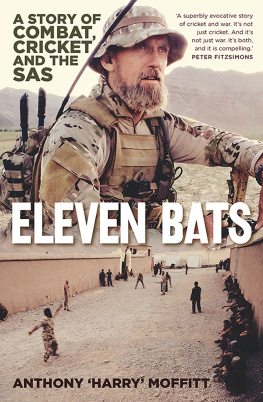

Three minutes! yelled the door gunner of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk as he racked his dual M60 machine guns. The Black Hawk was flying low and fast, straight up the middle of the Khod Valley. I looked down onto the valley floor, the scene of many events in my life over the previous eleven years. Cricket games and practice, contacts and conversations with the enemy, night-time motorbike operations, and long-range vehicle patrol quizzes. This was my last time. I looked at one of the junior operators, Jumbuck, who had his eyes closed, relaxed and deep breathing. He wasnt scared, he just knew he needed plenty of oxygen in his brain to optimise his decision-making once we hit the ground. Everyone was box breathing, and I joined them.

One minute!

The doors opened and slid rearwards. I stuck my head out and looked ahead to try to see the village, our destination. I remembered how its early-morning call to prayer gave me an unexpected sense of peace back in 2005.

Thirty seconds!

The Black Hawk banked over the small group of compounds we were targeting and the scout pointed with his gun to several fighting-age males running into a creek line. One of them was armed. We released our strops and gave each other one last glance.

Before the pilot had a chance to touch down and the loadmaster give us the chop, the whole team left the bird and sprinted towards the enemy. I was running again, the hot dusty air burning my lungs. This was probably the last time I would run like this in my life. I could barely keep up with Jumbuck, who, mid-sprint, stopped, sucked in a quick deep breath, and released three rounds before sprinting off again. I battled on in pursuit.

Jumbuck had shot and killed someone who turned out to be a senior Taliban commander. The shot was amazing, the best I had ever seen: around 200 metres, with his heart pounding and breathing rate through the roof, standing unsupported, aiming at a moving target. Surgical. The new breed of operators were, at the end of the war, elite clinical machines.

By the time all the teams had got onto the ground, our team had found ourselves in a creek line guarding ten suspects we had gathered while exchanging sporadic fire with enemy who were concealed in the cluster of compounds. All of a sudden, an armed bad guy ran obliquely across our front from right to left. He was shot and killed instantly. He fell into an open patch of tilled dirt. I looked around for a better position, across the creek line on some more secure-looking higher ground. But when we moved, rounds cracked into the banks of earth around us, forcing Stuey Two-Up and the team back into the low ground. I thought this was a tactically unsound position. I could smell the enemy body, which had already started to decay in the heat. The situation felt bad. I had a sense that the enemy were reorganising to attack.

Just then, a boy of about fourteen and an old man who could have been his grandfather wandered out of some reeds further up the creek. The old man had a bleeding forearm, and the boy had a severe wound to his head and stumbled along, semiconscious, bleeding badly. His skull was open and his brain appeared to have been compromised. Under fire, our medic, Cuddles, ran out, grabbed the boy and went to work.

How is he, Cuddles? I asked.

I think I see brain, and hes bleeding pretty heavily. We need to get him out of here.

Fuck, if we call in a bird theyll be a sitting duck. I think the enemy are reorganising and setting up to attack.

The way forward was clear. Mission came first, and protection of the force a very close second. No civilian should trump either, and neither should I be contemplating exposing an Air Medical Evacuation team and helicopter. Or should I? What the fuck was I here to do? Protect the locals and make it safe for them to carry on their lives.

I got on the radio to Pup.

Have a Pri 1 civcas, request approval to AME.

This brought down a backlash from some in the troop, who disagreed with putting air assets and others in danger for an Afghan civilian.

Fuck em, Harry, someone said. Were in the middle of a gunfight. Let him go and lets get to a more secure position.

I ignored the free advice and radioed HQ. I told them the situation, including the threat profile. The AME were happy to react and be updated once they were closer to the target. I had never really had a moral dilemma such as this. Put four helicopter operators and maybe a couple of SAS operators at risk for a civilian boy? It wasnt our job. But if protecting the Afghan population wasnt our job, what were we doing? Was it all about chasing bad guys? There were fucking bad guys everywhere. Where did it end? I decided that letting the boy die was not something I was willing to live with. I had to draw a line, and this was it.

Stuey Two-Up came over as I was finalising the details for the pick-up.

Fuck, Harry, what are you doing, mate? We have a situation here, they look like they are re-orging.

Mate, we are getting him out of here. We cant save or kill everyone, but Im fucked if we arent gunna give this little bloke a good chance. If we dont, then we might as well pack up and go home.

After that last gig, the team arrived in Perth quietly on a private flight before going into a hangar for our quarantine checks. Then we were put onto a bus with the curtains drawn. No crowds, no fanfare, no cameras, no cakes, no family. As we drove back to the serenity of Swanbourne, I looked out of the window at life going on in Perth, civilians blissfully unaware of the death, destruction and darkness we were returning from. I wondered if, had they known, they would have cared.

I reckon youre getting a bit old for all this, eh Harry? Stuey brought me out of my nostalgia. You looked a bit slow on that last gig. The pack looked a bit heavy?

Stu, I was humping packs in Baghdad while you were still in Dads bag.

The boys all laughed, and although Stuey was speaking tongue in cheek, he was right. I was too old for this.

It had been a long journey, but what sticks with me most is not the memory of confrontation but the humanity, humour and psychology of modern combat. I had listened intently to the veterans in the World at War television series early in my life, when they reminded us over and over again of the horrors and depravity of war. I was inspired from afar by their words about mates, family, and a sense of humour. Id been inspired, from afar, by people like David Stirling, Albert Jacka VC, Percy Cerutty, and the white mouse Nancy Wake among others. But I was forged by men I worked alongside, like Rowdy Joe, Seadog, Streaky Bacon, G-Port, Cranky Frank, Chief Siaosi, JJ, Hawkeye, and of course Big Duke. I liked to think that a little of their excellence had rubbed off on me. Even if it hadnt, I was much the better for having met them, as they had all helped mould the curious, compassionate, determined and disciplined humanitarian spirit that my mother had instilled in me.

As I stared out of the bus into the Perth afternoon, I thought about how Mum still lived in me. I still often heard her, clear as day. Through the noise of that last afternoon in combat, it was Mums voice that had told me I had to put that young Afghan boys life first.

At the end of my military days, I realise I will always live with mixed feelings. I am sad for all the death and destruction, the killing and suffering. I am disappointed by the way the unit seemed to have lost its way and the current investigations that have brought disrepute to our fine name and reputation. I am angry at politicians, high-ranking officers and businessmen who seem to use warfare as their plaything, to advance their careers, to feed their egos and to make money. I am confused and still picking over the ideology of it all. I feel disappointed and a little betrayed that the Taliban is coming back to power in Afghanistan, and embarrassed by our greedy and Machiavellian role in keeping Timor-Leste impoverished. However, I am immensely proud to have served in an amazing unit and community, to have been considered worthy of joining its number. I am extremely proud of how the unit has reacted to the recent challenges and those individuals who have fought and are fighting for its integrity. I am proud and thankful for the amazing soldiers and operators with whom I have served and become dear friends.

Next page