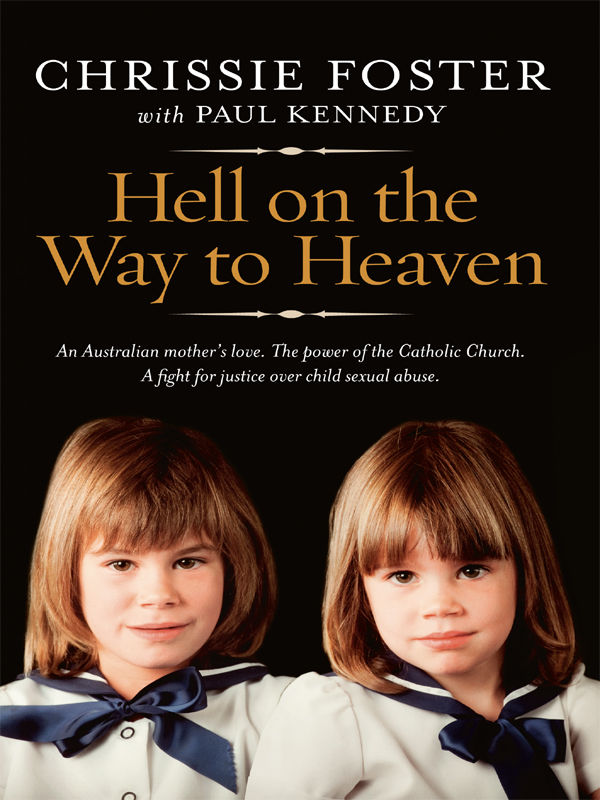

Prologue

Saturday 19 October 1996

Melbourne, Australia

Attending Archbishop George Pells Melbourne Forum, a response to the Catholic Churchs Sex Abuse Crisis

My voice embarrassed me.

It fell apart whenever I was stressed or nervous. The words formed perfectly in my mind. They were strong invincible words, of forceful sentences, containing the irrefutable truth. But when it came time to speak, they broke and stumbled from my mouth, cracked, high-pitched and shaking. This angered me, although not nearly as much as the other injustices in my life.

In the mid-1990s, when I was starting my unholy battle against the Catholic Church, I recorded a message of anguish, pouring my feelings out into a sound room microphone and recorder, to be played at a historic forum of victims of clergy sexual abuse, before their families, friends and leaders of the Church. I wondered how my croaky voice would sound broadcast to a packed hall, boomed above the quiet tension by public address speakers.

I chose with great care what I wanted to say.

It used to be that I read the Bible every day

Would my many years of Christian devotion make the Church representatives take me seriously?

People are dying

Would they believe me?

We have been so deeply betrayed.

Would my voice humiliate me? Or worse? Would it be so weak that the Church would not hear me at all? I was about to find out.

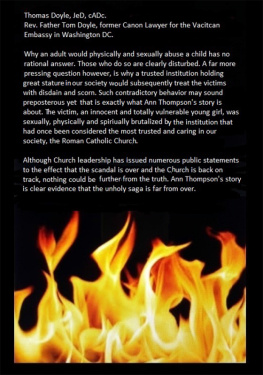

The church was insisting it was not in crisis. But in the four years between 1992 and 1996, thirty-two Australian paedophile priests and brothers had been arrested, charged and had pleaded guilty, or were found guilty in court, of sexual assaults. Twenty-two of them had been jailed for their criminal assaults. This alone was scandalous. But it was just the beginning. There were so many more to be uncovered and prosecuted. The hierarchy had a reasonable understanding of the potential scale of the problem because it had taken out a multi-million-dollar insurance policy against victims claims. It must have felt vulnerable. The Churchs actions in moving offenders from parish to parish, hiding their crimes, denying paedophilia existed and refusing to be accountable were being heavily scrutinised by the media. The forum we were here to attend would, by any definition, be best described as a crisis meeting even if the hosts did not use the C word.

We were seated inside the Catholic Church headquarters, east of the citys biggest buildings, a short stroll from one of the most majestic cathedrals in town, which overlooked the states Parliament House. Anthony, my husband, and my mother sat next to me. Beside and around us were my aunt, uncle and a number of friends from Oakleigh. Soon victims of sexual assault, their families and friends were filling up the rest of the seats, all facing the stage in anticipation. The atmosphere inside was subdued and solemn, as people sat alone in silence or in small groups, speaking quietly to each other. Each person or family had unique experiences and pain, but we all had the same secret hope that justice and understanding were only moments away.

I knew all of us would rather not have been there, would prefer our loved ones were as they should have been, without the suffering. The unholy hand of paedophilia and sexual assault within the Church had touched all three hundred and fifty members of the audience. The man who was hosting the forum, George Pell, the new Archbishop of Melbourne, entered the room. Our eyes followed him and he was accompanied by a foreboding silence as he took his seat on the stage, looking down on us.

We had a full arsenal of questions. Had they finally heard us? Did they now care? Did they believe us? Were they going to open their hearts and minds to victims?

Chapter 1

My religious origins

Way off the western coast of Scotland, past the Inner Hebrides, past the Outer Hebrides, out in the Atlantic Ocean is a dot of an island called St Kilda, flanked by rock pinnacles, styled by the waves of centuries. The lonely archipelago, lashed by violent salt air, must be the windiest and most isolated place on earth that isnt made of ice. These days, lowlying quilt clouds and thousands of majestic seabirds are the cliffs only friends. But people used to live there. My ancestors.

I come from a long line of Scots on my fathers side. They were Presbyterians but this was never mentioned. In our life there were only Catholics or non-Catholics.

St Kilda wasnt named after a saint. Rather, it came from the word skildir, meaning shield, which is what the islands resembled to the Vikings on their ships.

The people of St Kilda lived in a simple but fascinating way, through a community of hardship. Sadly, only one in ten babies survived. It was traditional for an old woman to visit all newborn infants with a sheeps stomach-bag full of oil. The old woman would rub the babies cords with the special brew. It was a crude ritual. The bag and its oil contained tetanus and most newborns died of lockjaw within days. It was so common that the mothers carried tiny coffins with them when they went to give birth.

My family name on that side was MacQueen. I used to try to identify relatives in old photos, until I realised they were all relatives, not just those bearing the name MacQueen. The island men had red hair and all the women had black hair, just like mine.

In 1852, thirty-six of the one hundred and ten islanders sailed for Melbourne, Australia, accepting an offer from the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society. It was a disaster in more ways than one. The eight families who braved the voyage were the strongest and best the island had to offer. They were the vanguard. Others waved them goodbye and hoped to join them some day. But their departure tore apart and demoralised the close-knit community.