It is difficult to chose between the two, but I did always feel an affection for his first book. It was closer to my childhood and young manhood perception of my father than his later book. Its spirit touches me more.

In our very early years the names of Aiken, Lemass and de Valera were part of our lives. Frank Aiken was a frequent visitor to our home. Eamon de Valera and Sean T. OKelly were also visitors to Dundrum. The place was sometimes like an anteroom to a Fianna Fil Ard Fheis!

My mother, Mary Coyle, had a spell in Kilmainham during the Civil War for her troubles and was a very good foil for my father. As Todd was tough-minded, Mary was gentle. It was a good balance and it worked. If not a liberal, she was very liberated in her views.

Both Dublin Made Me and Man of No Property were produced from memory, with the enormous help of my stepmother, Joyce Duffy. Our family owes her much. My fathers memory was assisted by input from a very few close associates. It was some achievement. It is a pity that more of his generation didnt add their voices to the airwaves and their memories to paper.

Todd Andrews in his professional life may have been perceived as a hard man and indeed he may have been such but his integrity and honesty shone through his various careers: Bord na Mona, Coras Iompair ireann and Radio Telefis ireann. His real monument is Bord na Mona. Many jobs were created and many homes built in the midlands on the back of harvesting of turf and the making of peat briquettes. Mr Aiken and Mr Lemass were the visionaries on turf, but without my father the project would not have happened. His enthusiasm , energy and leadership were the real essence of the success of the development of our bogs.

Never a glad-hander, he despised subterfuge and graft. His door was always open to an old comrade from whichever side of the split. His regard for Michael Collins was genuine and deep and it was this respect that left his heart, if not his mind, open to the other side from the Civil War tragedy.

This book will remain forever a good and relevant record of my father and his times, and of his great contemporaries.

Preface and Acknowledgments

This is an account of my childhood, boyhood and early manhood as recollected by me in my seventies.

It has been written largely, though not wholly, from memory. I am aware of the fallibility of memory. I am particularly aware of that phenomenon of memory known to psychologists as paramnesia, where events as they really occurred are distorted, telescoped, transposed or otherwise confused. Hence I disclaim any intention of writing a historical account of these years, even of the public events from 1917 until 1923 in which I played a most minor of minor roles.

Writing in my old age of the happenings of my early years I am conscious that my reactions to these happenings were based mainly on emotionalism and enthusiasm. I rarely thought; I felt. But I am not too critical of what I felt or did. Most of my feelings seem to me in my maturity to have been justified by events.

Despite the tribulations which affected the nation over the years, especially in the years of my youth, I reckon myself lucky to have been one of that fortunate generation which lived to see Irishmen in control of the greater part of the country.

I wish to thank my wife, Joyce, for her encouragement to me to persist with this book when so often I felt like abandoning it. She typed my manuscript, inserting verbs which I had omitted and limiting my colloquialisms.

I am particularly indebted to my old friend and former colleague C.B. Murphy for having devoted so much time and energy to reading the typescript and for making so many suggestions, principally aimed at eliminating the repetitiousness which, in writing and conversation, afflicts old age. I am most grateful to him.

I am grateful, too, to Dr Brian Inglis for his kindness to me when I was writing the book.

I wish to acknowledge to Mr Alf MacLochlainn, Director of the National Library, for the help he so readily gave me whenever I requested it.

Childhood

I n 1901 the year I was born Queen Victoria died to be succeeded by Edward VII, called the Peacemaker. The Boer War was still in progress although no one realized that it was a cloud no bigger than a mans hand presaging the destruction of the British Empire.

Ireland was at peace. The Nationalist Parliamentary Party under the leadership of John Redmond was slowly beginning to recover from the blight of the Parnell split. Arthur Griffith, founder of Sinn Fin, was a voice crying in the wilderness of national apathy. He had not yet written The Resurrection of Hungary. The injection of national spirit from the Gaelic League and the Irish Literary Revival had, as yet, little effect in restoring national pride.

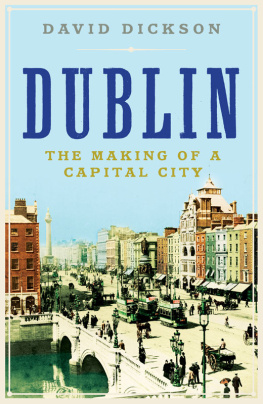

Dublin still retained the beautiful buildings, monuments, parks, streets and squares which it had inherited from the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. But it had lost the consciousness of a separate identity which, despite their intense loyalty to the Crown, had been characteristic of the Anglo-Irish.

Dublin was a British city and accepted itself as one. Its way of life, its standard of values, its customs were identical with those of, say, Birmingham or Manchester except to the extent that they were modified by one great difference: religion. In Dublin at the turn of the century the population was divided into two classes: the rulers and the ruled. The rulers were mainly Protestants, the Catholics the ruled. The Catholics at whatever income level they had attained were second-class citizens.

From childhood I was aware that there were two separate and immiscible kinds of citizens: the Catholics, of whom I was one, and the Protestants, who were as remote and different from us as if they had been blacks and we whites. We were not acquainted with Protestants but we knew that they were there a hostile element in the community, vaguely menacing us with such horrors as Mrs Smylies homes for orphans where children might be brought and turned into Protestants. We Catholics varied socially among ourselves but we all had the common bond, whatever our economic condition, of being second-class citizens.

At the top of the Catholic heap in terms of worldly goods and social status were the medical specialists, fashionable dentists, barristers , solicitors, wholesale tea and wine merchants, owners of large drapery stores and a very few owners or directors of large business firms. These were the Catholic upper middle class; they were the Castle Catholics (the Castle being the seat of Government). Their accents were undistinguishable from those of the Dublin Protestants , who held the flattering belief that they spoke the best English in the world. The Castle Catholics played golf, rugby, cricket, tennis, hockey and croquet and dressed as these games required. They lived cheek by jowl with the Protestants on Mountjoy Square, Fitzwilliam Square and Merrion Square or in Foxrock, Dalkey or Kingstown. They owned carriages and were among the first to own motor cars. The Churchs ban on Catholics attending Trinity College did not prevent them from sending their brighter children there. They entertained one another and any Protestant who would accept their invitations. They had dinner in the evening, and dressed for it. They had many servants: butlers, housekeepers, cooks, housemaids, tweenies, nannies and coachmen. They sent their sons to the English Catholic public schools at Ampleforth, Stonyhurst and Downside or, as a compromise, to Clongowes which was the top Jesuit school in Ireland. Their daughters went to school to the Sacred Heart Nuns at Mount Anville and were finished at Vienna and Dusseldorf. For their spiritual needs, they preferred the urbane ministrations of the Jesuits to the cruder rituals of the parochial clergy or the unsophisticated pieties of the Franciscans . An invitation to a garden party at the Viceregal Lodge or to a reception at Dublin Castle was the realization of their social ambitions . From time to time they received knighthoods or judgeships, but even such hallmarks of gentility did not equate them with the top Protestants, who regarded them as Uncle Toms. The Castle Catholics had annual holidays at Brighton or Bournemouth. In politics they supported the union with Britain. To most of their fellow Catholics they were John Mitchels genteel dastards and were detribalized.