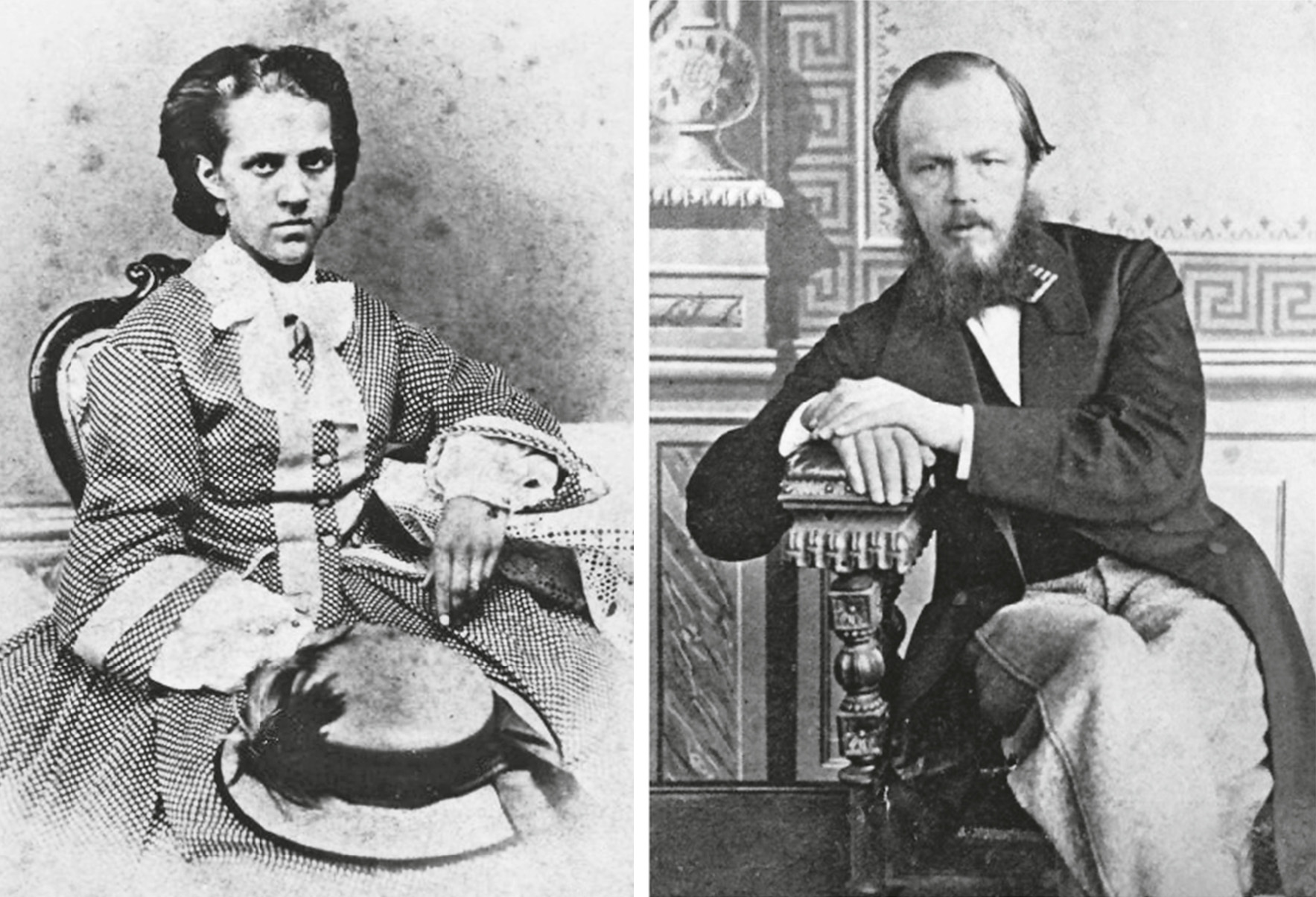

left: Anna Snitkina. right: Fyodor Dostoyevsky, early 1860s.

Introduction

On the cold, clear morning of October 4, 1866, a slender twenty-year-old stenography student in a black cotton dress left her mothers apartment in Petersburg. A short distance away, she stopped by Gostiny Dvor, a huge arcade of shops on Nevsky Prospect, to buy some extra pencils and a leather portfolio, hoping to lend a more businesslike air to her youthful appearance. Half an hour later, arriving at a gray-bricked building on the corner of Malaya Meshchanskaya Ulitsa and Stolyarny Pereulok, she ascended the poorly lit staircase to the second floor and rang the doorbell to Apartment 13, where her prospective employer was expecting her. The students name was Anna Snitkina, and her employer-to-be was a forty-four-year-old former convict and enigmatic widower about town who also happened to be a novelist of some fame: Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Anna looked at her watch and smiled to herself. It was a few minutes before eleven thirty, just as she had been instructed. A prudent young woman, she was not about to take any chancesnot on the day she hoped to be hired for her first job.

Almost immediately, a thickset woman in a green checkered shawl opened the door. Having followed the serialized installments of Dostoyevskys newest work, Crime and Punishment, Anna wondered whether this very garment might be the prototype of the worsted shawl that played such an important role in the novels Marmeladov family. She did not dare ask, of course, and told the maid simply that she had been referred by her stenography instructor, Professor Olkhin, and that the master of the house was expecting her.

The maid, whose name was Fedosya, led Anna down the dark corridor into a dining room, its walls lined with a chest of drawers and two large trunks, all of them draped in intricately crocheted rugs. She asked the young guest to have a seat and said her master would come shortly.

Two minutes later, Dostoyevsky appeared. Without so much as a greeting, he commanded Anna to go to his study while he fetched tea. And then he was gone again.

Anna looked around as she entered the large, gloomy study. Its divan was draped in shabby brown fabric; nearby, a small round cloth-covered table was shared by a lamp and two or three photo albums. Two windows let in a few rays of sunlight.

It was dim and hushed, she later recalled, and in the dimness and silence you felt a kind of depression. It was the sort of study she would have expected to find in the home of someone of modest means, not a man rapidly becoming one of Russias most important authors. She scanned the room for clues about her potential employerlistening in vain for childrens voices, wondering whether the painting above the sofa, of a cadaverous woman wearing a black dress and cap, was a portrait of Dostoyevskys wife, who had died two years earlier. (It was, Anna would later learn.)

A few minutes later, the enigmatic fellow shed encountered earlier reappeared. Anna tried hard to project confidence; this was a moment she had been anticipating longer than she might have cared to admit.

The name Dostoyevsky had long been familiar in the Snitkin home. He was her fathers favorite writer; whenever the subject of modern literature arose, he would inevitably say, Well now, what kind of writers do we have nowadays? In my time we had Pushkin, Gogol, Zhukovsky. And of the younger writers there was the novelist Dostoyevsky, the author of Poor Folk. That was a genuine talent. The past tense was no mistake: Unfortunately, he continued, the man got mixed up in politics, landed in Siberia, and vanished there without a trace. Then, in 1859, to the delighted surprise of Annas father, Dostoyevsky had returned to the capitalafter a four-year prison sentence in Siberia followed by five more years of mandatory military serviceand resumed his writing with newfound vigor. Annas father was a devoted reader of Time, a journal founded by Dostoyevsky and his brother Mikhail, and before too long the whole Snitkin family was reading Dostoyevskythough none of them with greater emotional investment than Anna.

The work of Dostoyevsky was well-known among educated readers like Grigory Ivanovich Snitkin, who subscribed to Time and the other thick journals, as they were known. Published weekly or biweekly, these compendia of literary, philosophical, and journalistic material were nineteenth-century Russias equivalent of The New Yorker, Newsweek, and Scientific American all rolled into one. They included news, book reviews, cultural and literary criticism, scientific articles, and, of course, fiction; in fact, nearly every Russian novelist of the time debuted in these journals. Dostoyevskys own first original published work, Poor Folk, appeared when he was twenty-four, in 1846the year Anna Snitkina was born.

An epistolary novel, Poor Folk traced the love affair between an impoverished forty-seven-year-old copy clerk and his distant relative, a poor orphan girl. Readers recognized the novel as an original and moving take on the social Christianity and sentimental philanthropism that were characteristic of literature of the time. A new Gogol has arisen! exclaimed Vissarion Belinsky, the eras most influential literary critic, after reading it. Do you yourself understand what you have written? he asked the starstruck writer when they met in persona day Dostoyevsky would long remember. Belinskys endorsement gained Dostoyevsky immediate entre into elite literary circles, and the novel was a great success with the reading public as well.