This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For Virginia Foisie Rusk

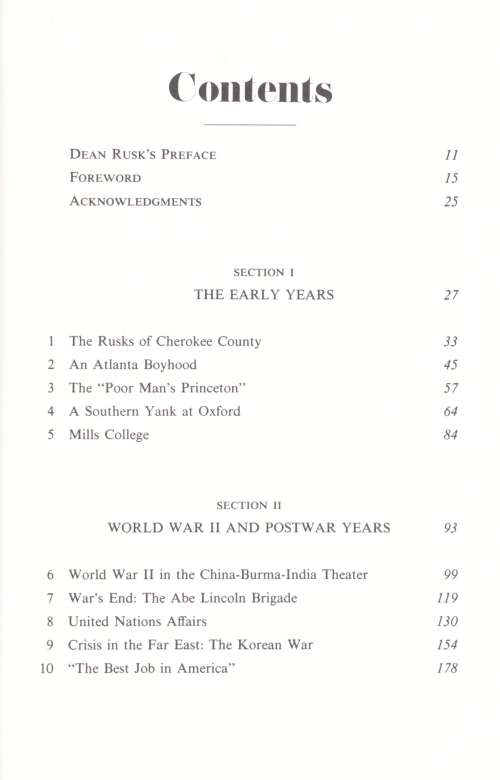

Doan I tusk's Profaoo

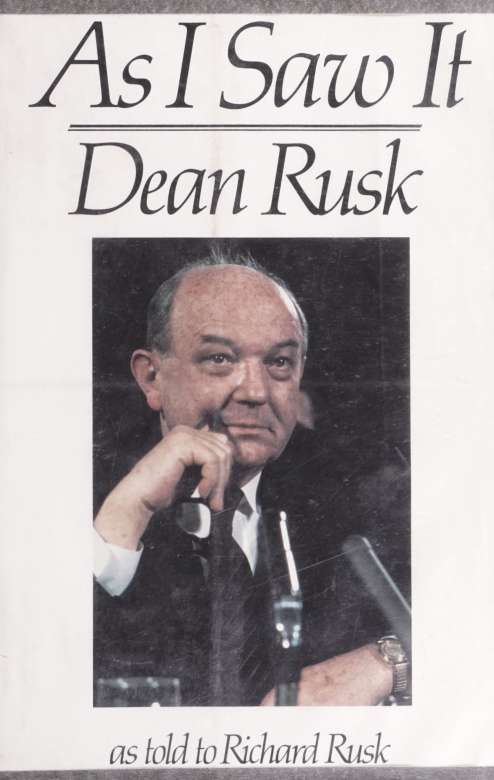

When I joined President Kennedy as his secretary of state in January 1961, I announced that I would never write a memoir. Several reasons lay behind this decision. Among them was my desire to let foreign leaders know that if they wished to talk with me in confidence, they could do so. I would not rush to write a book about our conversations. I was also influenced by a remark attributed to George Marshall: If I were to write memoirs I would owe it to myself as a matter of integrity to tell the full truth. But were I to tell the full truth, I would injure a great many people including myself. So I will leave this to the historians. Also relevant is my view that documents generated in the course of public business belong to the government and not to those temporarily serving in government. When I left the Department of State, I took away only my appointment booksthey are available to anyone in the Kennedy and Johnson presidential librariesand copies of my income tax returns; all else I left in Washington.

In June 1984 our son Richard came home to Georgia after many years in Alaska, years spent, I now realize, attempting to understand and make peace with the events of his youth and of my public service.

DEAN RUSKS PREFACE

He could not do this, could not reforge the broken chain, without me. Thus, together we have explored the memories and have written not a formal memoir or a book based on documents but a human story, father to son.

Our many dozens of taped interviews will be found in the University of Georgia Library. This is as much Richs book as mine. I have shared with Rich my best recollection of what my colleagues and I had in mind about the many issues which arose in the 1960s. If my memory is faulty at times, the responsibility is mine. There are many anecdotes in these pages, and a few I did not myself eyewitness. Even these are a part of the Washington folklore of that period.

Any future historian must sift through the blizzard of paper work that has fallen upon the world in our century. During my eight years in Washington 2,100,000 cables went out of the Department of State over my signature. Of these I personally saw fewer than 1 percent. The extensive documentary record cannot tell the whole story. Documents are surrounded by much discussion among those handling policy, and these discussions are, of course, nowhere in the record. There may be some value in my attempt to reconstruct what was in our minds as we worked through the jungle of events.

A central theme helps sort out the extraordinary complexity of this postwar period. We have now put behind us forty-five years since a nuclear weapon was fired in angerperhaps the most important single development of the postwar years. Our young people should be reminded of these forty-five years as a platform to build upon and a partial antidote to the Doomsday talk with which they are being battered. I recognize my generations shortcomings. We left America an abundance of serious problems. Even so, I wish that those who follow can move into the future with a measure of hope and confidence. Optimism is vital to the workings of a democracy and an operational necessity in the nuclear age. I am profoundly confident about the prospects for avoiding nuclear war.

I am deeply moved by the attitudes and performance of the American people in this postwar period. The Kennedy and Johnson presidencies in particular were years of crisis; there was little of Camelot about them. There have been mistakes and disappointments in these four decades; we have learned some hard lessons. But in the longer view the American people have conducted themselves with responsibility, restraint, and even generosity. Never has so much sheer power been harnessed to the rather simple and decent purposes of the American people. There is nothing for which to be ashamed as we look to the future.

DEAN RUSKS PREFACE

I deeply regret that limitations of space did not permit me to give adequate credit to the talented people with whom I served. This includes the leaders of a professional diplomatic service which is second to none in the world. I mention only a few: Ted Achilles, Tap Bennett, Charles Bohlen, Martin Hillenbrand, Foy Kohler, Alexis Johnson, Carol Laise, Thomas Mann, David Newsome, Joe Sisco, and Llewellyn Thompson.

Some were not members of the Foreign Service: George Ball, Lucius Battle, McGeorge Bundy, William Bundy, Ellsworth Bunker, David Bruce, Abe Chayes, Harlan Cleveland, Adrian Fisher, Arthur Goldberg, Jim Greenfield, Averell Harriman, Philip Jessup, Nick Katzen-bach, Bill Macomber, Robert Manning, Bob McCloskey, John J. McCloy, George McGhee, Len Meeker, Ben Read, Eugene Rostow, Walt Rostow, Tony Solomon, Adlai Stevenson, Phillip Talbot, Barbara Watson, and many others. I was particularly blessed in having secretaries and personal assistants such as Phyllis Bernau Macomber, Jane Mossellem, Andy Steigman, Harry Shlaudeman, and Emory Swank in the State Department and Ann Dunn at the University of Georgia. Surely no secretary of state in this modern period has been surrounded by such talent. A full listing would fill many pages.

Together, Richard and I have worked hard to write about life as it really was. He decided what should be included or left out in a book of this size. I greatly hope readers will profit from reading it as much as he and I have enjoyed making it.

Finally, the Rusks of Cherokee County have found it difficult to talk about things they feel most deeply. I must, however, express my loving appreciation for that talented and gallant lady who has tolerated me for more than fifty yearsVirginia Foisie Rusk. She has combined grace and commitment to the duties which have fallen upon her throughout our livesespecially as the wife of the secretary of state. She has been the same person in the presence of presidents, princes, and potentates as she has been with my country cousins in Georgia. Our three children, David, Richard, and Peggy, and their respective spouses and our six grandchildren have been blessed by her love and dedication.

Foreword

"What was it like to have an American secretary of state for a father?" I've been asked that hundreds of times, and I always answered as offhandedly as possible, with a glib "No big deal" or "It gave me a shot at some girls I never had a chance at otherwise," knowing that people might have had reasons of their own for asking and that a serious answer might be germane to their own experiences. Well, it was a big deal, and twenty years later it became time to answer that question.