Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2021 by Charlie English

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R andom H ouse and the H ouse colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published in hardcover in the United Kingdom by William Collins, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, London.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: English, Charlie, author.

Title: The gallery of miracles and madness: insanity, modernism, and Hitlers war on art / Charlie English.

Description: New York: Random House, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020044464 (print) | LCCN 2020044465 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525512059 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525512066 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: National socialism and art. | Art and mental illnessGermanyHistory20th century. | Prinzhorn, Hans, 18861933Art collections. | Prinzhorn, Hans, 18861933. Bildnerei der Geisteskranken. ArtDestruction and pillageGermanyHistory20th century. | Killing of the mentally illGermanyHistory20th century.

Classification: LCCN 6868.5.N37 E54 2021 (print) | LCCN 6868.5.N37 (ebook) | DDC 700.94309043dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020044464

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020044465

Ebook ISBN9780525512066

Maps by Mapping Specialists Limited

randomhousebooks.com

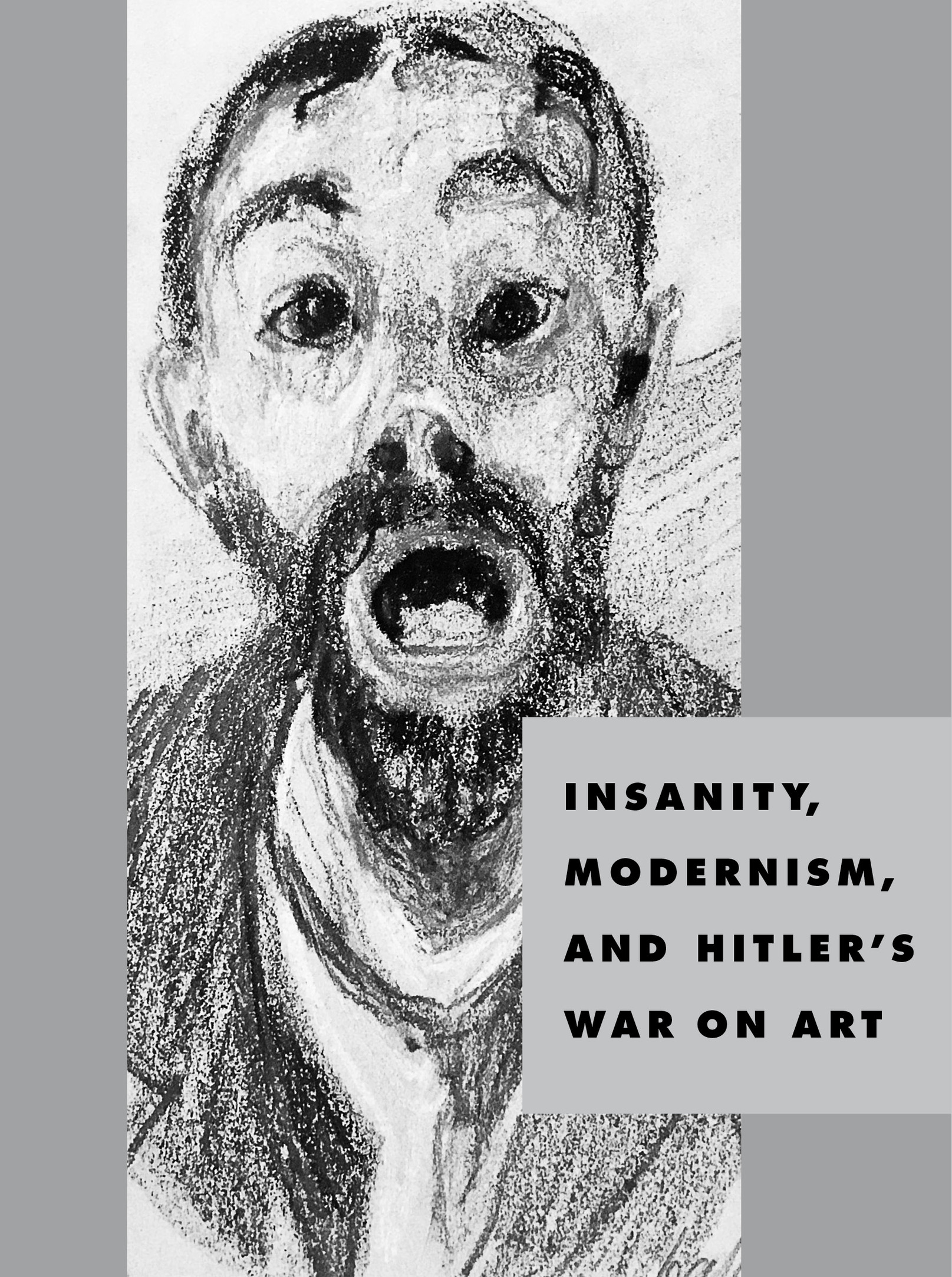

Title-page art by Franz Karl Bhler, Das Selbst, 1919. Prinzhorn Collection, University Hospital Heidelberg, Inv. No. 3018

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Alex Merto

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

Contents

PRINCIPAL ARTISTS

Franz Karl Bhler

Else Blankenhorn

Karl Genzel

August Natterer

Hyazinth von Wieser

Paul Goesch

Carl Lange

Katharina Detzel

Joseph Schneller

Gustav Sievers

Agnes Richter

August Klett

Frau von Zinowiew

Josef Forster

Wilhelm Werner

PREFACE

A LETTER FROM BERLIN

On October 9, 1939, when the Second World War was barely a month old, the German Ministry of the Interior issued a directive to mental health institutions throughout the Reich, signed on behalf of Berlins top medical official, Dr. Leonardo Conti. As part of new wartime economic measures, Conti required asylum doctors to register every patient in their care who suffered from certain psychiatric illnesses, including schizophrenia, epilepsy, senile dementia, syphilis, feeblemindedness, encephalitis, and Huntingtons disease. They were also to register anyone without these conditions who had spent five years or more in an institution, or who was classed as criminally insane, or who did not possess either German nationality or German or related blood. In unclear cases, medical staff were to err on the side of registration, since it would be better for Berlin to have too many rather than too few patients on its lists.

Contis letter was followed by registration forms: one copy was to be filled out for each patient. Besides logging their racial category (picking from a menu that included Jew, Jewish half-breed, first or second degree, Negro, Negro mongrel, Gypsy, and Gypsy mongrel), doctors were to provide details of each individuals ability to work, the nature of his or her illness, and whether they received visitors and how often. The forms had to be completed by typewriter where possible and returned to Berlin within a tight deadline.

As the directive landed in psychiatric institutions across the country, medical staff tried to guess at what it meant. Was the government going to relocate these patients? If so, to where? Were they looking for laborers to dig trenches at the front, or trying to free up beds for wounded soldiers? The registration form itself was scoured for clues. As the bureaucrats hadnt left much room for a detailed medical opinion, at least one doctor concluded that it couldnt signify anything too drastic. Others found the question about visitors highly suspicious. Why would Berlin need to know that?

The secret purpose of the Conti letter would unfold over the following weeks. Once the paperwork was returned, it was copied and sent out to a panel of psychiatrists, all ardent National Socialists, who were instructed to mark each case in pencil with a red + or a blue . The few patients who received a blue minus sign were left alone. The red + was a death sentence. These people would be collected from their clinics and asylums in groups, loaded onto buses, and taken to specially converted nursing homes, where they were undressed, weighed, and pushed into airtight chambers, which were then flooded with lethal carbon monoxide. When they were all dead, their corpses were burned and their ashes dumped on the fields. Aktion T4, as this program was known, represented the first time a government had organized the industrialized extermination of a section of its population. For the Nazis, it would serve as the prototype for the greater mass murder to come.

Among the hundreds of thousands of mentally ill and disabled people killed in the so-called euthanasia actions were two dozen whose artwork had been collected by the psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn in the aftermath of the First World War. The way in which these artist-patients found themselves on a collision course with the Nazi government is the story Ive tried to tell in this book

Exploring art in the context of National Socialism may seem counterintuitive, even distasteful. What relevance can painting or sculpture have when measured against so many deaths? Arent Hitlers ideas about culture a distraction from his far more pressing crimes, to which so many words have already been devoted? In fact, the following narrative shows that the opposite is true. Hitlers mass murder programs and his views on art were intimately connected through a network of pseudoscientific theories about race, modernism, the concept of degeneracy, and the people he deemed to be lebensunwertes Leben, life unworthy of life.

The art collection Hans Prinzhorn gathered at Heidelberg consists exclusively of work by the inpatients of mental hospitals. Though at one time it was envisaged as a research archive for the University of Heidelberg Psychiatric Clinic, Prinzhorn soon became far more interested in its artistic value than in its potential to help diagnose mental illness. This was in large part due to the extraordinary qualities of the material he discovered.

The men and women who created these works spent their lives cut off from the outside world, often forgotten by their peers and even by their families. Diagnosed mostly with schizophrenia, they didnt always intend to make art. They used sketches, sculpture, and writing to chart aspects of their psychotic reality, or to communicate messages from an isolated interior. The collection includes all kinds of products, from paintings, drawings, and collages to doodles, poems, and music, executed on or with whatever came to hand: discarded nursing rosters, menus, sugar bags, used envelopes, even toilet tissue. Sculptures sit alongside designs for great inventions, diaries, and lettersnone of which seems to have ever been sent. One woman repeated the same penciled phraseSweetheart comeon hundreds of sheets of paper, until each was dark with longing. Some drew pornography. Others worked with needle and thread, creating stuffed mannequins or embroidering clothing with words and phrases that they wore next to the skin. Viewing this often strange material is a moving and sometimes transcendent experience. Visitors remark that its as if it bubbled up from the depths of the human psyche or opened windows on a different reality. One former curator compared her encounter with the collection to the moment a dam bursts: Remarkable worlds opened up before me, she wrote, drew me into their power; open spaces took away my equilibrium and made me dizzy.